John King

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

Political, experimental, essential – May Day, first published in 1936, is a work of fiction so sharply written its prose still excites, so relevant it could be describing events in modern day Britain. The core of the book is straightforward and familiar. The owners of an east London factory are bullying their workers into speeding up production, cutting corners to increase profit margins. The union is doing its best to fight back, considering strike action as it looks to the wider movement for inspiration. Beyond the factory gates a broader rebellion is brewing, the events that follow taking place across a three-day period leading to industrial action by busmen and a march into central London on May 1st.

Driven by author John Sommerfield’s youthful communism, May Day is clearly anti-capitalist, but it is also honest enough to look at the inner feelings of rich as well as poor. In literature, and the arts in general, then as now, the common people are stereotyped or belittled, or, if they are lucky, treated as curiosities before being dismissed to the margins. So when a novel is written from a more sympathetic position it is natural for the author to want to reverse the prejudice. Sommerfield resists the temptation. This is important, as it shows the truth that selfishness isn’t confined to capitalists, while empathy doesn’t always belong to socialists. Even so, capitalism remains the enemy, and working class characters dominate, but by considering the foibles of human nature the author earns the trust of his readership. Sommerfield believes the system is bad for everyone, that it damages exploiters as well as the exploited.

May Day’s strongest figures believe in the work ethic, that earning what you have is healthy for mind and soul. This stance is shared by the working class Seton brothers and Sir Edwin Langfier, owner of the Carbon Works. The first to appear is James Seton – communist and seaman – who is on a ship anchored off Gravesend, waiting to return to London. Soon after this we meet his brother John, sister-in-law Martine, their child and dog, sleeping in a house near the Harrow Road. John works at Langfier’s, his boss Sir Edwin a decent man who has lost his real power in a deal with Amalgamated Industrial Enterprises, a big organisation driven solely by a desire to increase profits. The paternal factory owner is being replaced by a different sort of entrepreneur. Capitalism is changing, expanding, moving towards future models.

London is present from the start: ‘The sky oozes soot and aeroplanes and burns by night with an electric glow. Railways writhe like worms under the clay, tangled with spider’s webs and mazes of electric cables, drains and gas pipes. Then there are the eight or nine million people.’ There is an almost filmic quality about many of the novel’s descriptive passages, a spliced montage of images and interaction. The industrial landscape is stark and at times brutal, but it also beautiful, tunnelling out of human inventiveness, the creation of men. All the while spring pushes through the stone and bricks of the city. Bulbs sprout. Blossom appears on trees. Nature won’t be crushed. Hope fills the pages, as the future promises new life. May Day criss-crosses the city, moving from the docks and terraces of the East End to the bustling market on Portobello Road to the green spaces of Hyde Park – and back again. Following the book’s initial release Left Review said: ‘Sommerfield gives us the true London – smelled, seen, understood’. And the story always returns to those eight or nine million souls. London is its people.

This belief in the individual shows itself in the large number of characters who make up May Day. No single voice dominates, no central character is in control. The political is made very personal as a series of smaller sketches connect to form the bigger picture. Scenes shift and faces change, but the links are neat and effective – some complementary, others adding contrast and conflict – and they always push the novel forward. This approach could easily have collapsed in on itself, the book left weak and lacking focus, but the threads are tight and can allow deviation, the final result a complex yet easy-to-read slab of true rebel fiction. John Sommerfield is brave, takes risks with his structure and prose, and it pays off. Reading the book today is like watching a disappeared London through a cut in time, standing at the bar of a grand old gin palace as familiar faces in Thirties clothes pass by outside, the windows turned into a flickering silver screen.

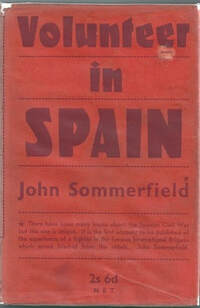

Much political fiction is dull and dogmatic, but May Day insists this doesn’t have to be the case, the experimental structure and fluency it encourages giving the book a dynamic that comes out of the author. Sommerfield lived the life – losing teeth in political punch-ups on the streets of London before going off to fight with a Republican machine gun unit in the Spanish Civil War. His friend and fellow writer John Cornford was killed in the conflict, but on his return he found that he had been reported dead, his obituary appearing in two newspapers. Sommerfield’s Volunteer in Spain was published in 1937 and dedicated to Cornford, but he felt that he had been rushed in writing it, despite mainly positive coverage.

During the Second World War, he served as an armour fitter for a Spitfire squadron, based first in Burma and then India, and while stationed near Karachi taught himself Urdu. An incident occurred at this time which shows the impression May Day had made. As a corporal and communist, Sommerfield was chosen by the other men to complain about the food being served. The officer he went to see listened and then stood up and walked over to a filing cabinet, pulled out a file and dropped it on the desk in front of him. Sommerfield was clearly known to the authorities.

He kept writing for John Lehmann’s New Writing during the war, and a new book, The Survivors, appeared in 1947. A collection of short stories that drew on his time in the RAF, it was followed by more novels in the post-war years – The Adversaries, The Inheritance, North West Five and The Imprinted, while May Day was republished in 1984. He also wrote for the Mass Observation movement, the Ministry of Information’s film unit and for various advertising companies, but May Day stands out as his greatest book.

Some readers might find May Day’s massive cast of characters and open-minded approach odd, given that Sommerfield was a member of the Communist Party when he wrote the book, but these were different days and the story captures the optimism many idealists living in Britain felt during the 1930s. The idea of a classless society seemed a real possibility in those pre-war years, while the perversions of communist rule were as yet unknown. Writing later, in 1984, Sommerfield described May Day as ‘communist romanticism’ rather than ‘socialist realism’. He goes on to call it ‘enthusiastic, simple-minded political idealism’. This is true, but idealism has to be better than cynicism, and the book is socially aware and realistic, whatever the author’s post-Stalin feelings.

When the book was republished in 1984, John Sommerfield compared living conditions with those experienced in 1936, commenting that the ‘truly rich and powerful’ carried on regardless, as if nothing had changed apart from ‘electronic improvements in the means of selling goods and bending minds’. This was long before the arrival of the internet and the ongoing digital blitzkreig, the casual doling out of easy credit and the massive levels of personal debt that followed.

To understand London and the politics of the city in the 1930s, May Day is a great place to start. The first day dawns, and the Thames is heaving with ships, the great dockyards of east London throbbing with activity, and soon we are inside the Carbon Works where ‘two hundred and forty girls in ugly grey overalls and caps live, breathe and think, their fragile flesh confused with the greasy embraces of steel tentacles’. They are on piecework rather than proper pay, and the bosses are demanding a ‘speed-up’. These young women are kept on until they are twenty-one and then let go, as their rate would have to be increased. The conditions are cramped and dangerous, and the girls are tired. Machines roar and hands are mangled.

As trouble brews, Martine is anxious about her husband, John, who – after a spell without work – has a job as a carpenter at Carbon Works. (Sommerfield also worked as a carpenter and spent periods unemployed.) Martine worries about what a strike will mean for her family. It is fine for her husband to stand up for what he believes is honourable and right, but how is she expected to feed her family? How will they live if the strike fails and he loses his job? These same arguments are prominent today. Idealism faces the realities of food and shelter, the power of the bosses and those on their payroll. May Day was written at a time of high trade union membership, before unions were hobbled by smears and legislation, and yet despite their power in the 1930s those same human concerns were obviously a factor in the life of workers. Then there is the union boss whose nest has been nicely feathered, a working man who has been corrupted and refuses to rock the boat, frustrating and alienating his members.

The fourth estate is present and correct. Long before Rupert Murdoch and Fortress Wapping, a fictional sub-editor on a leading newspaper – Pat Morgan, a former comrade of James Seton – makes his mark. Pat’s workmate is Vernon (the name of John Sommerfield’s father), a journalist – and through their work Morgan sees what the newspaper’s owner is planning to write about the busmen and their May Day protest. He visits a printer called Jackson, an older communist, and we are left with the impression that justice will be done by this man, who is a living ghost inside a propagandist’s machine.

May Day belongs to a British rebel fiction that rises up every so often before being dismissed and/or belittled – books such as Simon Blumenfeld’s Jew Boy, Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. This is ambitious, honest fiction from writers drawing on their own lives and beliefs, an English language tradition mirrored across the Atlantic in the writing of Americans such as Upton Sinclair, Hubert Selby Jr, Charles Bukowski and Thom Jones.

The 1930s were a golden period for this sort of literature, and Sommerfield was one of several young men making their mark. Just as important was the presence of publishers willing to print fiction that dealt with working class life in a realistic and honest way. These authors refused to self-censor and, for a while, reached the public in dramatic fashion. Today the likes of May Day might be regarded as ‘cult’ fiction, a term that can easily convert to kitsch and lead to casual dismissal, but this is an important book, part of a canon beyond the one inflicted on us by academics, marketing departments and the usual array of media lackeys. These writers were excited by life. Contemporaries of Sommerfield include the likes of James Curtis, Gerald Kersh, Alexander Baron and Robert Westerby.

It’s likely John Sommerfield knew Kersh and Curtis, who both drank in the Fitzroy Tavern, in north Soho, as this was one of Sommerfield’s haunts when he was in the West End. Kersh was a larger-than-life character from west London – born in Teddington, living in Shepherd’s Bush, with family links to Soho – while Curtis was from a wealthier background, his fierce socialism meaning he turned his back on the easy life, working as a hotel porter after the war. Both died broke, Curtis living alone in Kilburn, Kersh married to Flossie and dodging creditors in upstate New York. Sommerfield was more fortunate, living in and around Kentish Town after the war with his second wife Molly Moss, an illustrator who designed several of his book covers, by all accounts happy, content, optimistic. Blumenfeld, meanwhile, became a leading theatre critic for The Stage and was working until his death at the age of 97.

John Sommerfield was a pub man, the sort of character who liked a pint and chat, the company of other human beings, with firm beliefs but an open-mind. May Day comes out of the public house, the common ground where society used to meet irrespective of age, class, politics. The novel was published at a time when the General Strike of 1926 was still fresh in the collective memory, and this is referred to several times in the text, while the nature of the Carbon Works, with its female workforce stirs memories of the match girls’ strike of 1888, which took place in Bow, east London – not too far from Sommerfield’s fictional factory.

When tragedy hits the Carbon Works, it is Ivy Cutford who steps forward and finds her voice, mobilising the other girls in a doubly brave move given the position of working girls at the time. Some of the most downtrodden members of the workforce stand up and fight back. The May Day march is passing the Carbon Works… flesh meets machine… the factory gates are locked… mounted police fight the marchers… a truncheon is raised in the air. It is one of the most symbolic and dramatic passages in the book. The great workers’ posters of the period appear in the reader’s mind.

Another young woman, Jenny Hardy, has escaped the factory floor through a relationship with Amalgamated Industrial man Dartry, who has set her up as his mistress in a nice flat in a wealthy part of London. She is given money and jewellery and keeps a secret boyfriend, but Sommerfield undermines the initial dislike we feel for this married exploiter with a glimpse of his inner loneliness. Jenny wants the good things in life, lacks the dignity and morals of Ivy and her friends Molly Davis and Daisy Miller, and so the clear lines of life are blurred once more. There is a longing sitting between the lines of May Day, a realisation of the emptiness people feel when they are alone. There is a lack of love in the lives of several of the rich characters, as if a trade-off has somehow been made, and yet, interestingly, there is this same sadness in James Seton, a free spirit who has separated himself from the masses in order to fight for his beliefs.

May Day tells us about our own lives. It shows London as it was in the mid-1930s, and London as it is today. For anyone who believes in the unchanging drives of humans, the repetition of events and the lessons that can genuinely be learned from history, there are clear warnings. The book ends in an ongoing conflict between controllers and controlled on the streets of the city. The last line reads: ‘Everyone has agreed on the need for a big change.’ Those words could easily have been written today, and yet May Day, against the odds, still manages to leave us with a feeling of optimism for the future.

John King is a novelist – his latest book is Slaughterhouse Prayer (2018). With Martin Knight, he founded and runs London Books: http://www.london-books.co.uk/.

A Toast to May Day

The London of May Day is as much about flavours as specific locations, and yet the book captures local characteristics that linger to this day. The story has its roots in working class east London, but it also shows the bosses in and around Hyde Park before dipping back into the humble streets of west London. One of the joys of fiction is that the reader gets to create their own imagery, so for a version of the Carbon Works I would take a stroll around Silvertown and end up spending some time looking at the Tate and Lyle factory. Relatives of mine lived across the road long before May Day was published, their descendants then shifting into Canning Town and East Ham, and it is from these areas that the author created the factory and its workers.

There is no better place to connect with that tougher, magical London of the past than in a pub, but it has to be one that hasn’t been turned into a EuroBar and stuffed full of cloned trendies. For a taste of the old East End why not try the Salmon and Ball in Bethnal Green, across from the library and Barmy Park. This pub is friendly and down-to-earth, while many years ago it was a meeting place for Mosley’s Blackshirts, around about the time May Day was first published. John Sommerfield may well have known about the place. Another decent choice is the Pride Of Spitalfields, just off Brick Lane.

The march in May Day heads for Marble Arch, but why not stop off for a rest on the way? The Fitzroy Tavern, just north of Oxford Street, was one of John Sommerfield’s favourites, as mentioned above. With Martin Knight, I met John’s son Peter here following the London Books publication of May Day. We arranged it for midday when the pub is quiet and after a while it felt as if John was there with us – which in a way I suppose he was.

Following the First World War there seems to have been a big shift of people from east London into the new houses being built in west London. I found this in the stories of older people I knew growing up, who were born in Hounslow in the 1920s, their parents coming from Hackney, Poplar, East Ham.

So maybe east and west London aren’t as far apart as they have seemed in my lifetime, and this is reflected in the fact that one of the main characters in May Day, John Seton, lives near the Harrow Road but works at the Carbon Works. It is only really the power of the West End that divides these two sides of London.

West London comes alive on the Portobello Road, where Martine is out shopping with her son. I first went here with my father in the late 1960s as a boy, and the book’s description feels exactly as I remember the place then, even if it was written more than thirty years earlier. We watched Dave Brock – who went on to form Hawkwind and who played with and knew my dad – busking in the street. Sommerfield grew up here and the Earl of Lonsdale and the Portobello Gold are two spots where it would be worth toasting the man. After a while you might cut through time and see Martine and her son outside, and when you come back inside perhaps you will recognise the lad in the old man sitting nearby, smiling at his own memories, nursing a pint of London Pride.

John King, 2013

References and Further Reading

John Sommerfield – May Day, 1936. Republished in 1984 with an introduction by Andy Croft and an author’s note by Sommerfield. This note is also included in the 2010 London Books edition, which has an introduction by John King.

- Volunteer in Spain, 1937

- Trouble in Porter Street, 1939

H. Gustav Klaus – The Literature of Labour: 200 years of working class writing, Harvester Press, 1985

David Smith – Socialist Propaganda in the Twentieth Century British Novel, Macmillan, 1978

All rights to the text remain with the author.