Susie Thomas

A version of this article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

My name is Karim Amir, and I am an Englishman born and bred, almost. I am often considered to be a funny kind of Englishman, a new breed as it were, having emerged from two old histories. But I don’t care – Englishman I am (though not proud of it), from the South London suburbs and going somewhere.

In the opening paragraph of Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia, the seventeen-year-old narrator feels compelled to announce his nationality three times. At first, Karim is semi-apologetic (he’s almost English) but by the third declaration he is defiantly not proud of it. No other English novel begins this way. It is set in the 1970s, when the fact that Karim has an English mother and an Indian father means that he is constantly asked where he is from, as if his very existence required some kind of explanation. He is not English enough (too brown) for some, nor Indian enough (he’s never been there) for others.

In 1990 there were hardly any English novels about growing up as a mixed race child so The Buddha of Suburbia and Kureishi’s first film with Stephen Frears, My Beautiful Laundrette, were important interventions in the debate about what it means to be British in the wake of postwar immigration. A lot of critical attention has quite rightly been paid to this. Now, in large part because of Kureishi’s work, multiculturalism is mainstream. So this is a particularly a good moment to look back at less discussed but equally significant aspect of The Buddha of Suburbia: its treatment of class and the links between class and place.

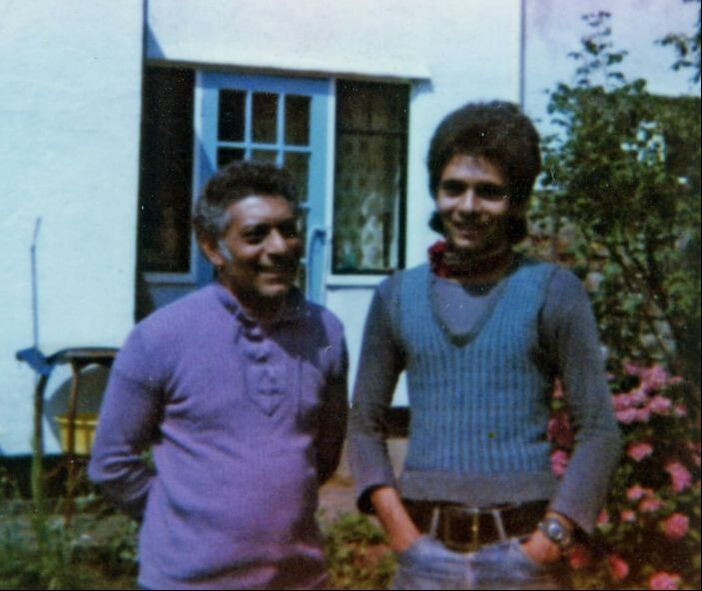

London’s unglamorous suburbs have attracted much less literary attention than the city proper, and it is rare for a novel to flaunt its suburban origins in the title. Kureishi, like Karim, was born in Bromley in 1954. His father, who came from an aristocratic Indian family, was employed by the Pakistani Embassy in London; while his white English mother worked in a shoe shop.

The young Kureishi moved to west London to study philosophy at King’s College and had his first plays performed at the Royal Court theatre in Sloane Square. He has lived on the same page of the A-Z all his adult life and, with the exception of the Bradford setting of his film My Son the Fanatic, all his films and novels have been inspired by the city. The Buddha of Suburbia zigzags north and south of the river, from periphery to core of the city, as Karim tries to find himself: no locality turns out to be quite what either he, or the reader, expects.

From Bromley to Barons Court

The opening paragraph announces not only that Karim has emerged ‘from two old histories’ but also that he is from the ‘South London suburbs and going somewhere’. The journey from a boy’s bedroom in Bromley to ‘the centre of this old city’ charts his struggle to ‘locate [himself]’ as a new breed of Englishman, but Karim is also navigating his way around the class system. Each locality in the novel is precisely depicted in terms of class markers: Karim is desperate to escape suburban stagnation but sceptical of pretentious social climbing, hierarchies and authoritarianism.

The Buddha of Suburbia is divided into two parts: In the Suburbs and In the City. It seems at first as if the novel is straightforwardly linear. Karim progresses from the margins to the centre and from the suburban lower middle class (with a future as a clerk or car mechanic) to the growing metropolitan middle class (working in the theatre, media or academia). Moreover, at least superficially, the novel seems to uphold the conventional opposition between ‘suburbia’ and the ‘city’: Bromley epitomises philistinism while London is the cultural capital.

The suburbs which give the book part of its title are ‘a leaving place’ while the city is ‘bottomless in its temptations’. On the eve of his departure from Bromley, at the end of part one, Karim fantasises about London and what he will do there. Although it is only twenty miles away, it is another world entirely:

There was a sound that London had. … There were kids dressed in velvet cloaks who lived free lives: there were thousands of black people everywhere, so I wouldn’t feel exposed; there were bookshops with racks of magazines printed without capital letters or the bourgeois disturbance of full stops; there were shops selling all the records you could desire; there were parties where boys and girls you didn’t know took you upstairs and fucked you; there were all the drugs you could use. You see, I didn’t ask much of life; this was the extent of my longing.

The city represents freedom and anonymity: more, 1970s London is breathlessly anticipated as a countercultural cornucopia. It is the absolute antithesis of suburbia most significantly, perhaps, in terms of racism. Moving to London means an end to the painful sense of exposure which Karim suffers in the mainly white suburbs and a new safety in numbers. Unlike many coming-to-London novels, the city isn’t a disappointment: ‘So this was London at last, and nothing gave me more pleasure than strolling around my new possession all day’. But within the novel’s basic framework of suburban dullness and bigotry versus metropolitan, multicultural playground, there is considerably more complexity.

The Maddening Suburbs

Kureishi’s suburbs are frequently weirder and madder than we might expect. Partly because it is set against the background of suburban uniformity, Haroon’s transformation from civil servant and commuter into yoga teacher and Eastern mystic, takes on a surreal quality. As he sneaks out of his respectable semi-detached, wearing a red and gold waistcoat and pyjamas concealed beneath his overcoat, he announces proudly: ‘They are looking forward to me all over Orpington’, delighted for the first time to be listened to with respect.

The South London suburbs are portrayed as anything but a homogeneous mass of semis. On the contrary, Karim calibrates the social status and gradations of culture in each neighbourhood meticulously. His family inhabits a respectable lower middle class area, which his step-mother, Eva calls ‘the higher depths’. Setting off from the cul-de-sac which is Victoria Road, Karim and his friends Jamila and Helen walk to the pub: ‘Past turdy parks, past the Victorian school with outside toilets, past the numerous bomb sites which were our true playgrounds and sexual schools, and past the neat gardens and scores of front rooms containing familiar strangers and televisions shining like dying lights.’ Bromley combines degraded public spaces with a philistine display of private status.

There is nothing in Bromley to make Karim want to stay even though he has no clear idea how he is going to get out. His first step on the road to London is Beckenham, which is upper class by Victoria Road standards. When they arrive at Eva’s house, Karim, sounding like a budding estate agent, notes that it had ‘a little drive and a garage and a car. Their place stood on its own in a tree-lined road just off Beckenham High Street. It also had bay windows, an attic, a greenhouse, three bedrooms and central heating’. It’s not (only) the display of money that impresses Karim, rather he’s seduced by the combination of sensuality and intellectualism. But, despite the bidet and the bamboo scrolls, the talk of ‘music and books, of names like Dvorak, Krishnamurti and Eclectic’, Beckenham typifies only a pretentious simulation of culture.

Beckenham represents a premonition of what is on offer in the city and proof that there’s more to the suburbs than DIY and conformity. According to Karim it may be populated by advertising executives at best but suburbia has also been the incubator of genuine musical talent. Ray Davies, David Gilmour, Roger Daltrey are all suburban boys and David Bowie, Bromley’s most famous son after H. G. Wells, is worshipped by the kids in The Buddha. The novel nods in approval of suburban English pop when Karim persuades his father to stop for a pint at the Three Tuns in Beckenham, where Bowie’s career began. It’s full of boys wearing ‘cataracts of velvet and satin, and bright colours; some were in bedspreads and curtains’.

Biding his time until he can get to London, Karim sizes up Chislehurst, the venue for Haroon’s second guru gig: ‘The houses […] had greenhouses, grand oaks and sprinklers on the lawn; men came in to do the gardens’. But this is a detour which gets him no nearer to London than Bromley. Closer geographically to the centre but way down the class ladder is Penge, where Karim’s best friend Jamila lives with her parents above a grotty corner shop called Paradise Stores:

Biding his time until he can get to London, Karim sizes up Chislehurst, the venue for Haroon’s second guru gig: ‘The houses […] had greenhouses, grand oaks and sprinklers on the lawn; men came in to do the gardens’. But this is a detour which gets him no nearer to London than Bromley. Closer geographically to the centre but way down the class ladder is Penge, where Karim’s best friend Jamila lives with her parents above a grotty corner shop called Paradise Stores:

The area … was closer to London than our suburbs, and far poorer. It was full of neo-fascist groups, thugs who had their own pubs and clubs and shops. On Saturdays they’d be out in the High Street selling their newspapers and pamphlets. They also operated outside the schools and colleges and football grounds, like Millwall and Crystal Palace. At night they roamed the streets, beating Asians and shoving shit and burning rags through their letter-boxes.

As the pigs’ heads fly through the shop window and Jamila’s father is racially harassed in the street, her family live with a fear of violence that Karim does not have to deal with on a daily basis in Bromley. South London is a shit-hole of poverty and racism; the streets are more dangerous than in the suburbs and domestic life is equally miserable.

North of the River

Guided by his step-mother, Eva, Karim eventually gets to smart, central London. The initial setting is West Kensington: nearest tube, Barons Court. The author describes the area as caught between ‘expensive Kensington, where rich ladies shopped’ and Earls Court. Typically, it’s the latter that attracts Karim’s attention, an area full of ‘small hotels smelling of spunk and disinfectant, Australian travel agents, all-night shops run by dwarfish Bengalis, leather bars with fat moustached queens exchanging secret signals outside, and roaming strangers with no money and searching eyes’.

Although West Kensington is made up of ‘rows of peeling stucco houses broken up into bed-sits’ what matters to Karim is that it is on the cultural map:

Unlike the suburbs, where no-one of note – except H. G. Wells – had lived, here you couldn’t get away from VIPs. Gandhi himself had once had a room in West Kensington, and the notorious landlord Rachman kept a flat for the young Mandy Rice-Davies in the next street; Christine Keeler came for tea. IRA bombers stayed in tiny rooms and met in Hammersmith pubs, singing ‘Arms for the IRA’ at closing time. Mesrine had had a room by the tube station.

What more could you ask from your neighbourhood? Just as Karim assesses suburbanites according to their driveway, greenhouse, and the contents of their bathroom and bookshelves, so he values Londoners in relation to their ‘cultural capital’ and their post code.

He is thrilled to be offered a job in a radical theatre company in Chelsea, where he meets the beautiful, upper-class Eleanor. He is drawn like a magnet to her flat in Ladbroke Grove:

An area that was slowly being reconstituted by the rich, but where Rasta dope dealers still hung around outside the pubs; inside, they chopped up the hash on the table with their knives. There were also many punks around now … And there were the kids who were researchers and editors and the like: they’d been at Oxford together and they swooped up to wine bars in bright little red and blue Italian cars, afraid they would be broken into by black kids, but too politically polite to acknowledge this.

Eleanor’s set, ‘with their combination of class, culture and money,’ represent the ‘apogee’ of Karim’s ‘social rise’, a ‘cocktail’ that intoxicates Karim’s soul.

Karim wants to be accepted and approved of by London’s bohemian aristocracy, and he is ecstatic to be invited to St John’s Wood: ‘Sensational, I thought … We’d changed at Piccadilly and were heading north-west, to Brainyville, London, a place as remote to me as Marseilles. What reason had I to go to St. John’s Wood before?’ But Brainyville turns out not to be quite the cultural jackpot that Karim had anticipated. His dream of clever people, artistic fame and hedonism in London is undermined by an awareness of how phoney the rich can be, even the really cultured rich.

The bohemian elite trample all over Karim’s dream of London, he is not sure where to go next. Part of him simply wants to crawl home and lick his wounds but he doesn’t know where home is anymore.

Passion Was at a Premium in South London

At various crucial moments in the novel, the forward march of progress from the suburbs to the city is interrupted by a sudden swerve towards South London. This is not simply a reaction against the hollow men and women of the arty metropolis, but because it represents a genuine alternative. After Brainyville, Karim is tempted to move to Brixton, where Terry and his ‘socialist workers’ are squatting and planning the revolution. He gets more involved with Jamila’s activist commune in Peckham.

The fact that the novel is divided into two parts might suggest that there are only two terms up for grabs. But there is a third value and locality: neither suburbs nor city but urban south London; Jamila’s subversive in-between space. Jamila is clearly the political heroine of the novel. An anti-racist march that she organises is the most important event in the book – even though Karim misses it. If his story is not simply a postcolonial snob’s progress this is largely because of Jamila in South London. It’s no wonder, then, that with his lucrative but trashy role in a soap opera at the end of the novel, Karim both celebrates his journey to the centre and knows everything is still a mess.

The Buddha of Suburbia was going to be called The Streets of My Heart, a title which emphasizes the fact that the novel is, on one level, a sentimental education as Karim struggles to ‘learn what the heart is’. The first title also suggests that this is an urban novel in which the streets, instead of being a place of danger as so often in London literature, are the locus of erotic possibility.

The Buddha of Suburbia was going to be called The Streets of My Heart, a title which emphasizes the fact that the novel is, on one level, a sentimental education as Karim struggles to ‘learn what the heart is’. The first title also suggests that this is an urban novel in which the streets, instead of being a place of danger as so often in London literature, are the locus of erotic possibility.

In some ways, The Streets of My Heart might seem to reflect the contents of the novel more accurately. After all, only the first part of the novel is actually set in the suburbs; and Karim’s father, the eponymous Buddha, fades from view for much of the second part. Despite this, the title The Buddha of Suburbia is not only more catchy and original but also emphasizes the heterogeneity of the novel’s suburbs, which are not all steely conformity and twitching net curtains. ‘Was I conceived like this,’ Karim wonders, ‘in the suburban night air, to the wailing of Christian curses from the mouth of a renegade Muslim masquerading as a Buddhist?’

Even though Karim can’t wait to get away from them, Kureishi transformed the traditional view of London’s suburbs, making them a far more interesting place.

Susie Thomas edited A Reader’s Guide to Hanif Kureishi (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)

Down on My Knees in Suburbia

Walking around Bromley today, the architecture does not seem to have changed dramatically in the years since The Buddha of Suburbia was published. The area feels more spruced up than in the pages of the novel; the bomb sites are long gone and the parks are well kept. The defining difference between Bromley in the 1970s and now has less to do with bricks and mortar than racism.

‘Down on my knees in suburbia / Down on myself in every way’ – Bowie’s haunting soundtrack to the film adaptation of Kureishi’s novel, made for the BBC in 1993, accompanies Karim (played by Naveen Andrews) as he whizzes along the streets of Beckenham, Chislehurst and Penge on his bicycle. Bromley could be seen as a crucible for the sometimes bloody revolution in attitudes to Englishness that has been wrought in the suburbs. England’s post-war history of immigration is often referred to in the binary terms of ethnically diverse city and monocultural countryside; very little attention is paid to the suburbs, where most people live.

‘Down on my knees in suburbia / Down on myself in every way’ – Bowie’s haunting soundtrack to the film adaptation of Kureishi’s novel, made for the BBC in 1993, accompanies Karim (played by Naveen Andrews) as he whizzes along the streets of Beckenham, Chislehurst and Penge on his bicycle. Bromley could be seen as a crucible for the sometimes bloody revolution in attitudes to Englishness that has been wrought in the suburbs. England’s post-war history of immigration is often referred to in the binary terms of ethnically diverse city and monocultural countryside; very little attention is paid to the suburbs, where most people live.

In a key early scene in the novel, Karim visits Helen, a girl from his school, and is brutally dismissed by her father as ‘a wog’ and ‘little coon’, before being set on by a Great Dane. Typically, Karim tries to laugh off the humiliation by saying the dog was in love with him: its quick movements against his arse told him so. But later in the novel he admits that the racist insults made by Hairy Back (as he dubs Helen’s father) made him ‘nauseous with anger and humiliation’. There is no ‘whining about being spat on at school’ in The Buddha and the routine racism in the suburbs is contemptuously shrugged off for the most part. Nonetheless, when Karim returns to Bromley, his sense of oppression is palpable. The first person he sees is Hairy Back: ‘How could he stand there so innocently when he’d abused me? … I knew it did me good to be reminded how much I loathed the suburbs, and that I had to continue my journey into London and a new life, ensuring I got away from people and streets like this’.

In his landmark essay, ‘The Rainbow Sign’ (1986), Kureishi removed the comic mask in order to describe his childhood in Bromley with his white English mother and his Pakistani father: ‘From the start I tried to deny my Pakistani self. I was ashamed. It was a curse and I wanted to be rid of it. I wanted to be like everybody else. I read with understanding a story in a newspaper about a black boy who, when he noticed that burnt skin turned white, jumped into a bath of boiling water’. This shame and denial were compounded by the absence of any vocabulary with which to resist the racist culture of demeaning subordination and stigmatisation. Nothing was said: nobody in the family seemed to talk about what happened to them outside the house when they came home.

In 2012 I had lunch at an Indian restaurant in Bromley with Kureishi’s sister, Yasmin, and his late mother, who was then still living in the semi-detached house in a quiet cul-de-sac which was the fictional model for Karim’s home. His sister said that as a teenager she loathed going out in Bromley and was glad to have got away to boarding school. His mother still seemed pained and incredulous at the very idea of colour prejudice and insisted that she knew nothing about the racist abuse her son had suffered until she read about it in The Buddha of Suburbia: it was a shock. If she had known he was being spat on at school, she insisted, she would have complained. The mother’s ignorance seemed to exasperate her daughter: either because she didn’t believe her mother hadn’t known, or because she felt Mrs Kureishi should have known better.

When I asked Yasmin about her father she seemed to think that his charisma allowed him ‘to transcend racism’. Although the one thing that all the family seem to agree on is that Shanoo Kureishi loved his home in the suburbs, Yasmin’s belief that he was untouched by racism seemed to mirror her mother’s wishful thinking. Yasmin said that she had known about what happened to her brother alright because ‘he took it out’ on her.

As I walked back to the house, away from her daughter’s watchful gaze, Mrs Kureishi said that when her son was about five years old he had come home upset, asking why he had been called a nigger. I wondered what she had found to say and she replied, sadly, that she just hadn’t known how to respond. As a teenager in his bedroom in Bromley, Kureishi began his first novel, ‘Run Hard Black Man’: he had to find his own answers through writing. His father couldn’t help him find the way; although in The Buddha of Suburbia they have a good time trying:

Growing up in Bromley today would certainly be very different from forty years ago when the novel was set. Crucially, the area is now casually multicultural and groups of school kids – black, white, Asian – were chatting in the park during the lunch hour. Doubtless it has the pervasive problems brought about by austerity and Brexit, but a mixed race boy in 2020 would not stand out painfully, as Karim does in the novel.

Growing up in Bromley today would certainly be very different from forty years ago when the novel was set. Crucially, the area is now casually multicultural and groups of school kids – black, white, Asian – were chatting in the park during the lunch hour. Doubtless it has the pervasive problems brought about by austerity and Brexit, but a mixed race boy in 2020 would not stand out painfully, as Karim does in the novel.

Black Lives Matter has demonstrated that racist violence is not a thing of the past, but at least no one has to suffer in silence. Through its wit and honesty, its sweetness and brutality, The Buddha of Suburbia made speaking about the essential questions of class, sex and racism that much more possible.

Susie Thomas, 2020

Further Reading

Hanif Kureishi’s archive is lodged at the British Library. The online collection contains interviews and articles on his work, including Zadie Smith’s brilliant account of passing round The Buddha of Suburbia under the desk at school.

https://www.bl.uk/20th-century-literature/articles/zadie-smith-on-the-buddha-of-suburbia

Hanif Kureishi, My Ear at His Heart: Reading My Father, Faber and Faber, 2004

Hanif Kureishi, ‘Knock, Knock, it’s Enoch’, Guardian (12 December 2014):

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/dec/12/enoch-powell-hanif-kureishi

Hanif Kureishi, ‘There were no books about people like me’, Guardian (25 April 2020):

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/apr/25/there-were-no-books-about-people-like-me-so-i-wrote-one-myself-hanif-kureishi-on-the-buddha-of-suburbia

Bradley Buchanan, Hanif Kureishi, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007

Susan Alice Fischer (ed.), Hanif Kureishi: Contemporary Critical Perspectives, Bloomsbury, 2015

Bart Moore-Gilbert, Hanif Kureishi, Manchester University Press, 2001

Ruvani Ranasinha, Hanif Kureishi, Northcote House, 2002

Sukhdev Sandhu, ‘Pop Goes the Centre’ in London Calling: How Black and Asian Writers Imagined a City, Harper Collins, 2003

Nahem Yousaf, Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia, Continuum, 2002

All rights to the text remain with the author.

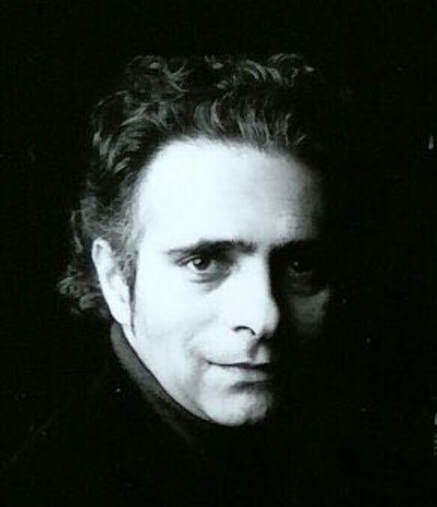

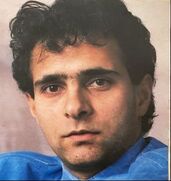

Many thanks to Hanif Kureishi for permission to use photos of him when young – these remain his copyright.