Sanchita Islam

This article appears in the book London Fiction, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

Brick Lane in the East End of London has become something of a tourist hot spot, famous for its curry houses, boutiques and heady vibrant mix. Sunday market in particular is a time when all walks of life congregate to enjoy the array of market stalls and street artists and its infectious energy.

Monica Ali’s seminal novel, in spite of its title, is not about Brick Lane itself, and has little to say about the commercialised or hip aspects of the locality. Instead she writes about the Bangladeshi community which now predominates – Brick Lane has a rich migrant heritage dating from the French Huguenots and encompassing the Irish, the Jews and more recently the Bangladeshis, who came to London in the fifties and sixties in search of that elusive ‘better life’ – and hones in on the ghettoised council estates that loom tall like chunky limbs on splinter streets. These often eerily quiet estates are home to thousands of Bangladeshis, primarily from the region of Sylhet – a once poor rural district that has become relatively affluent through remittances from British Bangladeshis. If you visit Sylhet, one of the first things you see driving from the airport into the main town is a massive billboard advertising Taj Stores on Brick Lane – a bizarrely surreal sight and a clear sign that Brick Lane is famous globally as well as locally.

Brick Lane was adapted for the big screen in 2007. Both the book and the film caused controversy. Sections of the Sylheti community were affronted by Ali’s depiction of them as insular, backward, conservative and uneducated. Filming in the Brick Lane area had to be clandestine. Monica Ali’s book met stern disapproval in Bangladesh, but found a readership there all the same. Stuck in a traffic jam in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh and the city of Ali’s birth, I was surprised to see street vendors touting pirated copies of the book, shouting ‘B –rick L-ane’ for everyone to hear as they waved them enthusiastically in the dusty air.

In interviews, Monica Ali has spoken of the fact she has no specific sense of home – something shared by her principal character in Brick Lane, Nazneen, who struggles to adapt to London life. It could be argued that Ali’s lack of grassroots knowledge of the Sylheti community has an impact on the characters’ authenticity. Ali’s parentage is half Bangladeshi and half English. She was brought up in Lancashire and is Oxbridge educated and has no personal links to the Brick Lane area. The book was a bestseller and a hit with the critics earning Ali a place on the shortlist for the Man Booker Prize in 2003, which begs the question of whether she created a story and characters that people wanted to hear and believe.

Monica Ali begins the story with the birth of Nazneen in a Bangladeshi village. The untimely death of her mother pushes Nazneen towards an unconventional path. Set between 1985 and 2002, the narrative focuses on three main characters all living on an imaginary East End council estate. Nazneen is introduced as the submissive, village, virgin bride sent to London to begin a new life with Chanu, her rotund, older, opinionated husband. The third character is Karim, a second-generation streetwise Sylheti ‘lad’ who becomes the ‘lover’ of Nazneen and is swiftly radicalised after 9/11.

The novel has a three-tier structure that maps the evolving landscape of each principal character. Significantly, Chanu is not from Sylhet. He presents himself as a minority within a minority, suggesting his alienation from a community he perceives to be regressive, parochial and overly religious. An aspirational immigrant, Chanu purports to be highly educated and has framed certificates to prove it. He represents the Bangladeshi immigrant who is brimming with optimism about carving a great, solid future, only to have his dreams consistently thwarted. He idealistically talks about creating a ‘mobile’ library, which would ‘bring the great world of literature to this humble estate’ and by doing so would open the eyes of the Sylhetis who seem voluntarily castrated from the rest of the world. He pities those Sylhetis complacent within the parameters of their close knit communities who refuse to learn English and never ‘leave home’, preferring to keep their hearts ‘back there’ and ‘recreating the village here’.

Nazneen listens submissively to her husband’s rants without comment, often whilst cutting his toe nails. Her sphere comprises the dour, brown interior of her small flat, and Chanu is her only connection to the world beyond. Seldom venturing outside, Nazneen endures a claustrophobic, static existence. When Nazneen first entered the world, her parents thought she was stillborn. Nazneen’s soul is in effect moribund, stuck in a dusty box that she now calls home, ‘… the muffled sound of private lives’ inhabiting similar boxes is the only sign of a life outside her own. At night, when she has a chance to dream, she reverts ‘back’ to an idyllic lush Bangladesh where there is light, space, limitless nature and the freedom to roam. She prefers to lose herself in memories and dreams of an earlier life that was so abruptly taken away from her.

Nazneen’s grasp of English is poor and Chanu doesn’t encourage her to learn the language: ‘where’s the need, anyway’. On one occasion she does head out, after hearing distressing news about her sister in Bangladesh, and is left walking ‘in circles’ such is her lack of basic topographical knowledge. It seems that she can only manage ‘bird steps’ and is forever trapped in the small space she inhabits. Without even a rudimentary knowledge of English she can’t ask for help. She’s hit inadvertently by a man with a briefcase that swings ‘like a mallet’, the cold rips through her sari pinching her skin spitefully, and crossing the road is like ‘walking out in the monsoon hoping to dodge the raindrops’. The world is hostile, angry and violent and renders her disorientated, small and feeble.

The TV acts like a portal transporting Nazneen into other worlds. A charming metaphor unfolds as she is mesmerised by the fluid movement of the ice skater, who glides through life unencumbered, in control of her elegant physique and in perfect harmony with her partner. She is derided by her husband for her mispronunciation – ‘ice-eskating’ – and he comments that failure to grasp the language ‘is a common problem for Bengalis’. She clumsily seeks to emulate the ice skater, trying to renegotiate her body in new forms as if trying to rid herself of the shackle that is her room, home and husband. Her efforts end in failure, but this marks a first real attempt to spin, to move, to find a way to be alive again.

Ali builds up the layers of Nazneen’s character, the shock of being in a new country, the trauma of losing her first child, her escapism through dreams of a romanticised childhood homeland, her sister’s letters that represent paper fragments of ‘home’, the meticulous cooking of authentic, tasty Bengali food, her tolerance of Chanu’s garrulous wrangling and her gradual adjustment as a wife and mother. Nazneen is slowly redrawing the faint map of her existence with bolder lines.

In the second part of the novel Monica Ali continues to evoke, stroke-by-stroke, Nazneen’s growing confidence and subtle transformation from submissive, subordinate wife to someone who has begun to find her voice. She now has two daughters and is more settled into life in London. Conversely, it is Chanu, previously confident and full of grandiose plans, who begins to change and retreat. After failing to be promoted, he finds work as a taxi driver out of sheer necessity. He increasingly uses the internet to gain access to a virtual ‘entire world’. Chanu is drifting into an abyss of disillusionment. He is adamant that his daughters only speak Bengali at home and makes them recite the national anthem of Bangladesh. He begins to manifest signs of the ‘going home syndrome’ to which he has previously been so vehemently opposed. Chanu’s displacement is even more evident when he decides to take his family on a day trip to central London, which despite living in England for over thirty years he has never seen. Chanu’s parameters are not much wider than his wife’s. When a passer-by obligingly takes a photo of the family and then asks where they are from, he states: ‘we are from Bangladesh’. His mind is lodged in the space of his much-yearned-for Bangladesh and he feels little sense of being British.

Nazneen, by contrast, is stepping out of the dusty box of her previous existence. Through TV and by conversing with her daughters, she becomes proficient in English and starts working from home. Chanu, perhaps surprisingly, encourages her in this. She begins to sew to earn the much needed money that her husband is failing to provide. He meanwhile is embroiling the family in debt to the local loan shark. Now Nazneen has unwittingly become the head of the family. Her new vocation leads to the introduction of the middleman, British-born Karim, who stammers when he speaks Bengali but ‘in English he found his voice’. Karim is shaped through the idealised perspective of Nazneen, who sees this younger man as a means of finding a much yearned for ‘place in the world’.

Monica Ali quietly documents the harrowing scenes of 9/11 as seen by millions the world over. Chanu is mesmerised, glued to the TV, and his rants have an ominous foreboding of the Islamic extremism that has become pervasive. His wife, Nazneen, is bewildered, such is her detachment from the outside world. It is events like these that begin to dispel the stillness that she previously inhabited.

The introduction of Karim precipitates Nazneen’s sexual awakening. In one pivotal scene she puts on a bright red sari and surreptitiously attends a meeting of the ‘Bengali Tigers’, the activist Islamist organisation headed by Karim, in order to be close to him. This radical group intends to rise up against the Western powers to defend the Muslim world. Karim’s impassioned speeches about the distant war-torn territories of Bosnia, Chechnya and Afghanistan expand her knowledge of the world beyond the flat and the estate. They stir Nazneen’s soul. Ali poignantly describes Nazneen shaving her legs in anticipation of her first major sexual encounter with Karim and an affair ensues in the same stifled interior of the flat. She sees Karim as her ice-skating partner, the antithesis of Chanu who craved her to be still and silent. Karim will, she hopes, help her to ‘skate through life’ and ‘spin, spin, spin’.

In the final section the characters shift further. Chanu surrenders all his dreams and returns to Bangladesh, impecunious, dejected and alone. He prefers the remembered world of ‘home’ in his head, since the Bangladesh of his youth is no more. Karim ends up pursuing ‘jihad in some far away place’. He stammered in English too, we learn, unable ever to articulate clearly in either English or Sylheti. Both men fail to find a place in the world.

Nazneen opts to remain in the flat in London with her children. She has an erstwhile best friend; she learns to stand up for herself by confronting the loan shark; she has found her voice and uses it to protect her family without fear. The story ends with Nazneen on an ice rink, wearing a sari, but fully prepared to move freely on the ice unaided, finding the courage to ‘spin’ on her own, finally conquering the space she inhabits and embracing the freedom she discovers within it.

Ever since Brick Lane was published I have been asked repeatedly about the book, perhaps because I am Bangladeshi and have worked and lived close to Brick Lane. There is certainly much to discuss about Ali’s representation of the Bangladeshi community in east London – the cultural significance of the novel – and about its curious impact on me. Do I relate to the characters Ali portrayed, or are they verging onto generic type? Do I recognise the ‘Brick Lane’ area that the novel tries to portray? Does she evoke a Bangladesh that resonates with me? Is this novel a credible depiction of a very complex people residing in a mercurial London?

Chanu’s character represents a stereotype of the immigrant who is spilling with lofty talk, but fails to make his mark. His fictional antagonism towards the Sylheti community was met by anger among the real residents of the estates in the Brick Lane vicinity. His is a familiar story of discrimination, impoverishment, and shattered dreams. His treatment of Nazneen fits into the patriarchal views that women should be mute, subordinate and stagnant. Nazneen’s feisty daughter depicts a new generation of women who will not follow the paths of their docile mothers. Nazneen’s daughter speaks in a loud, rebellious tongue that was more interesting to me than her mother’s.

Karim’s character, it could be argued, is one that we read about in today’s papers, the angry radicalised Muslim youth who has turned against the West – the potential terrorist in the making, disaffected and lost. He finds Nazneen attractive because she is somehow untainted, unwesternised and therefore pure. His disappearance at the end of the novel is predictable. We know little more though about the psychological make-up of Karim, apart from the outline of his silhouette.

Nazneen inhabits a cultural image of the enfeebled, reticent, uneducated wife trapped in an arranged marriage with an older man living in a poky council flat. Ali shows how Nazneen’s character breaks out of the mould she was initially cast in by not dutifully accompanying her husband to Bangladesh, but rather staying in London to raise her daughters alone, to work, to provide, to step out into the world and explore what it has to offer. Ali’s book is not really about Brick Lane, but about a woman who finds herself trapped in a strait jacketed life in an alien city that is overwhelming. Ali’s story reflects the lives of other women that inhabit similar council blocks, women who remain invisible. The narrative charts Nazneen’s quest for freedom, but ultimately the transformation Ali painstakingly maps is not as profound as I would have hoped. The experience of the story is too claustrophobic; the area of east London in which it is set, the self-titled Brick Lane it alludes to, is not seen or experienced in a way that is evocative or lasting.

Monica Ali only hints at the complexion of Brick Lane without adding the cacophony of smells, people and colour that it is famed for. Perhaps she intended to show how communities become enclosed and dislocated, stuck in a myopic existence of life on the estates. But the result is that the reader doesn’t experience the multi-layered richness of Brick Lane.

The sight of burka clad women walking down side streets, weighed down with their shopping, wearing socks with sandals to protect their toes from the cold; younger teenagers donning hijabs, zooming about in their cars or chattering with friends, confident and cocky; packs of Asian lads with shaved heads dripping in designer gear as they loiter and heckle; or solitary elders walking slowly in traditional dress – these are all strong visual images that are ubiquitous in the Brick Lane area, and noticeably absent from this novel. The Bangladeshi community may stick to their own, but they slide past other locals and have a visible and audible presence. It is a shame that Ali’s story takes place primarily in a flat. We never really get a sense of this ‘presence’ on the streets or beyond the estate. Nor do we understand the distinct geography of Brick Lane and how communities spill into one another simply because of proximity.

Brick Lane is not the definitive novel about Bangladeshis or about the area. There are richer tales to be woven. The novel comes across as inauthentic in its representation of the residents and the local geography. It is as if the estate is suspended in a different east London that is remote and closed off. Perhaps Mile End would have been a less misleading title. Yet Monica Ali succeeds in giving her key character, Nazneen, a subtle and distinct hue. She seeks to tell a story about a community whose voice is seldom heard, and her novel opens the door a little on a closed and secretive world.

About Brick Lane

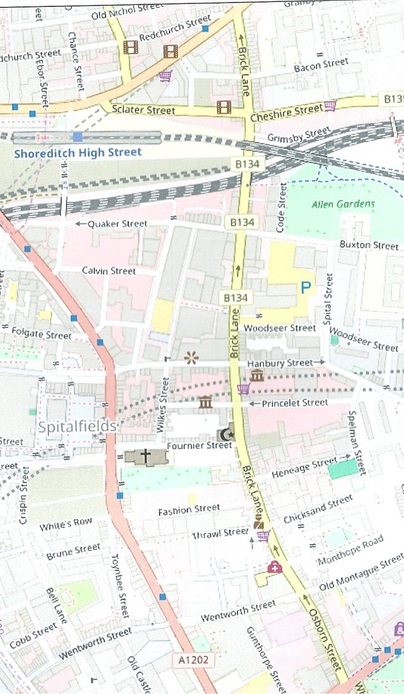

I first came to Brick Lane in 1992 – about the time I became Miss Bengali (my mother entered me in the competition without my knowledge). Brick Lane then seemed a rather non-descript street. I felt intimidated by the place, and unfamiliar with the surroundings which have made the street famous. It’s now feted for its vibrant blend of curry houses and trendy boutiques. And it’s home to the artistic elite of London with residents like Tracey Emin on Fournier Street where French Protestant refugees once lived, the first of successive waves of immigrants to reside in the East End, each leaving its own distinct footprint.

In 1999, starting out tentatively as an artist, I had my first exhibition on Dray Walk, part of the hip Truman Brewery complex (once the largest brewery in London which stopped making beer in 1988). In the last decade the area has undergone rapid change. Spitalfields has been renovated and blends into the affluent gleaming buildings on Liverpool Street on the edges of the City’s ‘Square Mile’. The achingly cool (or not so, it’s a matter of opinion) Shoreditch is only a hop away.

The Truman Brewery let space to musicians and dot-coms alike, expanding its influence with the establishment of the Vibe Bar in the early 90’s to the opening of clubs, an independent record store and more bars and eateries. The complex continues to assert its influence in the realms of art, fashion, design and music. The Brewery neatly slices Brick Lane in two – the section closest to Whitechapel Road is distinctly Bangladeshi in flavour with its restaurants, sari, music and DVD shops and grocery stores selling Bangla food, spices, fish and poultry; the part closest to Bethnal Green Road is lined with boutiques and bars, not forgetting the round-the-clock bagel shops.

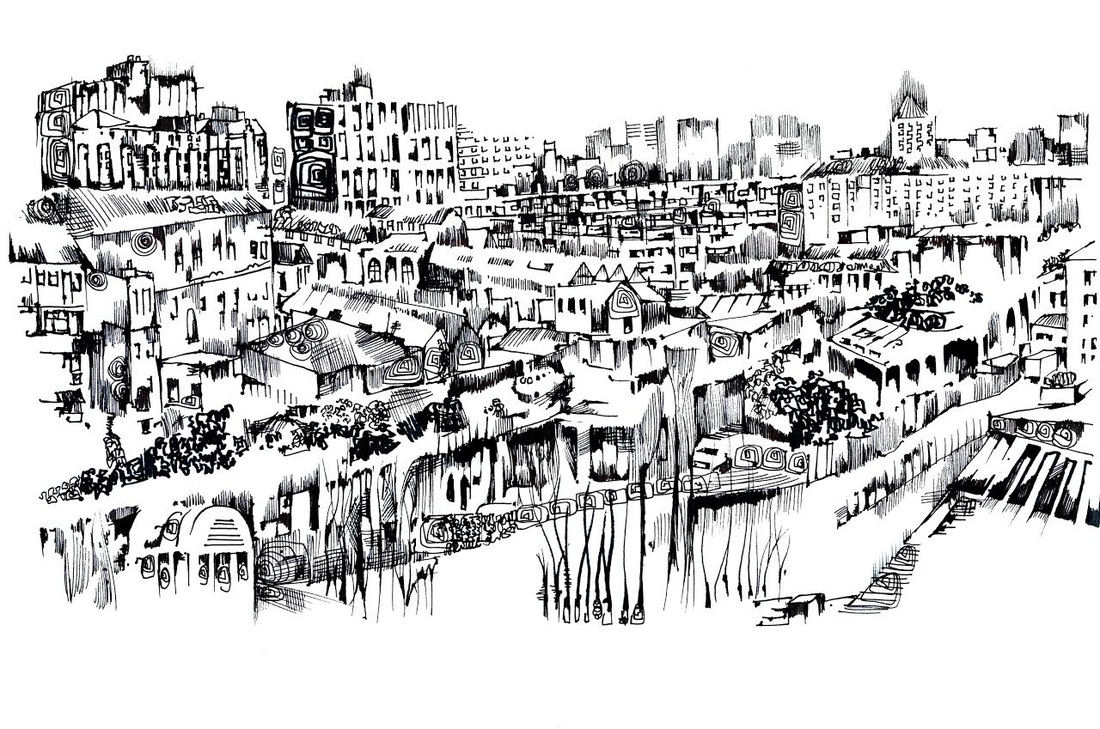

The side streets are dominated either by council blocks or brand new flats that have attracted an influx of professionals. There’s a strong sense of divide between the impoverished immigrant communities and the pockets of more affluent incomers. In an area already home to top end restaurants and cultural centres, Shoreditch House launched on Bethnal Green Road in 2007. It’s not unusual to see paparazzi loitering outside this exclusive private members’ club, which boasts a pool on the top floor. I was artist in residence there for two years until 2009, creating graffiti art on the toilet doors and a thirty foot scroll of the panoramic view of east London.

As I drew, the landscape changed irrevocably before my eyes. I made it my mission to bring people to the club that otherwise wouldn’t have access. But you don’t see many Bangladeshis there, apart from the cab drivers waiting for business in the usually cold, dank night. Derek Cox, a dedicated community worker for the last thirty years, says “Brick Lane is more like Piccadilly Circus on a Saturday night”. It is sometimes not a pleasant place to be at the weekend with drunken revellers stumbling down Brick Lane treading on broken glass and urinating wherever they might fancy. Local residents don’t appreciate this new development.

The new Shoreditch train line was finished in time for the Olympics. It severs the East End like a hideous concrete limb and still the restless change in the area does not cease. The East is constantly evolving and will continue to do so. Tesco has found a footing on Whitechapel Road, Bethnal Green Road and Commercial Road – if a Tesco ever opens on Brick Lane then perhaps it will no longer be deemed ‘cool’. Shops open and close with alarming alacrity, a consequence perhaps of the dire economic climate. It’s sad that community centres have closed down while clubs and bars flourish. Even an old public toilet – opposite the now defunct Christ Church youth centre – has been converted into a club.

Amid the changing times, there remain some fixtures in the East. The newly renovated Whitechapel Art Gallery stands tall and elegant. It’s not uncommon to see the artists Gilbert and George, local residents for decades, popping into the Golden Heart Pub, while a woman with her head covered, laden with shopping, disappears down Hanbury Street. It will be interesting to see how the Somali community, the latest migrant community fleeing from strife in the Horn of Africa, will make its mark on the area. As discussed in my book Avenues, there are already tensions developing between Somalis and the more established Bangladeshi enclaves.

All these strains, these contrasts and incongruous juxtapositions, give Brick Lane a strange allure and make life here that little bit more interesting – visually, culturally and socially.

Sanchita Islam is an artist, writer and film maker. She runs Pigment Explosion, an organisation specialising in international and London-based arts projects. Her books include Gungi Blues, From Briarwood to Barisal to Brick Lane and Schizophrenics Can Be Good Mothers Too.

References and Further Reading

– Burrow, Peepal Tree, 2004

Sanchita Islam (ed) – From Briarwood to Barisal to Brick Lane, 2002

– Avenues, 2007

Rachel Lichtenstein – On Brick Lane, Penguin, 2008

Elisabetta Marino – ‘Intersecting Geographies in Monica Ali’s Brick Lane‘

– ‘An Introduction to British Bangladeshi Literature and to Sanchita Islam’