Cathi Unsworth

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

First published in 1960, Lynne Reid Banks’ The L-Shaped Room is set in a London on the cusp of radical social change. Six years after the end of rationing and three years before The Beatles first number one, the book opens on ‘a greyish sort of day’ in ‘one of those gone-to-seed houses in Fulham’, painted in shades of coffee stain, soot-smeared paintwork and the yellowish tint of creeping smog. From the first sentence, Banks vividly evokes transient, post-war, pre-Swinging West London through the medium of a cut-and-shunt boarding house with its prostitutes in the basement, chipped sinks and flickering landing lights, endless, wearisome stairs and beady-eyed landlady, Doris.

The feelings of dread and dislocation stirred by the initial observations of the book’s narrator, twenty-seven-year-old Jane Graham, are heightened by the mentions of these working girls and the memory of Doris’s gaze resting on her waistband as she shows her the crudely partitioned room of the title. Jane is in a position that no unattached career girl would want to find herself in as the Sixties began. Seven years before abortion was made legal and a year before the pill first arrived in Britain, she is one month pregnant.

This is what has brought her to the unfamiliar neighbourhood, in search of the sort of place where ‘nobody asks questions’ as Doris pointedly puts it. Having secured the tenancy of the room, Jane wanders through streets of slumped, shabby houses that seem to reflect straight back the suspicion with which she regards them through the deadeye gaze of their curtain-less windows. On learning her news, the newsagent in whose shop she found the ad for the room treats Jane to a crash-course in local manners – including his opinion of her new landlady.

“Don’t you go paying your rent on the dot, miss,” he advises. “You keep the old cow waiting, like she does me.” This sour old boy regards the ‘chippies’ in the basement as more honourable than ‘that old faggot’ Doris, with her cavalier attitude to the settlement of bills and disregard for current popular opinion on race relations. His speech is littered with references to ‘bobos’ who ‘have got to be kept in their place’, the casual deployment of which gives as tangible a feel for the attitudes of the time as the descriptive evocation of the place.

Taking pity on Jane’s obviously reduced circumstances he finally finds a little heart, directing her to his friend Frank’s café for a decent cuppa. ‘Pity they don’t divide cafés off into salon and public, if you ask me. People like to be with their own sort. Not as how you’d find many of your sort around here…’

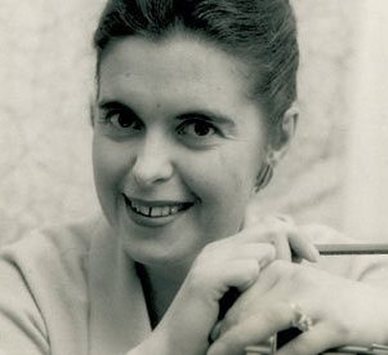

Over a comforting cup of coffee, Jane reflects on her predicament, and a life that has similarities with the author’s own. Born in London in 1929, Lynne Reid Banks was evacuated to Canada during the Second World War, returning as a teenager in 1945 to train and then work as an actress. Jane’s recollections of pre-Equity survival in rep, living off tinned spaghetti in dreary northern towns, ring with the authenticity of autobiography.

Jane’s spell as an actress came to a sorry end, which she revisits with a sense of shame, and she ended up working in a café similar to Frank’s in Yorkshire, turning the farce of her career into a kitchen sink drama in order to avoid telling her widowed father the truth. When Jane returned to London, she took up a PR job in a West End hotel. Reid Banks herself turned instead to television journalism, becoming one of ITN’s first female news reporters. She started tapping out this novel between shifts when she worked there. Throughout The L-Shaped Room, there is a brutally honest sense of self-examination in the character of Jane and her relationships with those closest to her.

For Jane now faces a familiar situation. It is her father she is running away from, a distant, awkward man, who, like most English males of his generation, has survived Depression and two World Wars without ever expressing his feelings. The combination of confessing her plight to him and the situation surrounding her own birth invoke emotions in Jane too terrible to bear.

What do you want of me father? I thought fiercely. What have you ever wanted? Not this anyway. Not a scandal, not a bastard grandchild. This won’t go far to make up for my shortcomings, like not being a son and like killing my mother by getting born.

She has already visited the sort of Harley Street doctor that could make her problem go away for the sum of sixty guineas; an experience that left Jane determined to keep the baby instead. Her father’s reaction to the news – and her own regret at the way she broke it to him, in his civil service office, in the middle of the day – have brought her to this juncture.

The room of Jane’s self-enforced confinement has been created from one much larger by the simple expediency of a partition wall. Crammed inside are a gas stove; a wash-basin doubling up as a sink; a table scarred with cigarette burns; a camp bed covered in a wartime afghan (a multi-coloured knitted blanket); a three-legged chest of drawers, a lumpy armchair and a mantelpiece adorned with two plaster Alsatians, under which resides a tiny gas fire. The Alsatians fill Jane with horror; the afghan affords her solace.

But there is more consolation than Jane had imagined to be found in the community of fellow social outcasts she discovers within Doris’s domain.

The first one she meets is a slight, dark-haired young man who ‘looks like a fledgling blackbird’. Hollow eyed and scruffily attired, acerbic and self-depreciating in equal measure, hiding his Jewishness behind his non-de-plume, Toby Coleman is the literary outsider in this world, a would-be Angry Young Man who can’t quite finish his first draft. Over the course of her months of tenancy, Jane and Toby will fall in love and then be ripped apart by the revelation of her pregnancy.

Residing on the other side of the flimsy hardwood partition to Jane is West Indian jazz guitarist John, a huge, hulk of a man with a surprisingly delicate demeanour. Jane’s first sighting of John, his black face pressed against the window of their dividing wall, terrifies her and forces her to dissemble her own prejudices. John and Toby help Jane turn her grim little abode into somewhere worth living – most memorably, when John gets rid of Jane’s bedbugs with a piece of softened soap, provoking a comical confrontation with Doris. But it is John’s bitter reaction to Jane and Toby’s affair that helps doom their relationship before it has really begun.

The tarts in the basement offer Jane a window on another forbidden world. When she makes a tentative visit downstairs, in an attempt to measure her own fall from grace against those that sell sex professionally, she finds that her older namesake Jane is not so hard-bitten as she had imagined. Both this Jane, and her Hungarian roommate Sonia, have fallen into a way of life more by accident than design. The former takes on the resigned demeanour of a hard-pressed social worker:

“Now you’re going to ask me if I hate all men. Well I don’t. You can’t hate what you don’t respect. I’m sorry for them – I don’t suppose you believe that, but it’s true… You probably think my life’s some kind of tragedy, but I’ll tell you – one of the hardest parts of it’s keeping a straight face.”

Then there is Mavis, the curious spinster on the ground floor, with her room full of knick-knacks and viperous cat. A Cockney ex-wardrobe mistress, Mavis is always listening into conversations on the hallway telephone. When she overhears Jane talking to a doctor’s receptionist, Mavis creeps up the stairs to offer her another way out of her predicament, some special pills to be downed with gin. Jane doesn’t take Mavis’ ‘remedy’ but instead gorges herself on curry, thinking that she is miscarrying when she subsequently suffers violent indigestion. After Jane recovers, Mavis cannot understand why her prescription has failed — but still cheerfully runs up baby clothes for the chastened mother-to-be.

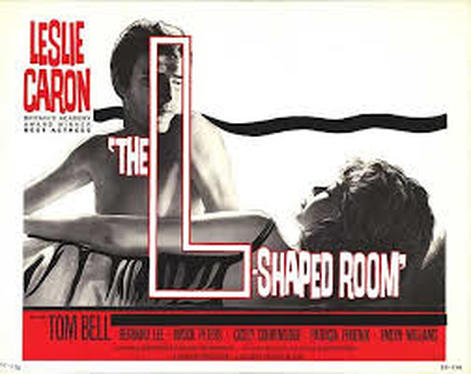

With such a beautifully rendered cast and tender exploration of societal taboo, it is little wonder that Reid Banks’ book was attractive to a film industry fired up by the work of Toby’s real life contemporaries. After John Braine’s Room at the Top and John Osbourne’s Look Back in Anger had successfully transferred to the screen in 1959, the journalist Daniel Farson coined the term ‘Angry Young Men’ to encompass contemporary literary social realism, and it’s how Jane refers to Toby in the book. These films kickstarted a cinematic new wave: Karel Reisz’s adaptation of Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning was a smash in 1960, closely followed by Tony Richardson’s production of Angry Young Woman Shelagh Delany’s A Taste of Honey in 1961. The L-Shaped Room would follow them onto the big screen in 1962, under the direction of the multi-talented Bryan Forbes.

In a recent interview with Andrew Whitehead, Reid Banks does not look back with fondness on Forbes’ movie. “Not that the characters were less interesting in the film, perhaps even more – he laid it on with a thicker trowel — but I felt them so real in my imagination that I didn’t like them being altered,” she says.

In a recent interview with Andrew Whitehead, Reid Banks does not look back with fondness on Forbes’ movie. “Not that the characters were less interesting in the film, perhaps even more – he laid it on with a thicker trowel — but I felt them so real in my imagination that I didn’t like them being altered,” she says.

While Reisz and Richardson worked closely with the authors of their source material, Forbes wrote his own adaptation of The L-Shaped Room in which several of the central characters – most notably, Jane’s father – are done away with. By casting the French actress Leslie Caron in the title role, Jane herself is necessarily altered, going by the screen surname of Fosset and not having the career that the book’s Jane does. Although Forbes cleverly picks up the ideas that float around Jane’s head in Frank’s café and gives his film version a job there instead. Meanwhile, Toby becomes a Yorkshireman – an echo, perhaps, of an Angry Young Stan Barstow or Keith Waterhouse – played by Tom Bell, an actor who nonetheless embodies the moody ambivalence of the book’s character.

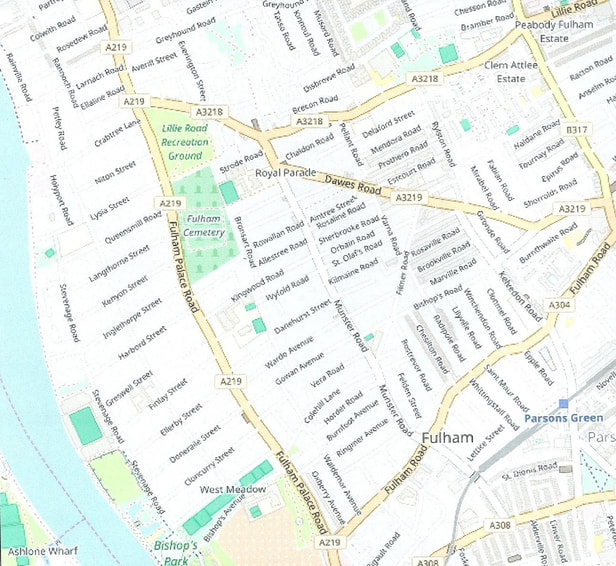

There are a couple of masterstrokes to Forbes’ vision. He relocates Doris’ boarding house from Fulham to Ladbroke Grove, which works better as a location in which class and race divides are shifting. Fulham is important in London’s black history – the Jamaican anti-slavery campaigner Marcus Garvey lived at 53 Talgarth Road from 1935 until his death in 1940, and has a nearby park named after him. It was a place of cheap lodgings – The Rolling Stones’ mouldy digs at 102 Edith Grove, where they survived the freezing 1962 winter by staying in bed all day, being a legendary example. But, the district where the book is set, around North End Road market, was predominantly white working class.

Ladbroke Grove, however, was precisely where you would have found a West Indian jazzer, an angst-ridden writer and a couple of toms competing for limited space under the same roof. Memorably described by Colin MacInnes as ‘our little Napoli’ in Absolute Beginners (1959), Ladbroke Grove was a world apart from the rest of London, where the most noticeable flux in the social mix took place. Hard to imagine now, in the post-Notting Hill world, but its towering stucco terraces, communal parks and gardens were, post-World War II, riven with bombsites; the soot-blackened houses carved up by mainly upper class landlords into slums in which they exploited successive waves of immigrants.

Incomers first started arriving to the area from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago in 1948, when, seeking to boost its post-war workforce, the British government encouraged Commonwealth citizens to settle in ‘the Mother country’. However, the Windrush generation, named for the ship that brought them into Tilbury Docks, had a very cold welcome, finding the attitudes espoused by Jane’s newsagent to be fairly entrenched. Years of resentment boiled over in the race riots of 1958, which climaxed in the streets of Ladbroke Grove.

Until the Street Offences Act came into force the year after, these same streets were also lined with working girls. In 1959, the Royal Borough of Kensington, as it was then, had the biggest population of prostitutes in all of London. Taking advantage of them were the osteopath Stephen Ward, who first introduced Christine Keeler to high society; and the serial killer Jack the Stripper, who murdered eight girls with links to the Profumo scandal between 1959-65, in one of London’s most disquieting unsolved crimes.

Interestingly, Reid Banks tells Whitehead that the room that originally inspired her to write the story was actually located in Chepstow Villas, W11, but that her decision to set the book in Fulham was based on one miserable night she spent in a boarding house there after running away from home. Chepstow Villas was slap bang in the middle of the territory of Peter Rachman, the landlord and consort of Keeler whose name is now synonymous with slum dwellings, but who was one of the very few that would allow black tenants in his properties. Original Angry Young Men writers Colin Wilson and Alexander Trocchi resided at number 24. Forbes’ location is close by – ‘Brockash Road’ is actually St Luke’s Road, across the other side of Westbourne Park Road.

Relocating to the Grove also allowed Forbes to set the pivotal scene where Jane falls in love with Toby at John’s jazz club from the West End to the sort of shebeen described in Trinidadian writer Samuel Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners (1956) and MacInnes’ City of Spades (1957). A place where all the residents of Doris’s house, and many more like it besides, come together to forget themselves over potent rum punches, delirious music and dancing. In real life, there was a jazz club on Westbourne Grove, opposite St Luke’s Road on the corner of Powis Mews. John, played by the American Brock Stevens, here plays trumpet rather than guitar. Although most of John’s scenes in the book remain intact – including the bedbug incident – there is one further major alteration.

As heavily hinted at by his fondness for needlework and cookery, John in the book turns out to be gay. In the film, it is Mavis, played to tear-jerking perfection by veteran actress Cicely Courtneidge, who hides a lavender secret. Altered from a costumier to a retired actress, her East End roots pansticked with Received Pronunciation; Courtneidge’s Mavis is a more sympathetic, melancholy character than the original. Her Christmas Day rendition of ‘Take Me Back To Dear Old Blighty’ would later be appropriated by The Smiths — those Eighties plumbers of the kitchen sink — on the opening to their The Queen Is Dead LP.

What is most poignantly missing from the film is the relationship between Jane and her father and how it is resolved, with the help of his elder sister Addy. The generation gulf between the baby boomers and their parents is another pertinent topic that Reid Banks flushes from the shadows. Like the day trip the Teenager in Absolute Beginners takes with his father to Cookham that turns into a voyage of mutual recognition, Jane and her father’s gradual awareness of each other’s fundamental humanity is the most moving aspect of all in a book shot through with compassion.

Whatever the author’s reservations, though, Forbes’ sensitive adaptation and the luminous central figure of Leslie Caron as Jane do tribute to the strength of Reid Banks’ often beautiful but never sentimental writing. The L-Shaped Room lingers far longer in the memory than later explorations of similar themes, such as Margaret Drabble’s 1965 The Millstone (adapted by her for the screen as A Touch of Love in 1969) or even Peter Collinson’s enjoyable 1968 film of Nell Dunn’s riotous 1963 novel Up The Junction. Perhaps because it forever captures that black-and-white, bomb hit and gaslit world, whose compromised inhabitants nonetheless dared to dream.

Searching for the young soul rebels

You can still furnish your bedsit and feed yourself from North End Road market, on any day of the week. Established in 1887, some stallholders are the descendants of the original costermongers – but the newsagent would be horrified at the multitude of different nationalities that have joined them since: Egyptian, Moroccan, Turkish, Filipino and Caribbean, to name but a few. Doris blazed a trail – the residents of this part of Fulham are now truly multicultural.

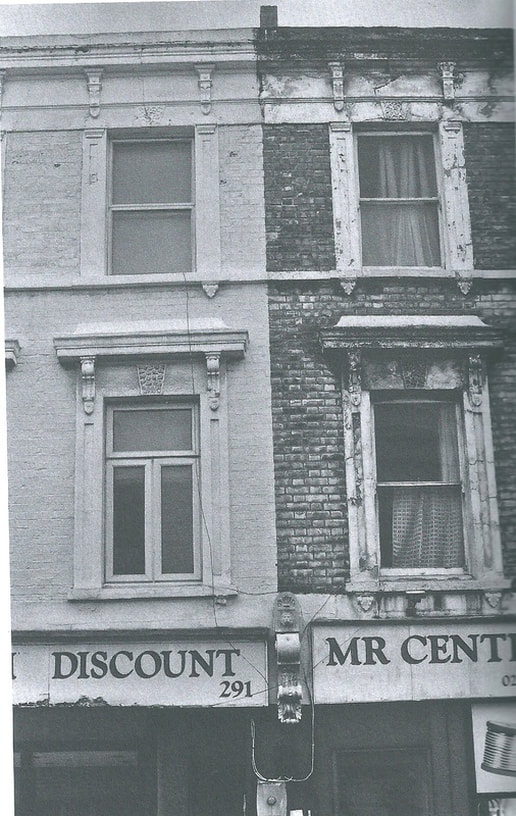

That said, the area in which the market resides, between Lillie Road and Walham Grove Road, near Fulham Broadway tube, still has echoes of the grotty old place. Pound shops, pawnbrokers and dubious fast food outlets abound – and while some of the windows may be made of UPVC these days, they retain their sinister regard.

You might yet find an L-shaped around the intersection with Lillie Road (which, charmingly, also has a junction with Munster Road). With its sagging masonry and second-hand furniture shops, this area seems to be loitering with intent.

The cinematic L-Shaped Room was on the top floor of 4 St Luke’s Road W11, adjoining St Luke’s Mews, now one of the most well-maintained properties on the street. If Doris could have held on until the film Notting Hill came out in 1999, she would have been a very rich old landlady.

Frank’s café, on the corner of Westbourne Park Road and Powis Terrace, is now The Mutz Nutz, a dressing-up outlet for dogs. Nothing could illustrate just how much the area has changed than the arrival of this, and its sister Dog Deli and Spa, on Powis Gardens. Toby would have a lot to get angry about if he was still around – not least the fact he could no longer afford to slum it in Ladbroke Grove.

Cathi Unsworth is the author of three London-based pop-cultural crime novels, The Not Knowing (2005), The Singer (2007) and Bad Penny Blues (2009), the last of which is set in a similar milieu to The L-Shaped Room. Her latest novel is Weirdo (2012). She is also the editor of London Noir (2006), a compilation of stories set within the city. All these books are published by Serpent’s Tail. For more information please see www.cathiunsworth.co.uk.

References and Further Reading

Nell Dunn, Up The Junction, MacGibbon & Kee, 1963

Anthony Frewin, London Blues, No Exit Press, 1997

Stewart Home, Tainted Love, Virgin Books, 2005

Colin MacInnes, City of Spades, MacGibbon & Kee, 1957

Colin MacInnes, Absolute Beginners, MacGibbon & Kee, 1959

Brian McConnell, Found Naked and Dead, New English Library, 1975

Anthony Richardson, Nick of Notting Hill, Harrap, 1965

Mim Scala, Diary of a Teddy Boy, Sitric Books, 2000

Samuel Selvon, The Lonely Londoners, Wingate, 1956

Tom Vague, Getting it Straight in Notting Hill Gate, Vague Publishing, 2009

Colin Wilson, The Angry Years: A Literary Chronicle, Robson, 2007

Lynne Reid Banks talks to Andrew Whitehead about the writing of The L-Shaped Room