Andrew Whitehead

London ‘is an archipelago of life’, declares Alexander Baron in the opening pages of this novel. ‘The millions of Londoners are really broken up into tens of thousands of little clusters of life. Each is gathered round some centre, perhaps a street … Within each of these little hives people live for each other as well as for themselves, and life generates a comfortable warmth.’

Rosie Hogarth is about one such little hive in the years immediately after the Second World War. Lamb Street is a respectable, inward looking working class enclave in south Islington, close to the Angel and to Chapel Market. The novel stands out for its profound sense of place. But alongside the warmth of community is the chill of exclusion. The ‘man or woman who tries to settle in London without gaining admission to one of these communities’, Baron writes in the same passage, ‘… is like a lonely traveller wandering, as night gathers, across the vast deserted moors, mocked wherever he looks by the clustering lights of villages. He is on his own, and he can go mad or die for all anybody cares.’

Baron’s novel is about Jack Agass’s readmission into the Lamb Street community where he grew up after years away at war and working abroad. Agass, a little like his creator, doesn’t easily fit – he’s not a social animal. And the war has wreaked changes in Lamb Street – and not least to the life of the woman Jack regards as his soulmate, the elusive Rosie Hogarth.

Baron’s first novel, From the City, From the Plough (1948) – was a war novel, and immediately successful. It’s a powerfully written account of the infantry man’s experience of the run up to D-day and the Normandy landings, and the spirit-sapping brutality of fighting across France. Baron himself had done just that. His second book, There’s No Home (1950), was also based on the author’s own war record – a very compassionate account of British troops billeting in a small Sicilian town, and their transient relationships with local women.

Rosie Hogarth is the author’s first London novel. The war looms large. It has left a gash in Lamb Street – a flying bomb has demolished several homes, and killed Kate Hogarth, the woman who the adopted Jack Agass ‘had grown up to worship as a mother’. That wound is being made good by the clearance of the bomb damaged houses and the building of a small block of flats – ‘it was as if they were building on a cherished grave’. Jack too – an orphan of the First World War – is wounded by the experience of war, the loss of family, and the absence of his old friend Rosie. The shadow of war hangs heavy over this book, as it did over its author.

As in his war novels, Rosie Hogarth is about an assembly of people, not an individual. Some of Baron’s later writings, and the deservedly acclaimed The Lowlife in particular, are accounts of complex and solitary characters. But in this novel, the community comes to the fore.

Alec Bernstein, as he was known until he started being published , was born in 1917, and brought up principally in Foulden Road, a plain terraced street where Stoke Newington starts to shade into Dalston. It is memorably recreated in The Lowlife (1963), and may have also partly moulded his other Jewish novel, With Hope, Farewell (1952). Visits to his grandparents in the East End helped to shape the more historical, King Dido (1969).

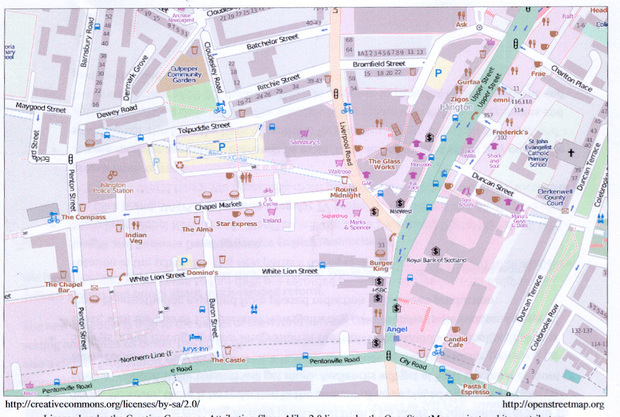

It’s not clear why Baron alighted on the Chapel Market area for his first London novel. There was no Lamb Street in this part of London. But there was, and is, a Baron Street. Perhaps the name caught the writer’s attention, or even prompted his choice of pseudonym (the family story is that he sought a shorter surname to suit the spine of a book and took ‘Baron’ from a butcher’s signboard). In any event, he locates and describes Lamb Street with some care.

It’s not clear why Baron alighted on the Chapel Market area for his first London novel. There was no Lamb Street in this part of London. But there was, and is, a Baron Street. Perhaps the name caught the writer’s attention, or even prompted his choice of pseudonym (the family story is that he sought a shorter surname to suit the spine of a book and took ‘Baron’ from a butcher’s signboard). In any event, he locates and describes Lamb Street with some care.

‘The roads that meet at the Angel are as ugly as any in the ugly sprawl of London … ‘, Baron writes in Rosie Hogarth. ‘But a hundred yards away, in the back streets, there is a quietness and serenity that keeps the traffic’s roar at bay and even holds sway over the crying of babies and the shrill chatter of women that ascends from basement windows. … It is only in the little side turnings that connect these larger thoroughfares that dirt, noise, overcrowding and the sense of haste come into their own; in each of these little streets a constant din of altercation and neighbourly intercourse echoes across the narrow pavements.’

‘The roads that meet at the Angel are as ugly as any in the ugly sprawl of London … ‘, Baron writes in Rosie Hogarth. ‘But a hundred yards away, in the back streets, there is a quietness and serenity that keeps the traffic’s roar at bay and even holds sway over the crying of babies and the shrill chatter of women that ascends from basement windows. … It is only in the little side turnings that connect these larger thoroughfares that dirt, noise, overcrowding and the sense of haste come into their own; in each of these little streets a constant din of altercation and neighbourly intercourse echoes across the narrow pavements.’

‘Lamb Street … is one of these. It consists of two short rows of two-storey cottages, once pleasantly rural, now blackened and neglected, with – at one end – a barber’s shop on one corner and a public house, “The Lamb”, on the other.’

The area on which Baron alighted was, even then, something of an anomaly amid the tight-knit localities of Finsbury and south Islington. In the year that Rosie Hogarth was published, the folklorist A.L. Lloyd described Pentonville as ‘one of the last atolls of old-time cockney life’, and commented that the streets around Chapel Market ‘have not the forlorn abandoned look of many London back streets. Something of the old elegance stays with them in the cut of a doorway or the harmony of a terrace-row. The face may be smudged but the air is still there. They are streets of character, lived in by people of character.’ [cited in Survey of London, p.14]

There is something of this still apparent in Chapel Market, which remains a defiantly down-at-heel street market where Manze’s eel and pie shop continues to do good business. The area is largely commercial and somewhat dilapidated, which has provided some protection against the gentrification so evident nearby in Barnsbury, Amwell and on the other side of Islington High Street. These streets were hit hard during the war (‘Most of the slums at the back of Pentonville Road have fortunately been removed by Hitler’s bombs, and this quarter now presents a scene of great desolation’, Harold Clunn wrote in London Marches On, 1947) and slum clearance brought further change. It paved the way for much soulless social housing to the west of Chapel Market – ‘it has to be admitted that western Pentonville is hard work’, the recent Survey of London volume for the area comments – and that has in part immunised the area against a north London middle class makeover.

There is a tenderness in Baron’s depiction of Lamb Street. He clearly cares about the people, however flawed, and relishes the environment and the culture. The novel ventures into the parlour and the bedroom, into the pub and the music hall, the workshop and the street market, the bonfire and the Arsenal match. At times, the London he describes is positively bucolic:

‘Nothing is more restorative towards life and benevolence towards the human race than a walk across London on a fine Sunday morning. The city is magically transformed. The air seems cleaner and clearer. The streets seem broader, their pavements unblemished by scurrying waste paper. … The same people walk the streets as on weekdays but their faces are no longer helots’ faces. They do not congest the streets, as on working days, in a roaring, sordid, compelled stampede but walk cheerfully and with dignity. They have an air of knowing – for a change – what they are doing, of knowing and caring where they are going, and of enjoying it all. No one is in a hurry. … It is all very beautiful: a reminder that humanity still clings to its capacity for happiness.’

There is the stamp of Gissing and of Dickens in such passages. But Baron, although conventional in the form of his writing compared to the progressive writers of the 1930s, is also entirely modern in the sense he gives of post-war adjustment and of working-class aspiration.

Jack lodges in Lamb Street with the Wakerell family and conducts a clumsy, speedy courtship with their strong-willed, sturdily built daughter, Joyce. ‘”You know what I’d like Jack?”‘, she declares as they go window shopping along Upper Street, ‘”a little house. somewhere on the outskirts.”‘ And when they later go visiting to a modern estate in Hackney, Joyce is bowled over. ‘”It doesn’t seem like London, does it? … It’s all so clean and – oh, all that grass and flowers. … it must be like living in fairyland. All sunlit. If I lived here I’d be afraid it was a dream, and that I might wake up any minute and see dirty black walls again.”‘

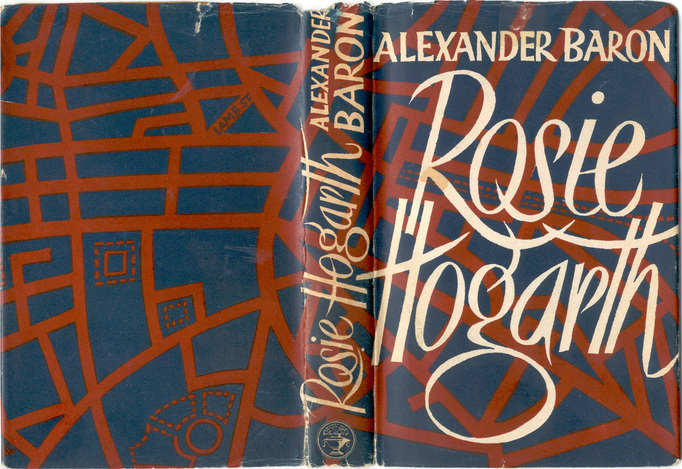

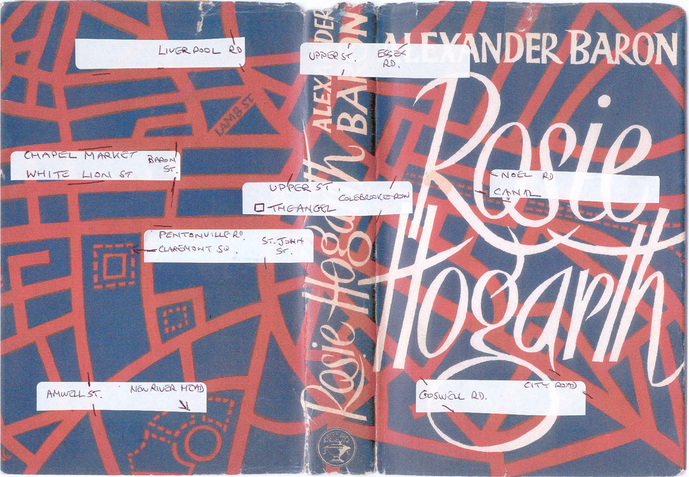

Yet, the excursions away from Lamb Street are rare. Almost all of Jack Agass’s movements are conducted on foot. This is a local London novel – a point emphasised by the original dust jacket. At first it looks like an abstract design. In fact, it’s a map, and on the rear Lamb Street is marked – the only thoroughfare given a name.

The map is entirely accurate, and is deciphered below – except in one respect. Lamb Street is shown as running between Chapel Market and Liverpool Road, not more than fifty yards or so from Baron Street. But there was no road where Lamb Street is marked – a cautionary reminder that when Baron is depicting character, or place, or incident, he borrows loosely – rather than precisely – from the people and the streets he knows. That was his method in his war novels – a composite of personal experience, others’ anecdotes and the imagined – and it’s evident in Rosie Hogarth as well.

Jack Agass is a shopfitter and so has a skilled trade. ‘Above all he sought respectability, both in his own future and in whoever was going to share it.’ The gradations within London’s working class are made most explict when Jack pays a visit to a friend in a Hoxton tenement, ‘hurrying through narrow dirty streets that were all stamped with a squalor that was foreign to Lamb Street. It was a depressing district, a disorderly huddle of big factories, blank slimy walls and monotonous rows of little houses.’

‘The great pool of poverty that poisoned the social fabric of London in the last century has almost vanished, but here and there, tucked away amid the growth of new life, noisome puddles can still be found: Bennett’s Buildings was one of them. To Jack, whose upbringing had imbued him with the outlook of that section of the working-class whose proudest possession is the word ‘respectable’, it was always unnerving to come here. The people in the ‘respectable’ streets hated these slums and their inhabitants as a reminder of their own origins and of the depths into which personal insecurity or some wrench of social change might one day plunge them again.’

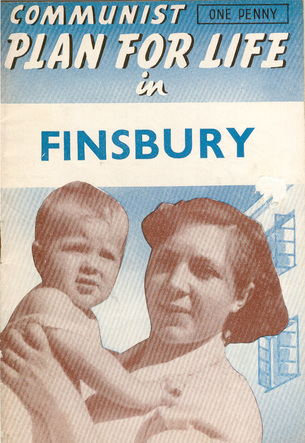

Yet the respectability of Lamb Street does not mean sobriety, nor is there much sign of the old institutions of the respectable artisan. The church porch is useful for furtive sexual encounters, but hardly anyone goes to church or chapel. There’s barely a hint of trade unions or friendly societies. The residents of Lamb Street are largely indifferent to politics. A Labour Party activist wears himself out to no obvious avail. The local communist – Mr Prawn, a retired tram conductor – is depicted as a marginal figure. There is a glancing look back to the solidarity with the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War – ‘one of those blind and beuatiful upsurges of human solidarity that sweep their class from time to time’ – but little continuing sense of political activism or involvement.

This makes the final section of Rosie Hogarth all the more unexpected and, in some ways, unsatisfactory. The title character doesn’t appear in the novel, other than as a memory of Jack’s, until almost half way through. She has moved out of the Lamb Street area and is living in a flat in Russell Square. According to street lore, she’s living a bohemian and promiscuous life, with the suggestion that she’s either selling herself or being kept as a mistress. Behind the back of his fiancee, Jack pursues Rosie. They meet several times and eventually have sex – Rosie is reluctant, but Jack is aggressively insistent. This love interest prompted lurid covers in the novel’s paperback editions.

Rosie reveals, in the closing pages of the book, that she’s not the promiscuous woman that Jack imagines. Her lifestyle is built around her furtive political allegiance – as a communist.

Rosie reveals, in the closing pages of the book, that she’s not the promiscuous woman that Jack imagines. Her lifestyle is built around her furtive political allegiance – as a communist.

‘”Many of our people work for the Government. Scientists. Senior Civil Servants. If they’re found out they lose their jobs. They have to remain undercover members. They can’t belong to Party branches, where we know that police agents are active. We can’t even bring them together in groups of their own. … So I keep in touch with each of them, separately. I meet them, discuss their problems with them, put them in touch with others where it’s essential, help them to plan their work, and above all – since they’re mostly well off – I collect all the money I can from them for the Party funds.”‘

Baron knew a great deal about the Communist Party. He had been a party member – surreptitiously, as he was prominent in the Labour Party’s youth wing – for several years, and recounts in his as yet unpublished memoirs that he trained party members in how to work underground. During the war, his links to the party weakened. But it was only after the war that he made the final, painful, break. In his memoirs, he refers to a ‘rendering of accounts’ with the party – and this novel, or at least its denouement, was probably part of that process.

It’s tempting to see in some of Rosie Hogarth’s more unsavoury utterances a glipse of the author’s own contrition for some of his own part political endeavours. She refers to Lamb Street as a ‘dreadful little street – oh, I know it’s not a slum but it’s a slum of the spirit’. Of the Communist Party, she declares: ‘I could go down on my knees and thank the Party for what it’s done for me. And I know this, too, that the harder I work to change the world for the better, the quicker I’ll change myself for the better.’

It’s tempting to see in some of Rosie Hogarth’s more unsavoury utterances a glipse of the author’s own contrition for some of his own part political endeavours. She refers to Lamb Street as a ‘dreadful little street – oh, I know it’s not a slum but it’s a slum of the spirit’. Of the Communist Party, she declares: ‘I could go down on my knees and thank the Party for what it’s done for me. And I know this, too, that the harder I work to change the world for the better, the quicker I’ll change myself for the better.’

‘We’re the first people on earth to discover the laws of history’, Rosie insists – while her father decries her ‘bloody cold, hard arrogance … like polished granite’. And he goes on: ‘you’re just a self-appointed saviour … you really think yourself better than those you want to lead’

Jack Agass is resolutely unimpressed by Rosie’s political passion. The book ends with Jack and his fiancee Joyce in their Lamb Street parlour as their wedding approaches.

‘Jack drew the curtains, shutting the lamplight, and the street noises, and the world, and the future, out of their thoughts. What was to be, they could not tell. All they knew was that, in alliance, they would always be able to make the best of a bad job. That was what made their world go round.’

As a window into Alexander Baron’s rupture with the Communist Party, the novel’s closing chapters are fascinating. As literature, they are less successful. The enduring merit of Rosie Hogarth is as a warm hearted, evocative account of a working community amid profound change – the first London novel of one of the capital’s commanding writers, and the first literary expression of his love for the city.

Further Reading

Many of Alexander Baron novels have been republished, most with introductions which discuss his life and writing:

- From the City, From the Plough, has been republished in 2019 by the Imperial War Museum

- Rosie Hogarth, published by Five Leaves

- With Hope, Farewell, published by Five Leaves

- The Lowlife, brought out by Black Spring, features an introduction by Iain Sinclair

- King Dido (Five Leaves) has a biographical note and introduction by Ken Worpole

- The War Baby was published for the first time by Five Leaves in 2019

As part of the revival of interest in Alexander Baron, Five Leaves published in 2019 the first book devoted to the author and his novels.

So We Live: the novels of Alexander Baron is edited jointly by Susie Thomas, Andrew Whitehead and Ken Worpole and also includes contributions by Sean Longden, Nadia Valman and Anthony Cartwright. It is extensively illustrated and the contents include a transcript of an interview with Alexander Baron.

There’s a website about Baron and his work and a 1999 obituary in the Guardian is also online.

The area Baron writes about in Rosie Hogarth is covered in the Survey of London, vol. 47: Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, published in 2008.

All rights to the text remain with the author.