Lisa Gee

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

Written when its author was twenty-one and published, in 2000, when she was twenty-four, Zadie Smith’s debut novel was an instant critical and popular success. Commentators and readers alike were beguiled by the novel’s exuberance, intelligence and superb prose as well as the way the author captured the spirit of the age. Young, brilliant, beautiful and mixed race, Smith was the perfect image for an optimistic London at the start of a new millennium. The Y2K bug hadn’t caused ATMs to implode as the twentieth century ticked into the twenty-first, Britain was between wars, the Chancellor was predicting an end to boom-bust cycles and stock markets around the world hit all-time highs as the dot.com bubble continued to expand. London was prosperous: a place where people from a variety of backgrounds could mix it up and make it. Londoners might not have been queuing for the Millennium Experience, but we weren’t yet disillusioned with Tony Blair’s government, its rhetoric of social inclusion and the black hole between its principles and its practice. White Teeth is audacious, ambitious, and optimistic: absolutely the right book for its time.

The novel received only one dissenting review: this appeared in a small literary magazine called Butterfly and described the book as ‘the literary equivalent of a hyperactive, ginger-haired tap-dancing 10-year-old’. That review was written by Smith herself.

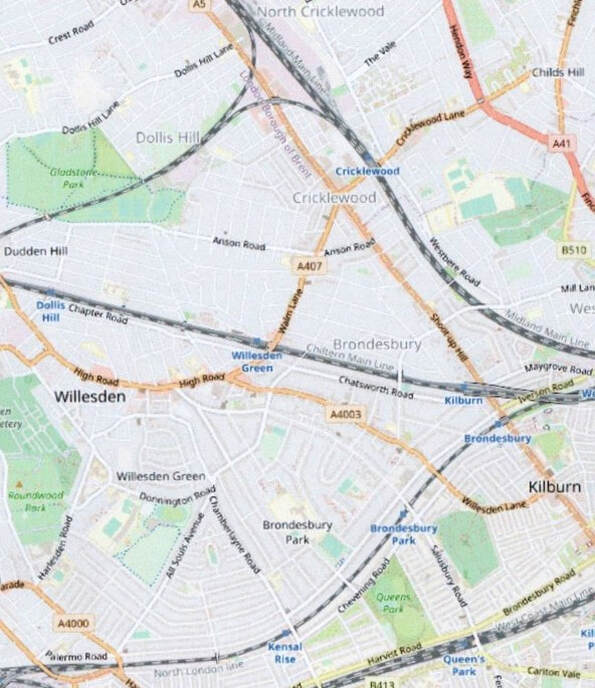

Centring on an unlikely friendship between white, workingclass Archie Jones and Bengali immigrant Samad Iqbal, White Teeth opens with Archie attempting suicide early in the morning on New Year’s Day, 1975. He’s gassing himself, in his car, outside a halal butcher’s shop on Cricklewood Broadway. The owner – Mo Hussain-Ishmael – is not happy, because Archie is parked in his delivery area and he’s expecting a large consignment of meat any minute.

Mo’s explanation to Archie about why he can’t kill himself there sets the tone for all that follows: “We’re not licensed for suicides around here. This place halal. Kosher, understand? If you’re going to die round here, my friend, I’m afraid you’ve got to be bled first.” It’s zippy, irreverent, and, most significantly, mashes up cultures and religions, the sacred and secular in unexpected ways.

Gifted a second try at life by this unlikely saviour, Archie (aged forty-seven) fetches up at the fag-end of a nearby hippy New Year’s Eve party, where he meets nineteen-year-old Clara: tall, black, escaping from a tangled combination of dark basement flat in Lambeth, a Jehovah’s Witness mother and romantic disappointment. They marry within weeks and move to a ‘heavily mortgaged, two-storey house in Willesden Green’: the area where Zadie Smith grew up and learned to tap dance at Adele’s Dance School. Clara reflects that it’s ‘not the promised land – but … nicer than anywhere she had ever been’.

While Archie is kind, long-suffering and passive to the extent that he can only make significant decisions by flipping a coin, his friend Samad, a Bangladeshi Muslim with one arm rendered useless by friendly fire (“A bastard Sikh,” he tells Archie, early in their acquaintance. “As we stood in a trench his gun went off and shot me through the wrist”), is pompous and boastful. Obsessed with his proud Bengali origins and particularly his great grandfather Mangal Pande, who fired the first bullet in the Indian Mutiny/Rebellion of 1857, Samad works as a waiter in a restaurant owned and run by a younger, less intelligent relative in Whitechapel and lives nearby. He’s married, via the traditional arranged route, to the much younger Alsana: a complex and realistic mix of traditional values, modern attitudes, bad language and a fierce left hook. Samad, who had been hoping for an easy, biddable wife, is disappointed in this, as in much else.

After a year in which Alsana has been bent over an old Singer sewing machine, fashioning PVC into clothes for a Soho sex shop – ‘many were the nights Alsana would hold up a piece of clothing she had just made, following the pattern she was given, and wonder what on earth it was’ – she and Samad also move to Willesden Green. Alsana, like Clara, judges the area to be ‘nice’ and, importantly, safer than Whitechapel. Not because people are more liberal, less racist than in East London but because ‘there was just not enough of any one thing to gang up against any other thing and send it running to the cellars while windows were smashed’.

Samad and Archie’s wives soon fall pregnant, Alsana with twin boys, Magid and Millat, Clara with a girl, Irie. Alsana and Clara, tentatively at first, become friends and then spend increasing amounts of time together, going to the cinema until they get too pregnant and then meeting Alsana’s lesbian, tell-it-like-it-is ‘niece-of-shame’Neena for lunch in Kilburn Park (aka Kilburn Grange).

It’s during one of these get-togethers that recent history bursts into the present. As, in her opinion, men have caused most – if not all – the trouble in the world, Neena isn’t impressed that Alsana is pregnant with boys. Feeling responsible for jolting her and Clara out of their false consciousness, she says if it was her, she would consider abortion. Alsana is shocked to the point of choking on her lunch, Clara finds Neena’s comment ‘hysterically funny’. Sol Jozefowicz, the elderly former park keeper still policing the park despite his job having ‘long since having been swept away in council cuts’, comes over to check if they’re all right. Alsana, explaining what’s happened and, complaining about Clara’s response, asks:

“The murder of innocents – is this funny?”

“Not in my experience, Mrs Iqbal, no”, says Sol Jozefowicz … It strikes all three women – the way history will, embarrassingly, without warning, like a blush – what the ex-park keeper’s experience might have been.

The difficulties with history, together with the devotion to tradition – something the book’s narrator fingers as even more corrosive, more dangerous than religion – intrude throughout White Teeth like the 1950s council blocks that occupy bombholes in Harlesden’s Edwardian terraces. The past, and people’s relationship with it, is, one way or another, always a problem: ‘immigrants’, we are told, ‘cannot escape their history any more than you yourself can lose your shadow’. And, ‘In Archie’s experience anything with a long memory holds a grievance’.

But then, despite the fizzing optimism of the book’s tone – and it’s the way the story’s told, rather than the story per se that sets the upbeat tone – the future ain’t easy either. Every prediction made, or followed, by the book’s protagonists, every attempt at influencing the outcome of events – major or minor – turns out wrong. The twin impossibilities of controlling and foreseeing the future and escaping the past thread through the novel like cyclists avoiding traffic. And while, on the one hand, this powerlessness is frustrating for the characters who’ve made or followed a prediction, or acted in ways intended to produce specific, desired results, on the other, it’s rather reassuring. No one individual or group has the capability to either predict or control anyone else’s future.

During the BBC Radio 4 ‘Book Club’ devoted to White Teeth, Zadie Smith described Willesden Green as an ‘extremely successful’ example of how people of different ethnicities and beliefs can live, work and study together. She spoke about how kids of every race would walk to school (she attended Hampstead School in Cricklewood), grow together and go to each other’s parties. In the novel, the Iqbal and Jones children do much the same thing. They go to the same schools and hang out together in a similar time and place. Like Irie Jones, lots of the kids have first names from one country or culture and last names from another. This isn’t always because their parents were born into two different cultures: some people’s mums simply give them a name they liked from someone else’s.

Having transposed her own experience into the novel, Smith later described this melting pot vision as naïve. She was, she felt, right to show that people don’t give up their own gods easily, wrong in assuming that living cheek by jowl with each other would inevitably overcome fundamentalism and parochialism. It doesn’t in real life, even in a place as happily mixed as Willesden Green. But, to be fair, it doesn’t in White Teeth, either.

Clara’s mother, Hortense, clings on to her faith even after the end of the world fails to materialise on the date the Jehovah’s Witness leaders predicted (again). Meanwhile, at primary school governors’ meetings, Samad embarrasses Alsana by campaigning for the Harvest Festival to be struck from the school calendar. In his opinion, the nine Muslim festivals are squeezed out by the thirty-seven Christian ones. If, Samad suggests, they dispensed with the ones that aren’t properly Christian – like the pagan Harvest Festival – there would be time to celebrate the proper Muslim ones.

“Where in the bible does it say, For thou must steal foodstuffs from thy parents’ cupboards and bring them into school assembly, and thou shalt force thy mother to bake a loaf of bread in the shape of a fish? These are pagan ideals! Tell me, where does it say, Thou shalt take a box of frozen fishfingers to an aged crone who lives in Wembley?”

That typically irreverent mix of symbolic fish and everyday fishfingers grounds the novel more firmly in London than Smith’s light-touch descriptions and namechecking of the novel’s main locations: Willesden Green; Cricklewood; Kilburn; Finchley Road; Harlesden Jubilee Clock; its occasional forays into Lambeth and central London and its trips to the local parks – Gladstone Park, Kilburn Grange Park, Queen’s Park and Roundwood Park (these parks with their cafés and playgrounds are important community hubs). In fact – especially once the focus of action shifts to the younger generation – place itself is something taken largely for granted. Only Alsana truly appreciates its significance. Conversely, born into a temperate climate and living on land that tends to remain stable under their feet, ‘the English have a basic inability to conceive of disaster’. This statement is illustrated, neatly, a few pages on, with weatherman Michael Fish’s infamously wrong 15thOctober 1987 there-won’t-be-a-hurricane-tonight prediction.

Alsana is brooding about place because Samad, disturbed by the way his sons are influenced by their environment, has, without consulting her, sent Magid – the better behaved, brighter twin – off to Bangladesh. There, he believes, at least one of his sons (he couldn’t afford to send both of them) will receive a proper traditional upbringing and return the man Samad wants him to become. And yet Samad finds not being in control harder to live with than any other character. He can’t cope with being unable to control his own desires, his wife or his sons, their choices and their futures.

Sense of place and people’s relationships to it are, inevitably, different in an environment that is – under normal circumstances – structurally safe. And, though it’s an obvious point to make, White Teeth makes clear how, through the twins’ separation, it’s also inextricably bound up with people’s relationships with each other. If human beings can be compared to plants, most of us are more akin to those with aerial roots than we are to trees. Our roots grow laterally into family and friends, through time and space into cultures, traditions and religions as well as (or sometimes instead of) down into the earth.

Sense of place and people’s relationships to it vary across Smith’s novels, too. In her second, The Autograph Man, one of the themes is the power and value of names. So, although we get to visit the Royal Albert Hall at the outset, many of the London locations in this later novel are, as Adam Mars-Jones points out in his review of the book in The Observer, deliberatelyanonymised. Places are alluded to or described rather than named, and the novel’s main protagonist, Alex-Li Tandem, lives in a fictitious northern London suburb called Mountjoy. Smith’s third novel, On Beauty, returns us to Willesden Green, Cricklewood and the surrounding area, but this time viewed through the eyes of young American visitors, rather than natives. For one – Zora – everywhere apart from Hampstead is ‘crappy’. Meanwhile, her brother Jerome romanticises the area, finding it wonderfully mixed compared to ‘back home’.

Alsana is, predictably, furious with Samad. She calibrates her revenge precisely to hit the exact frequency that will drive her husband to distraction and refuses, from that moment, to answer any of his questions directly. Meanwhile, as if to compensate for his relative safety, Millat’s behavior becomes increasingly risky. He gets into fistfights, drinks, smokes cigarettes and marijuana. He enjoys unprotected, promiscuous sex with a string of willing white, middle-class girls to whom his combination of good looks and self-destructive behaviour prove irresistibly attractive. He immerses himself in all the glorious, easilyaccessible sins London has to offer, before converting to a fundamentalist brand of Islam. His father torments himself with the thought that he’s sent the wrong son to Bangladesh.

Samad finds refuge in his evenings with Archie at O’Connell’s Pool House on the Finchley Road. Run by Abdul-Mickey (to teach them humility, all the boys in his family are called Abdul with an English name appended for practical purposes), O’Connell’s is ‘neither Irish nor a pool house’. It’s a greasy spoon-style caff-cum-gambling den, sans pork products, where you can either play for money, or, if it’s against your religion, just play. It’s the book’s most stable environment: a place of regulars, all men, who can be relied upon, year in, year out, to do the same things and behave in the same way.

When the novel reaches 1990, a family who’d appeared as bit-part players in Smith’s Harvest Festival scene supporting Samad’s motion, shift centre-stage. Living just a couple of roads away from the Iqbals and Joneses, the Chalfens are more Hampstead than Willesden. Celeb gardening matriarch Joyce (who will, later, discover how little human beings are like plants), her husband, the ultra-rational Jewish scientist Marcus and their four sons: Joshua (a contemporary of Irie, Magid and Millat), Benjamin, Jack and Oscar are – with the exception of the deliciously contrary six-year-old Oscar, who is, at one point, observed by Irie ‘creating an ouroboros from a big pink elephant by stuffing the trunk up its own rear end’ – White Teeth’s least successful characters. This is for two reasons. Firstly, unlike the other protagonists, the Chalfens are caricatures. They are twodimensional, chattering-class smugsters; self-congratulatory in the extreme and lacking in awareness to a comic, but unrealistic, extent. Secondly, as Irie notes, scanning the thing on the wall in Marcus’s study, they have a family tree that stretches way back: ‘Dates of birth and death were concrete’. The Chalfens, in contrast to Irie’s mixed-up antecedents, ‘actually knew who they were in 1675’.

Whilst this could be true of Joyce’s family, Marcus’s ancestors were, we’ve just been informed, Polish/German immigrants; original name Chalfenovsky. It’s highly unlikely that Marcus would have been able to trace his lineage back further than the few generations his family had been in England or Germany.

Irie falls in love with the Chalfens, their confidence, free-flowing conversation, apparent openness (they are all in perpetual therapy). She misreads their self-satisfaction for a general air of fulfillment: a blatant contrast with her home environment. Zadie Smith has said that she hated the process of writing Irie but later came to think that her character displays some of the novel’s most natural writing.

It’s true. Whereas the Chalfens are transparent caricature and Millat and Magid are, for conceptual neatness, shoehorned into bad/a bit dim and good/highly intelligent roles, Irie is free to grow up, do okay and fuck up like any normal urban teenager. She endures some fairly standard teenage female self-inflicted miseries: unrequited love; a bad hairdressing experience; the inability to see her own beauty; underestimating her own intelligence, but gets through her mistakes and sometimes learns something from them. She’s alternately tongue-tied and mouthy. En route to the novel’s somewhat unsatisfactory and contrived conclusion, she has a superb outburst on the packed number 98 bus she’s riding from Willesden Lane to Trafalgar Square with her parents, Samad, Alsana and Neena. She shouts at the rest of her party to ‘shut the fuck up’, then delivers an extended, high-volume monologue about how lovely and quiet other families are.

Smith is, she’s said, unsure where her debut novel’s title sprang from. Her mother, a psychiatrist, has suggested it’s a subconscious reference to the joke about how you spot black people in the dark. The joke appears in a darkened form in White Teeth, when Irie, together with Magid and Millat – in defiance of Samad – take their Harvest Festival fare to elderly Mr Hamilton in Kensal Rise. This harmless, elderly gent turns down all their Harvest offerings because they’re too hard. His teeth aren’t up to anything that hasn’t first been pulverized. But he still invites the children to stay for tea. He reminds them how important their teeth are, before offering them more sugar and describing how, when he was fighting in the Congo, “the only way I could identify a nigger was by the whiteness of his teeth. … They died because of it, you see? … Biscuit?”

Lisa Gee is a writer, researcher and editor, currently spread thinly across the past, present and future…

White Teeth, Green Spaces

The main locations for White Teeth aren’t at the top of most London tourists’must-see list. But to experience the novel’s Willesden-Harlesden-Kilburn settings it’s worth spending a sunny Sunday touring the parks its characters frequent. All four will be crammed with people of all ages, from a variety of cultures, speaking any number of languages. There will be ball games, frisbees, shrieking children speeding round on/falling off bikes and scooters,earnest joggers with headphones and water bottles, gossiping parents pushing babies in buggies and older people relaxing on park benches, eating ice cream, watching.

If you live round here, it’s nigh-on impossible to make your way through any one of them without bumping into someone you know, being enticed into an impromptu African drumming or Zumba session and/or striking up a conversation with a complete stranger and their surprisingly friendly dog.The parks vary slightly in character as do their demographics: the thirty acre Queen’s Park, as Alsana notes, is the poshest of the bunch. It’s also your best bet if you’re into celebrity spotting. Its café sells Harlesden-made Disotto’s ice cream– as, naturally, does the Roundwood Park one (which also sells local brand LICKALIX). Queen’s Park also has tennis courts, a putting range, petanque pitch, a bandstand and a children’s playground with a paddling pool and a humungous sandpit that’s almost invariably full of toddlers.

Gladstone Park, situated between Willesden and Dollis Hill and named after the Victorian Prime Minister who used to hang out there when it was private property, is the biggest of the four, has the most suburban vibe and also the steepest hill. It features tennis courts, a walled garden, and a delightfully peaceful and secluded café. This contrasts markedly with the Queens Park and Roundwood Parks caffs, both of which are usually packed with children expressing their urgent need for chips at high volume. The annual Gladstonbury Festival isn’t quite as much like Glastonbury Festival as its name might imply.

This contrasts markedly with the Queens Park and Roundwood Parks caffs, both of which are usually packed with children expressing their urgent need for chips at high volume. The annual Gladstonbury Festival isn’t quite as much like Glastonbury Festival as its name might imply.

Kilburn Grange Park is on the eastern side of Kilburn High Road, almost directly opposite the fabulous Tricycle Theatre (since 2018 the Kiln Theatre), with its unimaginably comfortable cinema. At eight acres, it’s the smallest of the parks, but has a lovely rose garden, loads of benches – so even when it’s heaving, you can be lucky enough to find somewhere to sit – tennis courts and a floodlit games area with changing rooms. It also has a fabulous adventure playground and activity centre that opened in May 2010 and formed the prototype for another twenty playgrounds across the capital city. No café, but there are loads just outside on the High Road.

Roundwood Park, which connects Harlesden and Willesden, is the least sports-oriented of the bunch, although it does boast a well-used football/basketball pitch and a beautifully-maintained bowling green that’s protected by a wall of the perfect length and height to walk along if you’re between two and five years old. It has a colourful, if undemanding, children’s playground, a small wooden adventure a slightly more demanding outdoor gym, a small aviary, the inhabitants of which are rather overshadowed by the noisy green parakeets, and a disused outdoor theatre.

References and Further Reading

The Londonist on White Teeth locations:

http://londonist.com/2010/09/london_literary_locations_white_tee.php?showpage=1#gallery-1

Wikipedia on Willesden:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willesden

Rose Rouse’s Harlesden blog: http://roserouse.wordpress.com/

Adam Mars-Jones reviews The Autograph Man: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2002/sep/08/fiction.zadiesmith

Adele’s Dance School: http://www.adelesdanceschool.com/

All rights to the text remain with the author.