Tony Murray

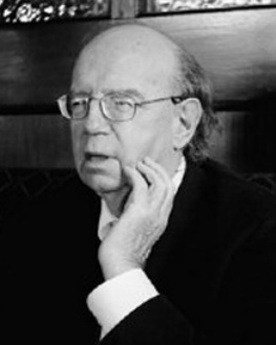

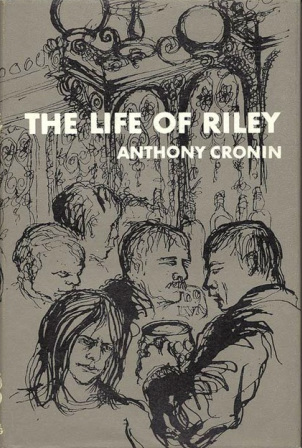

Anthony Cronin is best known these days as a respected elder statesman of Irish arts and letters. But, in the immediate post-war years he was, along with playwright Brendan Behan, novelist and columnist Flann O’Brien and poet Patrick Kavanagh, a fully paid-up member of the Irish literary rat pack. His novel, The Life of Riley (1964) is a fascinating insight into the preoccupations and habits of his peers in Dublin and London during this time. Whilst only the latter part of the novel is set in London, it is here where some of the sharpest and most entertaining critiques of literary pretensions appear. One of only two novels published by the writer, who is better known for his poetry and literary biography, it was an almost forgotten comic gem until republished by New Island Books two years ago.

The prospect of pursuing a literary career in the conservative moral climate of mid 20th century Ireland was seriously circumscribed. Literature was a key target of the draconian censorship laws passed after independence by the ironically named Irish Free State. As a result, many aspiring writers were forced to seek (in the time-honoured fashion) fulfilment of their ambitions abroad. For centuries, London had provided Irish writers and artists with an international market for their work. As a global hub of theatre and publishing, and by 1945 more physically accessible than before, it once again became a favoured destination for many Irish writers of the time.

The prospect of pursuing a literary career in the conservative moral climate of mid 20th century Ireland was seriously circumscribed. Literature was a key target of the draconian censorship laws passed after independence by the ironically named Irish Free State. As a result, many aspiring writers were forced to seek (in the time-honoured fashion) fulfilment of their ambitions abroad. For centuries, London had provided Irish writers and artists with an international market for their work. As a global hub of theatre and publishing, and by 1945 more physically accessible than before, it once again became a favoured destination for many Irish writers of the time.

Cronin’s often wickedly funny novel suggests that some writers of this particular generation, having struggled to locate the bohemian lifestyle they aspired to in Dublin, created a sometimes fantastical Irish version of such a world in the bars of London’s West End in the 1950s. Brendan Behan and Patrick Kavanagh both spent considerable periods of time in London exploiting (in their differing ways) the long-established persona of the stage Irishman to further their careers. Cronin was well placed as a close friend of both men to observe such shenanigans at close range and the somewhat naïve but sardonic anti-hero of The Life of Riley provides the vantage point for a string of wry and witty observations on the literary pretensions of the author and his peer-group.

In the preface to the novel, Cronin assumes the role of his protagonist’s literary executor by informing his readers that the ensuing narrative consists of the remnants of an autobiography by one Patrick Riley which was discovered amongst the writer’s ‘socks, rags and papers after his death’. Riley’s account of his journey across the Irish Sea begins after he is assured, by the socialist editor of a literary magazine in Dublin, that it is only by living the life of a ‘down and out’ amongst the dereliction of post-war Britain that he will produce anything of contemporary social and political significance. However, when he arrives at a Camden Town hostel for homeless men, it is not so much the English but the Irish underclass that Riley discovers:

The Irish were there in force and the dialoctic [sic] was in full swing; indeed it was all that the small group of harassed English officials who ran the place could do to prevent it getting out of hand altogether; it took all the immense pseudo-moral authority of the English lower middle classes to prevent large-scale massacre on Saturday nights.

Cronin paints a somewhat ghettoized and stereotyped picture of the Irish in London here, but Riley and his compatriots can be seen as part of a wider experience of itinerancy in the city. This is particularly evident with regard to his temporary residence at the Rowton House hostel or ‘spike’ (as they were commonly known).

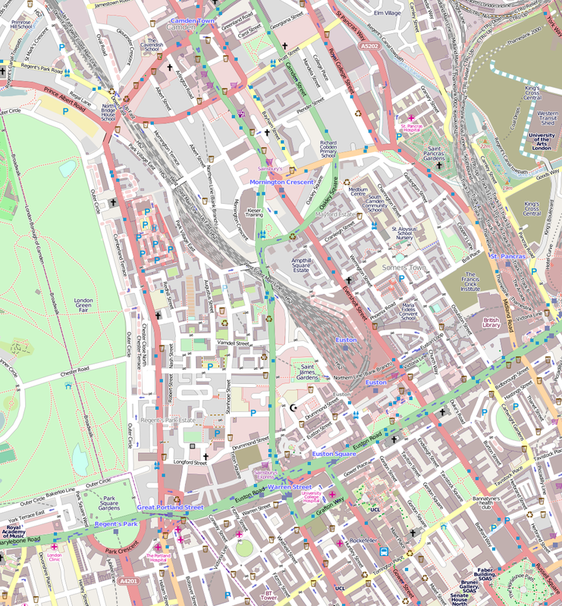

A connection between such establishments and the Irish can be found within a long-established tradition of British itinerant autobiography. Two of the best-known examples of this genre provide brief but illuminating glimpses into interactions between Irish and other itinerants in London. In Autobiography of a Super-tramp (1908), William Henry Davies describes how he made friends with Flanagan (an Irishman from County Mayo) in a Rowton House in Southwark. Twenty-five years later, in Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), George Orwell describes how an Irish tramp helped him find a bed for the night at a sister establishment in the East End. The hostel in Camden Town where Riley stays later changed its name to Arlington House and those interested in seeing one of the last establishments of its kind left standing in Britain can find the recently renovated building on Arlington Road near Camden Town tube station.

During periods of political tension between Ireland and Britain (as was the case in the 1950s following Ireland’s neutrality during the war) latent anti-Irish racism often bubbled to the surface. It is something Riley experiences first-hand from an official at the National Assistance Board, who describes his incomprehension of the British social security system as ‘a bit too Irish’. As a popular site of settlement for Irish migrants in London dating back to the mid 19th century, Camden Town (like Kilburn) has a mythical status in the Irish diaspora. But, as well as discovering the Irish, it is here that Riley has encounters with other equally marginalized ethnic groups in the city. He observes, for instance, how each of them has its own habits and clearly defined domains to which it gravitates within the locality: ‘the Irish to the Rowton and the adjacent pubs, there to continue their temporarily interrupted quarrels; the Cypriots to the room over the caff; the Maltese to check the girls’ earnings’.

By sending Riley to the Rowton House, Cronin consigns his protagonist to the vagaries of a discrete London Irish subculture in Camden Town, but by sending him to the Stork (a fictional version of a pub near BBC Broadcasting House), he places him within a wholly different yet no less rarefied migrant milieu in Fitzrovia. Described in the author’s memoir Dead as Doornails (1976) as ‘much frequented by Hibernophiles who worked for the corporation in various capacities’, the Stork is Cronin’s opportunity to ruthlessly satirize an incestuous clique of Anglo-Irish literati who drank there in the 1950s.

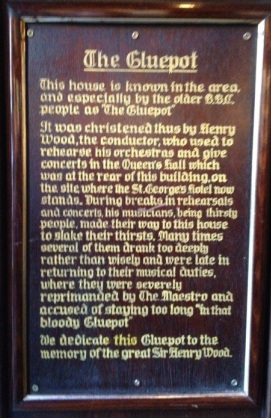

The precise inspiration for the pub was The George, which is located at the junction of Great Portland Street and Mortimer Street. It has more recently been used as the location for another comic novel about an Irish radio producer in Maurice Leitch’s Tell Me About It (2007). In Cronin’s day the pub was popularly known as ‘The Gluepot’ as a plaque inside the door explains. The sobriquet is a reference to the fact that once inside, its regulars (many of whom were writers and musicians with the BBC) found it almost impossible to leave.

The characters with which Cronin populates the bar include Wally Coosins (based on H. A. L. Craig), a man given to flamboyant Hiberno-Irish idioms; Billy Boddells (based on W. R. Rodgers), who speaks in ‘gnomic pseudo- proverbs, indecipherable to the rational mind’; and Casper McLoosh (based on Louis MacNeice), described as a ‘dour, craggy and hard-headed’ poet who, according to Coosins, ‘has the words to tear the bejasus out of reality’.

The characters with which Cronin populates the bar include Wally Coosins (based on H. A. L. Craig), a man given to flamboyant Hiberno-Irish idioms; Billy Boddells (based on W. R. Rodgers), who speaks in ‘gnomic pseudo- proverbs, indecipherable to the rational mind’; and Casper McLoosh (based on Louis MacNeice), described as a ‘dour, craggy and hard-headed’ poet who, according to Coosins, ‘has the words to tear the bejasus out of reality’.

Coosins, who takes Riley under his wing, pays him ten shillings a day to buy drinks for members of the Anglo-Irish cabal, in the belief that by ingratiating himself with them, the aspiring young writer will secure work with the BBC. But Riley is somewhat reticent. Bemused by the Hibernophiles’ intoxicated performance of Irishness, he considers both their ethnic and class credentials somewhat suspect.

Far from hampering their style or bringing a blush of shame to their cheeks, their membership of the traditionally oppressing class seemed to drive them on to a veritable frenzy, a sort of dervish dance of Irishry, which was to me a wonder to behold. The celticism of their speech sometimes resulted in a strange incoherence, not to say raving. The effect was of delirium.

The Stork, like the Rowton House, therefore, is an arena for stage Irishness, its actors indulging in a collective form of Paddywhackery where linguistic pyrotechnics render myth and reality virtually indistinguishable.

It is not long before Riley himself also begins to live out the fantasy of the ‘exiled Irish writer in London’. But it is a role with which he does not feel entirely comfortable, aware of the dangers of a personal identity being swamped by a public persona. ‘We become,’ he recalls, ‘what we pretend to be, and I found myself, to my extreme confusion, metamorphosing under my own eyes’. Despite these forebodings, however, he is unable to resist the offer of an invitation to dinner with Amelia, ‘a lady in Hampstead’ with contacts at the BBC.

During the course of the evening, Riley agrees to dig a trench for her in the garden, which she promises to repay by providing him with food and lodging and a desk to write at. After finishing the job, he is charged to come up with scenarios for radio programmes, including a documentary about life in the Rowton House. However, fearing he is in danger of becoming ‘Amelia’s synopsizing and pick-axe wielding slave’, Riley eventually decides to extricate himself from an underpaid and demeaning business relationship.

Consigned in the closing pages of the novel to wander the streets, he must now follow in the footsteps of his countrymen, such as the eponymous hero of Samuel Beckett’s Murphy (1938) and Micil Ó Maoláin, the protagonist of Padriac Ó Conaire’s Deoraíocht (1910). Having burned any remaining evidence of his script-writing ambitions, Riley signs off, in suitably existential style, with the following lines: ‘It was high April, verging on May, and warm in the side-roads of Hampstead, I had absolutely no place to go’. Voluntary exile, therefore, is where Riley may finally have found, like his itinerant London Irish forebears, the anonymity he had always secretly craved.

Tony Murray is Director of the Irish Studies Centre at London Metropolitan University. His research is in literary and cultural representations of the Irish diaspora and he has run the annual Irish Writers in London Summer School since its inception in 1996. His book, London Irish Fictions: Narrative, Diaspora and Identity was published by Liverpool University Press in 2012. For more details about this title, visit the Liverpool University Press website.

Further Reading and Acknowledgements

Samuel Beckett, Murphy (London: Routledge, 1938)

Anthony Cronin, Dead as Doornails (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1976)

Donall Mac Amhlaigh, Schnitzer O’Shea (Dingle: Brandon, 1985)

Padriac Ó Conaire, Deoraíocht (Baile Átha Cliath: Conradh na Gaeilge, 1910) available in English translation as Exile (Inverin: Clo Iar-Chonnacht, 1994)

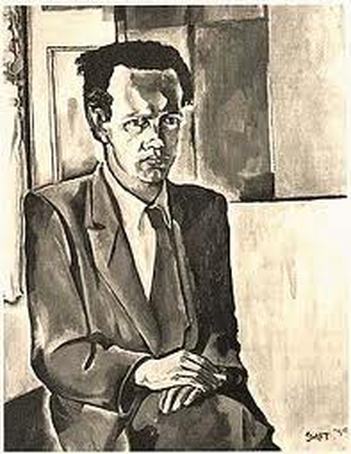

Anthony Cronin portrait by Patrick Swift from Wikipedia

The photographic portrait of Anthony Cronin at the top of the page is posted here with the kind permission of Niall Hartnett – more of his work on Irish writers can be seen here

Image of Arlington House from the ‘Ravish London’ website

All rights to the text remain with the author.