Ken Worpole

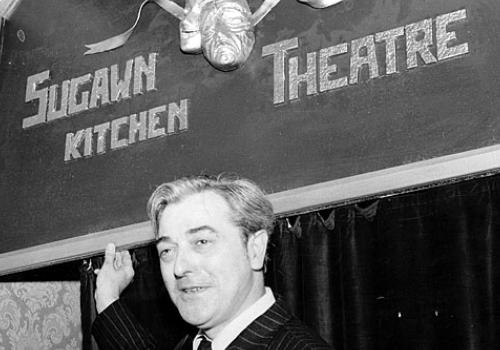

Jerry O’Neill was the quiet, but charismatic manager of The Duke of Wellington pub in Balls Pond Road, Hackney, from 1967 to 1980. This was a pub which sold Irish newspapers and cigarettes and had a billiard hall at the back which O’Neill – a man of serious literary interests – converted into The Sugawn Theatre. The pub and the theatre became a meeting place for Irish writers and theatre people, as well as a venue for all kinds of performances. I got to know him a little as a result of organising poetry readings there in the 1970s. Born in Limerick in 1921, O’Neill worked for Barclays Bank in Africa for many years before arriving in London towards the end of the 1960s to run the pub.

As well as being something of an impresario for Irish culture in London, O’Neill himself began to write towards the end of his days as a publican, firstly with the play ‘God is Dead and Living on Balls Pond Road’, and then with a sequence of six very fine novels, the first two of which, Open Cut (1986) and Duffy is Dead (1987), deal specifically with the hard and dangerous lives of Irish building workers in London, lives often lived physically in extremis.

Of all the novels, and they are all terrific, Duffy is Dead is my favourite, as it achieves an almost Beckett-like mixture of humour and tragedy, set largely within the classical unities of time and place: a pub in Hackney mostly over twenty-four hours, during which two Irish labourers, Mackessy & Neelan, attempt to raise enough money to bury their drinking companion, Duffy, who has suddenly died of heart failure on a pavement in Holloway Road. For this they involve the landlord of the pub himself, Calnan, a world-weary Irishman, who himself has problems with drink. He also has to deal with the local police who constantly harrass him for some of his clientele’s republican sympathies, and the wayward, unhappy lives of many of other customers, for whom the pub is the only home they know.

To every pub its guv’nor and to the guv’nor his sheet-anchor. At half-past ten, with a rattle of keys, Morgan came: brisk, stocky, white teeth always ready to smile, or grin, in warning. Brennan stood by the door for him and announced like a bellman in plague, ‘Duffy is dead.’

‘Lucky,’ Morgan said; he was moving, peeling off his coat, expressionless.

Calnan watched the traffic: its creep and twist was an endless stool with some moist sickly fascination that held him there. Reflected in the window, too, he could see the bar behind him. Morgan, assessing, rearranging, planning his day, looking now at the ravaged brandy bottle, lobbing it the length of the counter to his waste-bin. Calnan drew in breath and the long exhalation clouded the window. He rubbed it carefully with his handkerchief: he could see Brennan now, rolling a cigarette, the mop standing in dirty water.

‘We shouldn’t joke about it,’ Brennan said with an air of foreboding. ‘Duffy. God rest hik this day in the Divine Presence.’

‘Your mop’s drying out,’ Morgan told him.

‘Dropped dead!’ Brennan said with all the fearful undertones of meeting God with an unwashed soul. ‘Outside the Bank at the Archway.’

‘Breaking in or running out?’

For over two hundred years much of the most dirty and dangerous work in the building trade in London was done by Irish immigrants, yet their lives have only very occasionally been given serious fictional representation: Tim O’Grady’s I could read the sky (1997), with photographs by Steve Pyke, is exemplary. Edna O’Brien has published a series of short stories about such men, in Saints and Sinners (2010), also very fine and deeply sympathetic. There are others. However, Duffy is Dead, is perfection itself. It has wonderful comic set-pieces in the bar, at the undertaker’s, all on a fast-flowing tide of Guinness and brandy. It has pathos and a deep understanding of the lives of men without women, who have no papers of identity, who change their names with every job, who live outside the state in a no-man’s-land of casual work, poor health and precipitate death, and yet bounce back from the blows through the comradeship of a shared mordant humour.

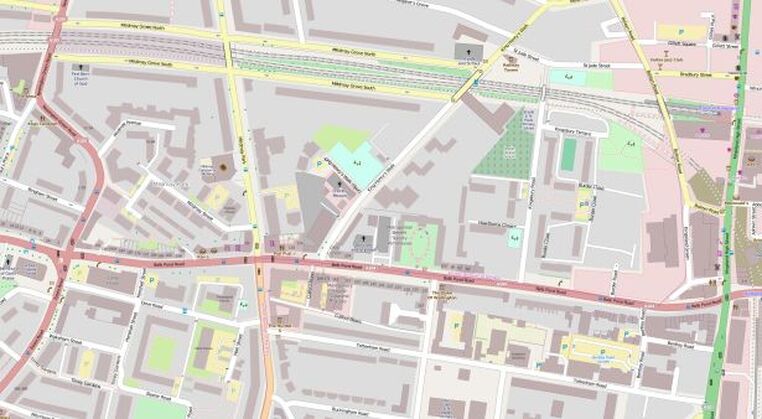

He walked the long stretch from Dalston to Shoreditch Church and stood looking at the roads fanning out to Hackney, Bethnal Green, Gardiner’s Corner, the City, London Bridge, Clerkenwell. This was his London, always traces of elegance but like himself growing old. Shoreditch Church, at the gates of the City, was always reassuring in the stillness of early morning.

The novel also captures wonderfully the borderlands of Dalston and Highbury Corner in the 1970s, where, in between streets exhibiting growing gentrification, an older, poorer life of tenement living, street markets, and corner pubs, still survived. O’Neill surely deserves a revival of critical interest, and a starting point for anybody interested in Irish London is the fully realised dark comedy of Duffy is Dead.

Ken Worpole is a former English teacher and oral historian who has lived in Hackney for more than forty years. His 1983 book Dockers & Detectives (revised edition 2008) brought to light many forgotten writers of the 1930s and ’40s, and he has written biographical introductions to Alexander Baron’s King Dido (Five Leaves, 2009) and Simon Blumenfeld’s Jew Boy (London Books, 2011). He has also written books about public architecture, landscape and social history and is Emeritus Professor at The Cities Institute at London Metropolitan University. His website is www.worpole.net

All rights to the text remain with the author.