Rachel Lichtenstein

This is the introduction to a new edition of Robert Poole’s London E1.

It is posted here with the kind permission of Rachel Lichtenstein and of the publishers, Five Leaves.

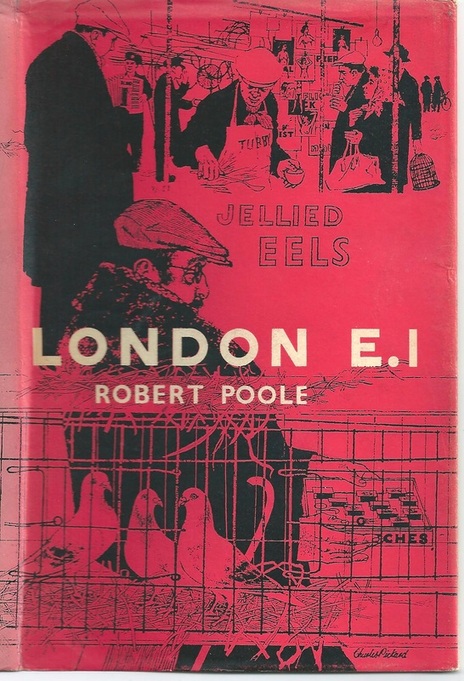

On the back cover of the first edition of Robert Poole’s long-forgotten first, and only, published novel, London E1 (Secker & Warburg, 1961) is a black and white head and shoulders shot of a slim white man, with a high forehead, a slightly receding hairline, a long square jaw and prominent ears, who looks remarkably like the English comic actor Stan Laurel. He is looking directly into the camera and appears to be suppressing a smile. Underneath the photograph are instructions for the reader to look inside the book jacket for some details of Robert Poole’s ‘highly unusual career.’

Here we learn the author was born in Stepney in 1923, ‘about fifty yards from Brick Lane.’ After leaving school without any qualifications, he worked as an office boy, a telegram boy and then in a war factory making gun brushes, before volunteering for the Navy where he became a wireless operator on anti-U boat detection and was later involved in the Pyu landings in Burma. After being demobbed he spent some time as a garage store assistant and an estate agent. At some point he fractured his spine in a car crash and, whilst recovering in hospital, he began writing short stories. Then he joined the Merchant Navy as a steward, jumped ship in New Zealand, changed his name ‘to dodge police’ and became a successful broadcaster and scriptwriter for N.Z. radio, as well as a radio actor, whilst also working as an import agent and a sub-editor on a daily paper. The police finally caught up with him in New Zealand and after spending four weeks in the ‘clink’ he was deported back to London.

He sold clothes in Oxford Street for a while. In 1958, at the age of 35, he moved to Margate and ran the bingo stall in Dreamland, which he described as being ‘fabulous!’ Eventually he showed his short stories to his friend, the bestselling Australian author Russell Braddon, who ‘liked them.’ Encouraged, Poole developed these stories into London E1.

He sold clothes in Oxford Street for a while. In 1958, at the age of 35, he moved to Margate and ran the bingo stall in Dreamland, which he described as being ‘fabulous!’ Eventually he showed his short stories to his friend, the bestselling Australian author Russell Braddon, who ‘liked them.’ Encouraged, Poole developed these stories into London E1.

A search for further information on Robert Poole drew a blank. He seemed to have vanished without trace after publication. However, after trawling through various genealogical websites, I found some brief entries on his family history.

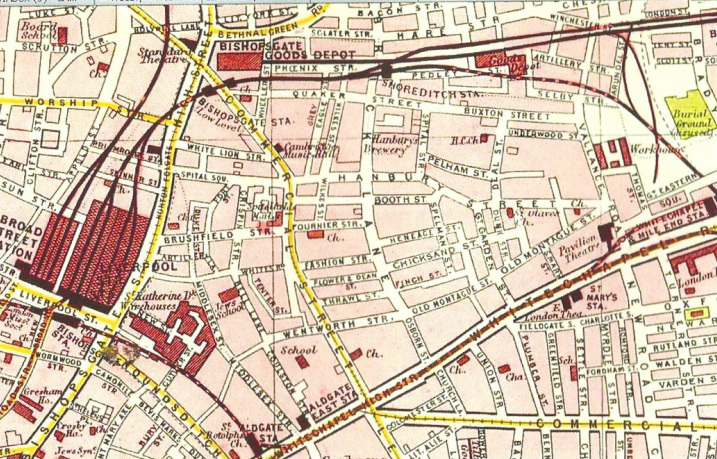

A relative of Poole’s had traced the family tree back to the 1830s, discovering generation after generation living in Whitechapel, Stepney or Bethnal Green. His parents, Elizabeth Peddler (a domestic servant) and George Poole (a barrow boy and peddler) had eleven children in total. Robert was the ninth, two died in infancy.

Further notes on George Poole revealed he had a fruit and vegetable stall under the Brick Lane arches, exactly like the character of Mr Wilson, the father in the novel. He was also a heavy drinker and ‘not a good husband. He visited local pubs while the children went hungry. … He used to treat himself to fish and chips and give the children the left over fish skins. I also learnt on this website that Robert Poole had died at the age of just forty, from an accidental overdose of painkillers, only two years after his novel had been published.

How the novel was received on publication has been hard to gauge. After searching through the British Library’s online newspaper catalogue for reviews of the book in 1961, I came across a single one-line reference to an article by the literary giant Anthony Burgess no less (best known for A Clockwork Orange). From 1961–63 Burgess worked as a fiction reviewer for The Yorkshire Post, mainly covering niche novels, most of which, much like London E1, are now long out of print. In a review dated 23rd February 1961, entitled ‘Round the World in Five Novels’, Burgess wrote about William Styron’s Set This House on Fire, Jim Kirkwood’s There Must Be a Pony, William Ash’s The Lotus in the Sky, Katharine Sim’s The Jungle Ends and Robert Poole’s London E1. The section of this article covering London E1 is brief and disparaging in parts: ‘the tale goes over ground already well trodden — “Probation Officer” stuff: what leads lads astray? (“…generation…We didn’t believe anything real enough.”)’ However, Burgess enjoyed the scenes where Poole described ‘authentic aromatic Stepney’ in the first person and felt the novel to be ‘promising enough for me to feel interested in seeing what Mr Robert Poole (he has vitality and flow) can produce next.’

I first read London E1 about seven years ago, whilst writing my own book on the stories, memories and history of Brick Lane. The oral historian and long-time resident of Stepney, Alan Dein, had found a battered original copy at a jumble sale and thought it might interest me. It did. Immensely. I was astonished to discover the lost world within.

The novel is set in and around Brick Lane, both during and directly after the Blitz, and intimately describes the daily lives of a community who are so often overlooked in East London literature — white working-class cockneys.It also documents a period of flux in the history of the place — the war years — when the Jewish and white working class communities were still very present in the area and the first Asian migrants were beginning to settle there. The relationships and tensions between these different groups are, for the most part, well told, with an attention to detail that suggests true-to-life fiction.

The book prologues with the protagonist of the novel, Jimmy Wilson, imprisoned for murder, staring longingly through the tiny barred window of his cell at the distant silhouette of the two tall slender chimneys of Truman’s Brewery on Brick Lane — the setting for most of the novel. We next see Jimmy brawling on the streets with ‘The Luxton Street Gang’ and a group of local Jewish kids. ‘You wait ’til I get you indoors — I’ll tan the living daylights out of you,’ screams Mrs Wilson, Jimmy’s mother, as she pulls the boys apart. I expect Luxton Street refers to Buxton Street, a narrow turning just off Brick Lane. For my book on the area I interviewed an elderly Jewish lady called Sally Flood, who had grown up there in the 1930s. She described the street as ‘a mixed place of Jews and gentiles.’ She went to Buxton Street Junior School, where the majority of children were Jewish, ‘but we didn’t mix, the Jewish and the non- Jewish children.’

London E1 accurately describes the way these two cultures lived side by side, sometimes coming into violent conflict, other times interacting amicably. The Luxton Street boys briefly befriend Wolfie (the leader of the Jewish gang) and become fascinated by his forthcoming Barmitzvah ceremony — a mysterious and dangerous sounding rite of passage in their eyes. Jimmy’s mother takes in washing for a Jewish neighbour. His older sister Janey works as a dressmaker for Jewesses. Jimmy earns extra cash as a Shabbas Goy, lighting fires and candles on the Sabbath for Orthodox families whose observance forbids it. His elder brother Billy, joins the Blackshirts before the war and Jimmy’s classmates are clearly antisemitic, chanting ‘England for the English, down with the Jews’ in the playground.

The novel also describes, sometimes in exotic terms, the emerging Asian community. The women with their ‘swirls of colour’ and the lascars, the seamen who had jumped ship at Limehouse and ‘slept on bare mattresses on the floor, ten or twelve to a room.’ Jimmy watched the first Indian café opening in Brick Lane, ‘then suddenly they seemed to be everywhere… their spiced pungency mingling with the sweet syrupy odour from the brewery. With the arrival of the curry houses he noticed painted emblems appearing on hoardings around Whitechapel and Brick Lane, circles with lightning flashes and the words ‘Vote Fascist’ on them, which were soon painted over with slogans saying ‘Vote Communism’.

The Wilsons live in a two-room run-down tenement block off Brick Lane. There are nine children in total (just like in the Poole family) but only Jimmy and his older sister Janey remain at home. The family live on the bread-line, the only real piece of furniture in the flat is the parents’ bed but there is no mattress, old coats are stretched over the springs in an attempt to provide some comfort. Each week Jimmy’s mother tries to stop ‘the old man’ spending the rent money down the pub, with the few pence she manages to save she buys their groceries: a sheep head if they are lucky and some bruised vegetables from the market.

There are many vivid and lively scenes in the first part of the book: Jimmy lifting apples from Spitalfields Market, playing Tarzan on the shafts of the empty drays around the brewery or interacting with some of the local characters, like Prussian Pete, a veteran of the Great War, who sells bootlaces and matchboxes, and Mad Mary, the meths drinker, who sings Irish ballads with her cronies near Christchurch.

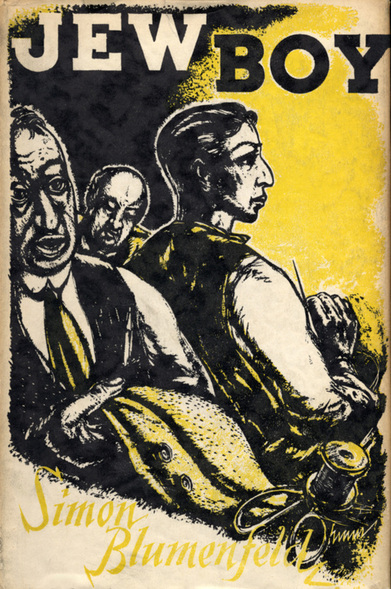

London E1 is comparable in many ways to Simon Blumenfeld’s first novel Jew Boy (1935). The central characters are both bright, young, frustrated (sexually and otherwise) males, living in poverty in East London, desperate to escape. From the beginning of both of these stories it is clear this will never happen.

London E1 is comparable in many ways to Simon Blumenfeld’s first novel Jew Boy (1935). The central characters are both bright, young, frustrated (sexually and otherwise) males, living in poverty in East London, desperate to escape. From the beginning of both of these stories it is clear this will never happen.

When Jimmy manages to win a scholarship to attend the high school he is immediately beaten up at school for being a ‘sissy’. On returning home his father gives him a black eye and he is told to never mention it again. The only person who encourages him to better himself is Peggy, a well-spoken white woman who ‘services’ Indian seamen to pay for her mixed race child Jalani (commonly known as Pinkie) to attend private school, far away from Brick Lane. Her luxurious flat, with its carpet, lampshades and divan, is so overwhelming for Jimmy the first time he visits that he is rendered speechless. Peggy tells Jimmy to work hard at school and improve his grammar or he’ll be stuck in the East End with a ‘dead end job in the brewery or a factory, you’ll go nowhere, do nothing, see nothing.’ With her assistance he begins his self-improvement. At school, he gets into trouble for using big words but, undeterred, he continues to visit Peggy, who gives him informal elocution lessons when she is free from paying customers.

In one of the most dramatic scenes in the book, Jimmy and his school friend Davey hitch a ride on the back of a brewery dray. Davey falls off and is run over by the cart behind and killed. In great distress, Jimmy goes to Peggy for comfort, where he meets Pinkie for the first time. He is instantly infatuated with the beautiful, brown-skinned, sophisticated twelve-year-old, who ‘knows about classical music and has her own gramophone.’ Book Two opens to the backdrop of war; the East End has become a different place, with constant air raids, blackouts and bombsites. The market is no longer filled with ‘swirling crowds and shouting vendors…. there was a feeling of tension… people still looking for food or clothing-bargains did so quickly and quietly, fluttering across the streets like distressed and nervous birds.’ Jimmy has left school by this time but he is still living at home, working the stall with his father. His mother ‘wishes ’e’d been able to go to the ’Igh School when ’e won the scholarship, but what was the good? They only got their ’eads full o’ strange ideas.’

In the most memorable wartime pub scene in the book, the Wilsons visit their local, the Two Bakers, during an air raid. The pub is packed: ‘the thick granite walls were believed to give more protection than the shelters.’ A small group of ‘Indians’ nervously sipped brown ales in one corner. A group of Jewish women sit in another with Mrs Behan, wearing the ‘fruit salad hat she had bought to celebrate the victory of 1918.’ As the pub becomes busier and busier and the smoke haze grows thicker and thicker, Mr Wilson starts playing the piano, ‘feet shuffled and a gradual stampeding was taken up by the whole crowd.’ During the frenetic ‘knees-up’ the pub receives a direct hit — the room fills with acrid dust and smoke, women scream, glass shatters, debris falls and Mrs Behan is found slumped in a corner, with her fruit-salad hat sliding slowly to one side, temporarily hiding ‘the bright red stream that pulsed and jetted beyond her shoulder.’ Jimmy runs through the deserted, glass-glittered streets to find Peggy buried under a pile of wreckage, badly injured but alive.

Soon after, Jimmy begins scavenging the local bombsites for scrap metals to sell on the black market. He wants the cash to buy a new suit. His parents laugh out loud when he tells them. ‘Why would received ’ya need a suit to work in the broory,’ his father screams. After recognising how profitable the activity is Jimmy persuades his old school friend, Tommy Copper, to help him collect ‘Blooey’ from bombsites near St Paul’s and sell directly to the dealers, cutting out Blind Billy, local gangster and head of the scrap-iron gang. As they enter the ‘dead part of the great city’ miles and miles of rubble make streets unrecognisable. Every night Jimmy and Tommy enter the dark basements of these precarious ruins to recover scrap, which is dangerous and highly illegal work. When Pinkie returns to the East End to look after her mother (who is still gravely ill in hospital), the reader is fully aware she will be the downfall of Jimmy. This section of the novel is less successful than others. Pinkie uses Jimmy mercilessly, aware of his deep feelings for her. His hard-earned savings quickly evaporate. Peggy’s money also dries up and, to make ends meet, Pinkie starts working for Blind Billy.

When Jimmy’s handsome older brother, Boy-Boy, arrives home after years of no contact, with a young son and a heavily pregnant girlfriend (a plain Northern girl called Maisie) the Wilsons plan a ‘proper wedding party’. Crates of beer, bottles of spirits and ‘two ferkins of ale’ are delivered from the pub. Tables are erected in the court and covered with plates of curling corned beef and boiled bacon sandwiches. Jimmy proudly wears his brand new pin-striped suit and invites Pinkie to the party. In the afternoon, after a long session in the Two Bakers, the wedding party returns to the court, but when Pinkie arrives the merriment abruptly stops. ‘There was only the shrill blare of the gramophone as everyone stared.’ Mrs Wilson, who doesn’t like ‘blackies’ or ‘Indians’ begrudgingly allows her to stay. Soon after, Blind Billy turns up with a bottle of ‘Shampain’ and tries to recruit Jimmy as his field-officer in the East End, but Jimmy refuses. When Pinkie leaves the party in disgust, calling Jimmy’s family ‘animals’, he drunkenly goes home with his sister’s friend Rosie and loses his virginity. Depressed and exhausted, he seems to finally let go of all of his dreams: ‘it was no good to want things you weren’t born with. If you were born in Stepney you lived and died in Stepney.’

Two years later, the war is over and Jimmy is still living with his parents. He works for a brief time in an office but after fighting with a co-worker he is sacked. Slowly and manipulatively, Pinkie lures him into Blind Billy’s dark underworld of Soho clubs, drug deals, black market spirits and prostitution. After being beaten close to death outside one of these clubs Jimmy buys some knuckledusters from Bethnal Green Market, ‘he’d be ready next time. …’

He temporarily manages to escape the East End by joining the Navy but after a few years at sea he returns.Desperate to get back in touch with Pinkie, he eventually tracks her down in the red light district of Cable Street. He follows her home, knuckledusters in his pocket, where the story reaches its inevitable dreadful end.

Curious to know how much of the novel had been based on Poole’s own experiences, I followed some leads from the genealogical website and eventually managed to speak with his niece, Pam, who told me ‘Uncle Bob’ had grown up in Buxton Street, in a tenement block in a court. One of his childhood friends had been killed riding on the back of a dray. He had won a scholarship to the grammar school and his father did not let him go. As far as she knew he had not had an Asian girlfriend, but he did have one long-term girlfriend, called Midge. They were in a car accident together and she was killed: ‘He had a lot of girlfriends but he never got over Midge, he never married.’

When he returned from a stint in naval prison in Portsmouth (for jumping ship in New Zealand) he lived with Pam’s family in Stepney for about three years. ‘He had loads of jobs, but he couldn’t settle, he was always looking for something else. He lived life to the full at a great pace, but what he really wanted was to be a published author. He used to drive my mother mad. He would sleep a lot in the day and then type all night. All you could hear was this tap tap tapping. He was also a brilliant classical pianist, even though he couldn’t read music, he was self-taught. He had so much talent but was never fully recognised within his lifetime. He travelled a great deal but always wanted to come back to the East End, it was home, he loved the people, the atmosphere.’

She told me he used to drink heavily and had been on anti-depressants when he had died. The inquest recorded an open verdict but Pam believed it had been an accident: ‘He’d phoned me three weeks before and invited me to a party. He seemed happy.’ Before she rang off she told me Robert had been writing another book when he died, a novel called ‘Carnival for Shadows’. She did not know what it was about but said Secker & Warburg told the family they were going to hire a ghost writer to complete it. That was the last they heard about it.

Like Burgess, I would love to read this next work by Poole, but I doubt the manuscript even exists any more. For now, we are lucky to have this reprint of London E1. In my opinion it is not a literary masterpiece, but the scenes based on incidents from Poole’s own Stepney childhood are magical: the all-day wedding party in the court, children riding on the back of the brewery drays in Brick Lane, the destruction of ‘the local’ near Spitalfields Market during an air raid. These vivid and often humorous episodes really bring the novel to life and make this long-forgotten book a valuable and important document, both as a record of a bygone era and as a window into the closed world of a rapidly disappearing community.

Rachel Lichtenstein’s books on the East End include On Brick Lane (Hamish Hamilton, 2007), Keeping Pace: The Lives of Older Women of the East End (The Women’s Library, 2004), Rodinsky’s Whitechapel (Artangel,1999) and, with Iain Sinclair, Rodinsky’s Room (Granta, 1999).

All rights to the text remain with the author.