Nuala Casey

The Years, a novel by Virginia Woolf follows the fortunes of the Pargiters, an upper-middle class London family, from 1880 to 1937. At the beginning we are introduced to Colonel Pargiter, his dying wife and the mistress he keeps in a dingy part of town. Over the course of the next few chapters we meet his children: selfless Eleanor, barrister Maurice, homely Milly, romantic Delia, academic Edward, feminist Rose and free-spirited Martin.

At first glance, The Years appears to be a family saga worthy of Galsworthy, a radical departure from Woolf’s modernist masterpieces such as Mrs Dalloway and The Waves but as you read on it becomes apparent that the author is doing something very interesting and very different here. This is Woolf’s, possibly subconscious, swansong, where she bids farewell to the present through a dreamlike journey through her past.

The novel was published in 1937 and was the last to be published in Woolf’s lifetime and though, ostensibly, it concerns itself with the fortunes of the Pargiters, The Years is, at its heart, very much a ghost story.

The novel was published in 1937 and was the last to be published in Woolf’s lifetime and though, ostensibly, it concerns itself with the fortunes of the Pargiters, The Years is, at its heart, very much a ghost story.

In 1921, Virginia Woolf published a short story called A Haunted House, which appeared in a collection entitled Monday or Tuesday. In the story, a ghostly couple walk hand in hand through their former home, floating from room to room and reminiscing about the past while the new owners are sleeping. In The Years, these silent spirits have taken flight and landed, seemingly, in Woolf’s childhood home. The Pargiter family home in Abercorn Terrace is a replica of 22 Hyde Park Gate where Woolf grew up with her father, the Victorian biographer Leslie Stephen, her mother Julia, a former Pre-Raphaelite model, her siblings Vanessa, Thoby and Adrian and step-siblings Stella, Gerald and George Duckworth.

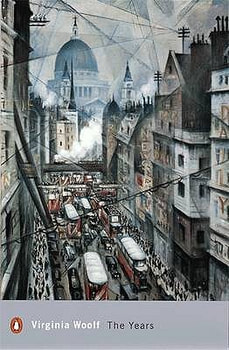

Each chapter of The Years begins with a description of the weather and a panoramic narration that takes us across fields, country lanes, rain-soaked London streets then up into the sky. There is a sense that we are hanging above whatever scene we are about to enter, taking in the view, before zooming in on a specific place: a dining room, a train compartment, a summer party.

In the country old church clocks rasped out the hour; the rusty sound went over fields that were red with clover, and up went the rooks as if flung by the bells. Round they wheeled; then settled on the tree-tops.

In London all was gallant and strident; the season was beginning; horns hooted; the traffic roared; flags flew taut as trout in a stream. And from all the spires of all the London churches – the fashionable saints of Mayfair, the dowdy saints of Kensington, the hoary saints of the city – the hour was proclaimed.

Woolf breathes life into her dead parents and siblings but it is a half-lit, translucent life; the characters float like holograms between one age and the next, never really taking shape. Woolf tantalises us with snippets of information but just when we think we are getting close to understanding Colonel Pargiter or Eleanor or Rose we are swept away up into the air before descending, bleary eyed and disorientated into another moment, another decade, a new setting and a completely different character to the one we were just torn from. And we have no choice but to begin again.

The Years was published four years before Woolf’s death and in many ways the novel reads as a departure. This is Woolf getting her affairs in order years before she stood on the banks of the Ouse with stones in her pockets. Her feet never touch the ground in this novel; her pen is raised in the air, carrying her ever upwards, as she floats above it all. The woman who loved to hike across London with the same vigour and gusto as if on a trek into the countryside; who documented those walks in Street Haunting: A London Adventure, and gave the world literature’s greatest flâneuse, Mrs Dalloway, has now taken flight.

The street walker has become airborne, traversing the skies above London like an eagle, swooping down to eavesdrop on a conversation between two of her characters, taking what carrion she needs before flying off again into the unknown.

And so it is an aerial view of London that we see in The Years and though we momentarily alight on a pavement or rest a while on the seat of an omnibus, like Woolf, we never truly feel as though we have touched terra firma. We are pulled by an invisible thread from one side of the city to the next – like Ebenezer Scrooge on his fateful Christmas Eve. One minute we are in a boarding house in a dingy Westminster back street, next we are at a lavish party in Kensington. We flit from slums to country estates to train compartments, omnibuses, halls of residences and twilit gardens but we never get to stay long enough to get a sense of the place where we have landed.

In The Years, Woolf, famous for creating a whole new form of expression in her novels through stream of consciousness prose, appears to be echoing the traditional narrators of her childhood; the great Victorian omnipresent eye from which she had spent a lifetime trying to break free. She moves from room to room, gathering objects and memories at will, reaching out for but never touching the people she has brought back from the dead. But all is not as it seems.

Woolf envisaged The Years to be ‘The Waves going on simultaneously with Night and Day.’ So the novel becomes an amalgamation of her most experimental work –The Waves – and her most conventional– Night and Day. The setting is traditional – we join the family for tea in the dining room of their London house, we see the patriarch, Colonel Pargiter, in his club – and we could easily be fooled into thinking this is a family saga of old. Yet, as you read, it becomes clear that the ground beneath is fluid; that we are paying a visit to the netherworld of Woolf’s own past. The characters shimmer across the pages like fireflies across a lake and there is a sense that if you were to reach out and touch one of them they would burst like a bubble, leaving no trace of their existence.

Through it all London looms large and omnipresent; like the father with the brilliant mind who Woolf adored; the Victorian man of letters whose death had set her free to write stories in her own way; to find new ways to express herself as only she could. As Woolf pulls us along country lanes through provincial towns where time moves slowly, she takes us further and further away from the constraints of her past and as we stand on the threshold of London we hold our breath, just like the world did in 1910, which is when, according to Woolf, the modern age began.

Even the horses, had they been blind, could have heard the hum of London in the distance; and the drivers, dozing, yet saw through half-shut eyes the fiery gauze of the eternally burning city.

For me, as a writer who draws upon London for inspiration, the city will always be one of ghosts and in The Years Woolf comes face to face with the spirit, not only of her dead relatives, but of the city she loves. It seems as though, at this point, she has removed herself from Bloomsbury and is finding solace in the London of her childhood, the city that no longer exists but one she could tap into by looking back. In a few years, World War Two would break out and Woolf’s Bloomsbury flat would be bombed to smithereens; the London she knew and loved would lie in dust and ruins and she would find there was nothing left to salvage; from her home and from the city. The only way forward would be to walk towards the river, to weightlessness and immersion in a liquid world.

When we bid farewell to the Pargiters at the end of the novel, as the family gather for a party, there are no tidy conclusions, no tying up of loose ends, we are none the wiser as to the intentions and motivations of the characters as we were at the beginning.

When we bid farewell to the Pargiters at the end of the novel, as the family gather for a party, there are no tidy conclusions, no tying up of loose ends, we are none the wiser as to the intentions and motivations of the characters as we were at the beginning.

In the mixture of lights they looked prosaic but unreal; cadaverous but brilliant. And there against the window, gathered in a group, were the old brothers and sisters.

But what we are left with is an acute sense of our own mortality and the unpredictability of life. What Woolf achieved in The Years was an exploration of the transience of time; the shimmery, unknown that all of us step blindly into each day, scratching around bewilderedly as we try to make sense of this strange life we have been thrown into unbidden. As Eleanor remarks at the end of the party:

“…all the tubes have stopped, and all the omnibuses. How are we going to get home?”

In The Years, Woolf assembles the ghosts of her past and, in doing so, loosens herself from their grip. She is free to go now; to excuse herself from the party; to step out onto the streets of the London she loved and head towards her fate. But, this time, we cannot go with her. She must make this journey alone. As we all, one day, must.

Nuala Casey was born in Stockton on Tees in 1979. After graduating from Durham University, Nuala moved to London to pursue a career as a singer-songwriter. However, her experiences living in Soho, where she chronicled the comings and goings of the people around her, took her life in a different direction. She went on to work as a copywriter and was awarded an MA in Creative Writing. Her debut novel Soho, 4am was published in 2013 and was described by the Huffington Post as ‘the London Novel revived.’ Nuala’s latest novel, Summer Lies Bleeding, was published by Quercus in August 2014 and has been described by Virginia Woolf’s great niece, the author Henrietta Garnett, as ‘a remarkable translation of The Years’, and by the Irish Examiner as depicting a London ‘that is by turns gritty and glorious.’ Urban living and the voices of the city continue to provide inspiration for her writing.

All rights to the text remain with the author.