Colin Stanley

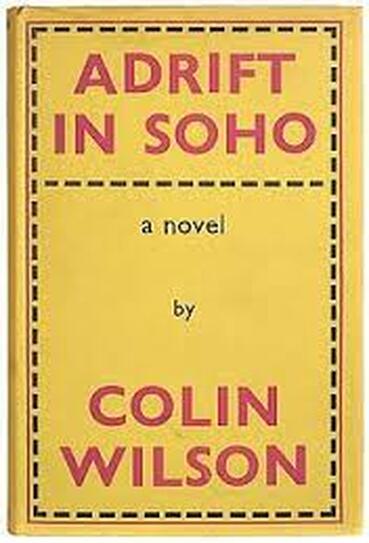

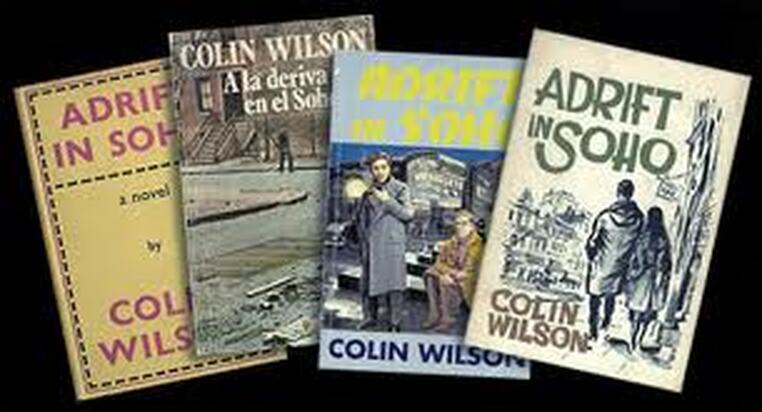

Adrift in Soho was Colin Wilson’s second published novel. It appeared on September 4th, 1961 in the trademark yellow Victor Gollancz dust-jacket and was published six weeks later by Houghton Mifflin in the US.

Released one year after Ritual in the Dark, it is a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story, set in the 1950s, about a young man from the provinces searching for freedom in London. In his autobiography Dreaming to Some Purpose (2004) Wilson explained that the novel had, in fact, started out as a collaboration between himself and an old Soho friend called Charles Belchier, otherwise known as Charles Russell, a Bohemian actor who appeared uncredited as the bandleader on the Titanic in the film ‘A Night to Remember’ (1958):

Released one year after Ritual in the Dark, it is a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story, set in the 1950s, about a young man from the provinces searching for freedom in London. In his autobiography Dreaming to Some Purpose (2004) Wilson explained that the novel had, in fact, started out as a collaboration between himself and an old Soho friend called Charles Belchier, otherwise known as Charles Russell, a Bohemian actor who appeared uncredited as the bandleader on the Titanic in the film ‘A Night to Remember’ (1958):

We had not been close friends in my Soho days, for Charles, like so many actors, was uninterested in ideas, so we had little in common. But after The Outsider came out, he contacted me, and came to stay with us on several occasions. And he asked my help finding a publisher for an unfinished autobiographical book called The Other Side of Town. As soon as I read it I saw that it was unpublishable in its present form—it was too short, and had no development. But the fragment fascinated me….For about a week I tried to rewrite it as a novel, then suddenly realised that I could not write the book from behind Charles’s eyes, so to speak; I had to put myself into it. So it turned into a story about a provincial youth who, like myself, has worked as a navvy in an attempt to avoid office work, and who goes to London in search of a more interesting life.

In the event, Belchier was paid £100 for his manuscript and it was agreed that he should receive a small percentage of the royalties. When interviewed by the ‘Sunday Express’ on September 10th, 1961 he said:

‘I do not mind. Originally I sent my book to Colin for him to do a preface. I was then going to sell it. But he said he would like to re-write it and I agreed. Money would be useful but I am a Bohemian and want freedom more than anything else.’

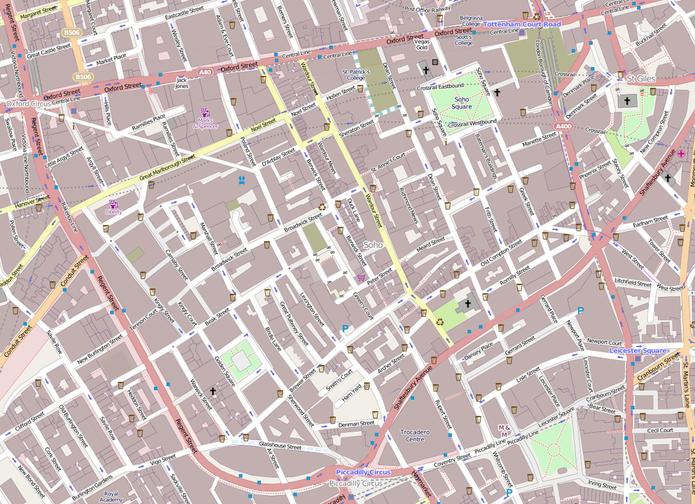

The character that Wilson introduced was Harry Preston and a short prologue describes his working life in the East Midlands (almost certainly based on Wilson’s home town of Leicester) after being dismissed from the RAF (as, indeed, Wilson himself had been) and before making the decision to seek his fortune in the Capital. After this prologue, the book is divided into two parts. In Part One, Harry arrives at St Pancras station and seeks accommodation at the Youth Hostel in Great Ormond Street. He then takes a tube ride from Russell Square to Leicester Square, walks up Charing Cross Road and has a cheap meal in a café on Tottenham Court Road. Retracing his steps, he has a drink in a pub on the corner of Old Compton Street, reflecting gloomily on the impersonal nature of the metropolis:

The whole city was a part of the great unconscious conspiracy of matter to make you feel non-existent…It is a monument to your unimportance, a perpetual gesture of disrespect from the universe to people who lack a sense of their own necessity. (22)

The next day he sets about finding lodgings. Using a copy of the ‘London Weekly Advertiser’, he finds an attic room in Courtfield Gardens, Earl’s Court, for two pounds fifteen shillings a week and decides, in order to save money, to spend much of his time in Kensington Public Library.

Back in the pub, however, he meets James Compton Street — an out-of-work actor — who takes him under his wing and escorts him into Soho for a meal (for which Harry, of course, pays). The rich character of James is based upon Charles Belchier himself who is, in fact, called Charles in the US editions. For fear that some acquaintance should claim to be identified in the novel, Gollancz’s legal advisers suggested that the name be completely changed to James Gerrard Street because Belchier often signed himself as ‘Compton Street’. A compromise was eventually arrived at.

Very much a charmer, James picks-up a young girl and persuades Harry to let them use his room for the night. Inevitably the landlady finds out and Harry is given his marching orders. His subsequent low opinion of landladies parallels Wilson’s own after his move to London in June 1951:

Why did such people exist? Why did she want to browbeat fellow human beings? It would be a very satisfying world in which her kind could be struck dead by the loathing they aroused… (30)

Back in Soho, James introduces him to a number of colourful characters including the ‘King of the Bohemians’ himself: Ironfoot Jack. Jack, otherwise known as ‘Professor’ J. R. Neave, was a real character who frequented Soho at that time. His right leg was shorter than his left and to overcome this he wore a surgical boot with an iron extension below the sole. His favourite haunt was the French coffee bar on Old Compton Street where he would often talk to friends and students from the nearby St Martin’s Art School on literature, art, philosophy, music and the occult. He carried a blue cloth bag around with him containing second-hand books, newspaper cuttings, notebooks and the typed manuscript of his life-story. Wilson’s description of him in Adrift… seems fairly accurate.

James proposes to Harry that they form a ‘league for mutual support’ in which they take it in terms to support each other for two weeks, using James’s know-how to live as cheaply as they can without working. He then proceeds to introduce Harry to the ‘Compton Street breakfast tour’ which involves sleeping on the midnight train from Waterloo to Staines, hitch-hiking back to London and freshening-up in the washrooms of the British Museum. Wilson, when famously sleeping rough on Hampstead Heath to save money, in the mid-1950s, made use of these very facilities himself before spending the rest of the day in the Reading Room working on Ritual In the Dark and, what was eventually his first published book: The Outsider.

This way of life soon palls, however, and Harry comes to regret his bargain, longing for solitude and a room of his own where he can read, write and think. It is this attitude that turns the novel into “a deliberate counterblast against all the ‘Beat Generation’ philosophy and ‘Angry Young Man’ stuff”, as Wilson wrote in a letter to his publisher. Those critics who described Adrift… as an English ‘beat’ novel, failed to appreciate that Wilson was not glorifying this way of life, as Belchier’s manuscript no doubt had…quite the reverse. Wilson himself had by then already ‘escaped’ from all that and from the round of London literary parties, functions etc, with which he had become embroiled, after the success of The Outsider in 1956, and moved away to Cornwall in order to pursue his life’s work in peace and quiet.

Harry meets a young girl from New Zealand, Doreen, and together they move into a room in a house in Notting Hill. This was based on Wilson’s own lodgings, during the mid-1950s, at 24 Chepstow Villas but again Gollancz’s legal advisers stepped-in suggesting he make the location a little more vague: it is described in the novel as the ‘Ladbroke Road house’. In ‘My Night with the Beatniks’, an article written for the ‘Sunday Dispatch’ on January 15th, 1961, Wilson describes a night spent at a Beat commune in London researching Adrift…. Unconvinced of the soundness of Beat philosophy, he wrote: ‘I give the whole craze another three years.’ The article itself caused some concern and was discussed in the House of Lords. A piece in ‘The Times’ on February 8th, 1961 reported that Lord Amulree thought the references to marijuana and preludin in the article might be deemed an incitement to commit an offence. Earl Bathurst, Lord in Waiting, replied that the article had been referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions who, fortunately for Wilson, felt there was insufficient grounds for prosecution. It was probably here that Wilson drew his inspiration for the scene at the end of Part One where Harry smokes marijuana and finds ‘the kind of muzzy happiness it created was the enemy of incisive thought or feeling’ (155). Despite the ‘swinging sixties’, Wilson maintained this stance, against the use of drugs to induce higher states of consciousness, preferring more intellectually-based methods.

It is at this stage that Adrift… moves on from Belchier’s memoir, away from Soho and into the much shorter Part Two of the novel. Wilson wrote in Dreaming to Some Purpose: ‘I soon used up all Charles’s plot, and decided to extend it with bits of my play The Metal Flower Blossom.’

This had been written by Wilson, in the early 1950s, for a group of teenagers, including the budding novelist Laura Del Rivo, who spent their evenings around Soho. When the group split up, and Wilson went off to Paris, the play remained unperformed and had to wait until December 11, 1960 for its premiere at the Palace Theatre, Westcliff-on-Sea—a one-off performance in front of an audience of 500. It did not appear in print as a play until 2008 when an anthology entitled ‘The Death of God’ and other plays was published by Paupers’ Press.

The central character is a Bohemian artist by the name of Ricky Prelati and it concerns him and the weird assortment of characters that drift in and out of his studio:

Because it was written for a group of friends, I wrote without the kind of inhibitions that might have bothered me if I was writing a “real play”. I tossed in a Hindu yogi, a devil worshipper… and a mad ballet choreographer… . I also threw in a naked model, a lady evangelist and a homosexual. (These were the days when homosexuality was illegal, and it was still regarded as vaguely scandalous).

It was this content, no doubt, that caused Lady Astor to ban its proposed production at Plymouth Arts Centre in 1957.

Like James, Ricky Prelati seeks freedom but whereas James drifts, Prelati creates. This need to create appeals to Harry and he goes off to the British Museum with the intention of making notes for a volume on the nature of freedom. The novel ends when Prelati’s work is discovered and, much to his disgust, he achieves fame overnight in the manner in which Wilson himself had achieved it in 1956, after the publication of The Outsider. Victor Gollancz was happy with the indeterminate ending, writing to Wilson that ‘it produces an effect like a Viennese perpetuum mobile…’ Sidney R. Campion, in his study of Wilson’s early work, The Sound Barrier (2011) concluded:

the indeterminate ending might be said to be prescribed by the subject. Even if [it] had continued for another fifty pages, there would have been no real ending….Harry Preston confront[s] a certain ‘existential problem’, a problem about the nature of freedom. [His] experiences in the course of the novel provide material for a solution…[it is] not the novelist’s job to offer the solution to the reader.

Despite the impression, given in this essay, of a somewhat disjointed hodge-podge, the novel works remarkably well. The evocation of Soho, during that fascinating period in the 1950s, and the descriptions of some of its characters, bring a vibrancy to the narrative. Anthony Rhodes in the ‘Times Literary Supplement’ (Sept. 8, 1961) wrote “From the moment the story opens the reader is lost, spellbound…” and predicted: ‘This is a small book—and in Mr. Wilson’s work it may well prove to be a minor one—but it is surely a signpost to a distinguished career as a novelist.’ Nicolas Tredell in his study The Novels of Colin Wilson (1982) wrote:

Adrift in Soho, for all its lightness, manages to be many things. A Bildungsroman; a picaresque tale; a documentary; a period piece; a fairy story; an investigation of freedom. After Ritual in the Dark, worked over many times, brooded-on obsessively by Wilson, it is a kind of release, a burst of light-heartedness. It also teaches a lesson relevant to Wilson’s future development as a novelist: that an apparently light-weight form could deal with serious themes.

Sidney R. Campion described Adrift… as ‘Wilson’s lightest work—from the point of view of size as well as content’ and it is true that this is not the usual novel of ideas we expect from Wilson the philosopher-novelist. But there are moments when insights break through such as when Harry is ‘overwhelmed by a kind of brainstorm of insight’ whilst walking down Tottenham Court Road, catching a glimpse of some illustrations of Egyptian statues through the window of a bookshop: ‘Something about their mathematical perfection excited me…made me tremble….’ (72). He recalls a similar ‘brainstorm’, when he was sixteen, which had encouraged him to ‘devote some time to clarify my vision of ‘life as it might be’, and the attempt brought me a new sense of purpose and concentration’ (71). This is the theme that permeates all of Wilson’s work whether writing about philosophy, psychology, criminology, music, literature or any of the many other subjects he set his mind to.

The novel was published in paperback by Pan Books in 1964 and was translated into French and Spanish but, after the mid-1960s, remained out-of-print in the UK for 25 years becoming a much sought-after Wilson title; second-hand first editions changing hands for very high prices. Then in 1993 it was reprinted by Brainiac Books, with a cover illustration by Barbara Bennett, depicting a duffle-coated Wilson, sitting under Eros at Piccadilly Circus. In 2011 it was reprinted again by Five Leaves as part of their ‘Beatniks, Bums and Bohemians’ series.

In Dreaming to Some Purpose Wilson recounts the rather tragic conclusion to Charles Belchier’s life:

In the summer of 1968, he wrote to me from some island in the Mediterranean, telling me that he had found the perfect way of life, beach-combing, dozing in the sun and smoking pot. Six months or so later, I received a press cutting from his girlfriend: it is from the ‘Daily Express’ of 6th December 1968:

“A 43-year-old Englishman arrested for peddling dangerous drugs in West

Germany committed suicide in his cell in Heilbronn today. He was named as

Charles Belchier of no fixed address”.He and two associates were arrested after they were found with hashish worth £1,500 on the black market. Apparently Charles had hanged himself. His girlfriend was convinced that he had been murdered by other smugglers to keep him from talking, and I have to agree that this is plausible—I feel Charles loved life too much to kill himself.

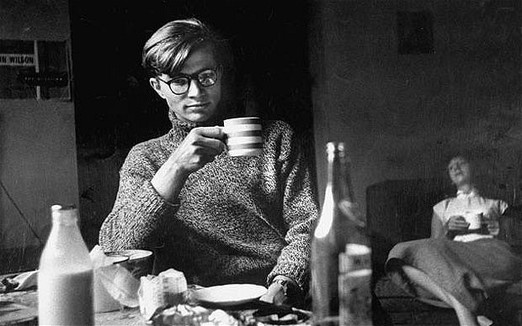

Wilson himself was born on June 26th, 1931 — the first child of Arthur and Annetta Wilson. At the age of eleven he attended Gateway Secondary Technical School, where his interest in science began to blossom. When just fourteen he compiled a multi-volume work of essays covering all aspects of science entitled A Manual of General Science. By the time he left school at sixteen, however, his interests were already switching to literature. His discovery of George Bernard Shaw, particularly Man and Superman, was an important landmark. He started to write stories, plays, and essays in earnest—a long ‘sequel’ to Man and Superman made him consider himself to be ‘Shaw’s natural successor.’

After spending some time wandering around Europe, he arrived in London on June 7th, 1951, aged just 19, staying at the youth hostel in Great Ormond Street before finding himself a room at the end of Rochester Road in Camden Town. The next morning, at the Labour Exchange, he was given a job helping to replace the beams in the ceiling of St. Etheldreda’s church in Holborn, damaged during the blitz. During this time he was also engaged in writing and re-writing the novel that was eventually published as Ritual in the Dark.

Essentially a philosopher, he was best known for his first book The Outsider, a philosophical study of alienation in modern literature, the first of a series of seven books known as ‘The Outsider Cycle’, establishing what he called his ‘new existentialism’; but in a working life as a professional author, spanning over 55 years, he produced a startling body of work: 181 books; 600 essays and articles for a variety of magazines and newspapers; 162 Introductions to other authors’ works; and over 400 book reviews. He would often write a novel and a non-fiction work concurrently, this being his way of putting his philosophical ideas into action—very much a Continental rather than an English tradition—which goes some way to explaining why he has never been given his due credit as a novelist in his country of birth. He died on December 5th, 2013 and his body was interred in the churchyard of St Goran, near his home in Cornwall.

Page numbers refer to the 2011 edition of Adrift in Soho (Nottingham: Five Leaves Publications)

Many thanks to Pablo Behrens for permission to use his images of Soho taken in 2009: http://www.pablobehrens.com/

Adrift in Soho is has been adapted for the cinema by Burning Films: www.adriftinsoho.com – the trailer can be seen here: https://www.adriftinsoho.com/trailer/

Colin Stanley is the Managing Editor of Paupers’ Press (www.pauperspress.com), the author of two experimental novels, a slim volume of nonsense verse and several books and booklets about Colin Wilson and his work. He is the editor of Colin Wilson Studies, a series of books and extended essays, written by Wilson scholars worldwide and Around the Outsider, a volume of essays to celebrate Colin Wilson’s 80th birthday in 2011. His collection of Wilson’s work now forms The Colin Wilson Collection at the University of Nottingham, an archive opened in the summer of 2011. He now works as a freelance writer, speaker and publisher and lives in Nottingham with his wife Gail.

References and Further Reading

Sidney R. Campion, The Sound Barrier: a study of the ideas of Colin Wilson, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2011.

Sidney R.Campion, The World of Colin Wilson: a biographical study, London: Frederick Muller Ltd, 1962.

Daniel Farson, Soho in the Fifties, London: Michael Joseph, 1987.

Barry Miles, London Calling: a countercultural history of London since 1945, London: Atlantic Books, 2010.

Colin Stanley (ed), Around the Outsider: essays presented to Colin Wilson on the occasion of his 80th birthday, Winchester: 0-Books, 2011.

Colin Stanley, The Colin Wilson Bibliography, 1956-2010, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2011.

Colin Stanley (ed), The Writing of Colin Wilson’s ‘Adrift in Soho’ including Charles Russell’s ‘The Other Side of Town’, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2016.

Nicolas Tredell, Novels to Some Purpose: the fiction of Colin Wilson, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2015

Colin Wilson, ‘The Death of God’ and other plays, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2008.

Colin Wilson, Dreaming to Some Purpose, London: Century, 2004.

Colin Wilson, The Outsider, London: Gollancz, 1956.

Colin Wilson, Ritual in the Dark, London: Gollancz, 1960 reprinted by Valancourt Books (with an introduction by Colin Stanley), 2013.

All rights to the text remain with the author.