Susie Thomas

Jean Rhys (1890-1979) ‘grew to hate London’. As she said in her autobiography, Smile Please, which was still unfinished at her death aged 89, London was where she had wasted her youth: ‘Ten years from seventeen to nearly twenty-seven can be a long time’. In Persuasion Jane Austen wrote: ‘one does not love a place the less for having been unhappy in it’; but Rhys may not have felt the same.

Much of 1907 to 1918 was spent in what she called, in her novel After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, ‘obscurer Bloomsbury’. This was not the avant-garde milieu of Virginia Woolf’s Gordon Square but bedsit-land hard by King’s Cross. Rhys moved briefly to Chelsea, hoping The King’s Road would cheer her up, but she soon went back to depressing Bloomsbury: ‘I felt more at home there’. During these years Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams, as she was then known, was a student at the Academy of Dramatic Arts (later RADA); a chorus girl touring the provinces; and the lover of a wealthy Englishman who lived in Berkeley Square: ‘he was like all the men in all the books I had ever read about London’. But he cast her adrift; and when she had an abortion, after an affair with another man, she began writing a diary in a room which was paid for by her first lover. She may have hated London but it gave her plenty of material.

Rhys’s early novels – After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (1930), Voyage in the Dark (1934) and Good Morning, Midnight (1939) – have always been loved by writers. Rhys was first discovered in Paris by the novelist Ford Madox Ford, who slept with her, until she grew too needy, but also helped to publish her first collection of stories, The Left Bank (1927). In his introduction he praised her ‘passion for stating the case of the underdog’ and her ‘singular instinct for form’. Since Ford promoted the careers of Ezra Pound, DH Lawrence and James Joyce among others this was quite an accolade. Rhys wrote about the end of their affair, which also involved Ford’s common-law wife, the artist Stella Bowen, in her first novel Quartet (1928): Ford appears as the powerful and chauvinistic Heidler, Bowen as the hard-bitten hypocrite Lois, and Marya, the Rhys stand-in, as the underdog. Ford probably thought this was very bad form indeed but, as VS Naipaul would later say about sexual relations in her novels, it is often difficult to tell the predator from the prey. Rhys’s husband at the time, who was in prison, was the fourth member of the quartet and to her credit Rhys translated his novel about the affair – Barred – and made sure it was published.

Rhys’s early novels – After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (1930), Voyage in the Dark (1934) and Good Morning, Midnight (1939) – have always been loved by writers. Rhys was first discovered in Paris by the novelist Ford Madox Ford, who slept with her, until she grew too needy, but also helped to publish her first collection of stories, The Left Bank (1927). In his introduction he praised her ‘passion for stating the case of the underdog’ and her ‘singular instinct for form’. Since Ford promoted the careers of Ezra Pound, DH Lawrence and James Joyce among others this was quite an accolade. Rhys wrote about the end of their affair, which also involved Ford’s common-law wife, the artist Stella Bowen, in her first novel Quartet (1928): Ford appears as the powerful and chauvinistic Heidler, Bowen as the hard-bitten hypocrite Lois, and Marya, the Rhys stand-in, as the underdog. Ford probably thought this was very bad form indeed but, as VS Naipaul would later say about sexual relations in her novels, it is often difficult to tell the predator from the prey. Rhys’s husband at the time, who was in prison, was the fourth member of the quartet and to her credit Rhys translated his novel about the affair – Barred – and made sure it was published.

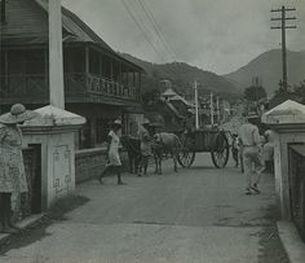

She came to England from Dominica at the age of 17. Although Rhys, like most of her heroines, was white, she was profoundly ambivalent about the colonial class into which she was born and during her childhood ‘used to long so fiercely to be black’. After a miserable time at a boarding school in Cambridge, where she was mocked for her West Indian accent, she headed for the metropolis. She transformed this experience into Anna Morgan’s story in Voyage in the Dark. Anna arrives from the Caribbean to an England she has read and dreamt about since childhood. But the city is a bitter disappointment: ‘smaller meaner everything is never mind — this is London – hundreds thousands of white people white people rushing along and the dark houses all alike frowning down one after the other all alike all stuck together –’. Rhys wasn’t part of literary Bloomsbury but she knew all about stream of consciousness. Anna thinks ‘I’m not going to like this place’ and she’s right.

There must have been plenty of reasons not to like London during this period, particularly because of its treatment of foreigners. Racism is most obviously ugly in Good Morning Midnight. When Sasha meets an impoverished Russian painter in Paris he tells her about his encounter with a woman in Notting Hill Gate who accosted him on the stairs of their boarding house:

She came from Martinique, she said, and she had met this monsieur in Paris […] Everybody in the house knew she wasn’t married to him, but it was even worse that she wasn’t white. She said that every time they looked at her she could see how they hated her […]. At first she didn’t mind – she thought it comical. But now she had got so that she would do anything not to see people. She told me that she hadn’t been out, except after dark, for two years. […] I said: “But this monsieur you are living with, what about him?” “Oh, he is very Angliche, he says I imagine everything.” […] I said to her: “Don’t let yourself get hysterical, because if you do that it’s the end.” But it was difficult to speak to her reasonably, because I had all the time this feeling that I was talking to something that was no longer quite human, no longer quite alive.

The dehumanising horror is made particularly painful by its understated Englishness, but it can all be dismissed as the woman from Martinique’s imagination.

Racism is also central to ‘Let Them Call it Jazz’ in which the West Indian woman gets to speak for herself. The story begins in a boarding house in Notting Hill Gate: ‘Don’t talk to me about London. Plenty people there have heart like stone’. When her savings are stolen, the narrator, Selina, ends up in a damp and empty house in the suburbs. Rhys was probably drawing on the period when she lived in Beckenham, where she was often alone: ‘English people take long time to decide – you three-quarter dead before they make up their mind about you’. Selina gets drunk, sings too loudly in the garden, and the neighbours complain. In retaliation she throws a brick through their window – rather like Rhys, who was remanded in Holloway prison after assaulting a neighbour. (Rhys found herself in front of Bromley magistrates 8 times between 1945 and 1950) While she is in Holloway, Selina hears a fellow prisoner singing in ‘a smoky kind of voice’ from the punishment cells: the song tells the girls ‘cheerio and never say die’. Once she’s out of prison Selina whistles the Holloway song at a party in London. A musician hears it, pretties it up, and makes a packet. She lets ‘them play it wrong’, even though that song was all she had, because she is no longer a victim: ‘I’m not frightened of them any more – after all what else can they do?’ It’s a long time until the voice of a Caribbean woman is heard again in London fiction.

Students often find Rhys’s female characters infuriatingly old-fashioned: “Why are they so dependent on men? Why don’t they get a job?” Rhys herself was hopelessly passive, except as an artist, when she was steely and precise; but writing is the one thing her heroines don’t do. In After Leaving Mr Mackenzie Julia discusses life, literature, and Dostoievsky with her solidly respectable Uncle Griffiths. He says: “Why see the world through the eyes of an epileptic?” And she replies: “But he might see things very clearly, mightn’t he? At moments.” Uncle Griffiths also believes that everyone has to “sit on their own bottoms”. Since Julia has come home a failure she must expect to pay the price of the rebel: a cold shoulder from the family. Once Uncle Griffiths suspects that Julia might ask for a loan he suddenly develops an imagination, envisaging all the ways he could become a pauper. Rhys’s novels may have a ‘one-eyed aspect’ but, as VS Naipaul appreciated, her themes engage us more than ever today: ‘isolation, an absence of society or community, the sense of things falling apart, dependence, loss.’

After Leaving Mr Mackenzie begins in Paris, six months after Julia has parted from her lover and is hiding in a hotel room with a book and a bottle waiting for the ‘sore and cringing feeling to pass’. A letter arrives from Mr Mackenzie and his lawyer stating that her weekly allowance will be discontinued: ‘The two perfectly represented organized society, in which she had no place and against which she had not a dog’s chance’. She decides on a whim to go back to London, hoping for some kind of enlightenment, which she doesn’t find. In the third part Julia returns to Paris, but it’s a downward spiral. Good Morning Midnight is a mirror image: London, Paris, London. Orwell overlooked women in Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) but Rhys would have agreed with him: ‘It’s fatal to look hungry. It makes people want to kick you.’

Oddly, Naipaul believed that Rhys ‘avoided geographical explicitness’; that she never ‘set’ her scene anywhere. (Ford too complained of a lack of local colour in her Left Bank stories.) Perhaps this is because there is often a dream-like (or nightmarish) quality to her settings. To Julia ‘London was a cold and terrifying place’: ‘It was the darkness that got you. It was heavy darkness, greasy and compelling. It made walls around you, and shut you in so that you felt you could not breathe. You wanted to beat at the darkness and shriek to be let out’. Although the setting seems vague the topography is always specific:

She walked on through the fog into Tottenham Court Road. The houses and the people passing were withdrawn, nebulous. There was only a grey fog shot with yellow lights, and its cold breath on her face, and the ghost of herself coming out of the fog to meet her.

Julia, like all Rhys heroines, is precariously lodged. She starts out in a shabby hotel in Arkwright Gardens in Bloomsbury before moving to a boarding house in Notting Hill; she hides in her room and hardly believes it is worth the effort to look for love in London; it is not a city that is kind to women. London for Rhys is sinister and soulless; the endless rows of houses ‘frown down’ on her heroines, who suffocate in the city for as long as they can stand it, and then escape to Paris. Julia has no home and no friends; hers is an utterly alienated vision of the city:

These streets near her boarding house on Notting Hill seemed strangely empty, like the streets of a grey dream – a labyrinth of streets, all exactly alike.

She would think: “Surely I passed down here several minutes ago.” Then she would see the name Chepstow Crescent or Pembridge Villas, and reassure herself. “That’s all right; I’m not walking in a circle.”

The ‘grey dream’ and ‘the labyrinth’ are recognisable evocations of London but they are also images of Julia’s emotional confusion and deadness, which in turn seem to be produced, or at least reinforced, by the city itself. In Paris she veers wildly between euphoria and drunken despair, but in London she seems disembodied and ghostly. Julia thinks ‘London tells you all the time, “get money, get money, get money, or be forever damned.” Just as Paris tells you to forget, forget, let yourself go’

In Rhys’s London sexuality is hygienic and respectable, taking place behind the doors of family houses, from which she is barred; or furtive and under cover of darkness. Mr Horsfield, Julia’s lover, creeps up the stairs of her boarding house at night, tells her ecstatically that she has ‘given [him] back [his] youth’, but in the daylight he is ashamed of his attraction to her and sneaks off leaving a note. They had first met in a café in Paris, where Rhys’s lovers usually meet. Perhaps because Dominica was once a French colony, Rhys’s fictional West Indies always seems more French than English; and perhaps because she loved Dominica, she was always nostalgic about Paris. She didn’t seem to be enamoured of the literary Left Bank of the 1920s: perhaps Henry Miller and even Hemingway sounded like “jazz” to her. Certainly she was as much an outsider on the Left Bank as she was in literary Bloomsbury. But in her fiction Parisian cafes provide a space for romantic encounters in a way that London pubs rarely do. The city also changes how men feel. In Paris Julia’s reserved English lovers allow themselves to be carried away by their emotions: ‘Paris had attracted [Mr Mackenzie] as a magnet does a needle’. Mr Horsfield is ‘momentarily freed from self-consciousness’ in Paris, in a way he has longed for, but in the end he returns to his mews in Holland Park: ‘a world of lowered voices, and of passions, like Japanese dwarf trees, suppressed for many generations’. Her Englishmen are frightened of feeling too much: they want sex and to indulge in a little sentimentality about Julia as a representative of the insulted and injured. But they always revert to their cautious code and she is never on first name terms with them.

At the heart of the novel is the paralysed figure of Julia’s mother, who is dying in Acton: the suburban sick room ‘smelt of disinfectant and eau-de-Cologne and rottenness’. Julia hopes ‘she would learn many deep things’ at her mother’s bedside but instead she is left ‘bewildered’ by her death ‘as though some comfort that she thought she would find there had failed her’. Although Julia provides the novel’s main point of view, the third person narration allows Rhys to show what happens to the good girl, Julia’s sister, who has taken care of their invalided mother for years: ‘Everybody had said: “You’re wonderful, Norah.” But they did not help’. Norah keeps a copy of Conrad’s Almayer’s Folly by her bed and identifies with the female slave, who ‘had no hope, and knew of no change’. Even though Julia knows what her sister has endured she makes a terrible scene after the funeral. Flaring up with the rage of the outsider she screams: “If all good, respectable people had one face, I’d spit in it.” Understandably, Norah’s friend Miss Wyatt and Uncle Griffiths, turf Julia out.

Rhys’s first novels enjoyed a succes d’estime but after WW2 they sank into oblivion. She lived in semi-poverty in the West Country (first in ‘Bude the Obscure’ and later Devon) and was not published again until 1966, when Wide Sargasso Sea established her as a major figure in postcolonial literature. In the nearly thirty years between Good Morning, Midnight and her rewriting of Jane Eyre from the point of view of the Creole Madwoman in the Attic, she was presumed dead and then rediscovered, until she felt as if she had been ‘killed off more times than Rasputin’. Francis Wyndham, and Diana Athill, who became her editor and friend, masterminded her literary rehabilitation. Rhys won the Royal Society of Literature Award at the age of 76, but as she said, recognition came ‘too late’. In her final years the novelist David Plante worked with her on Smile Please and later recalled their friendship in his book Difficult Women.

It is easy to be seduced into reading Rhys’s fictions autobiographically. But despite the similarities between (Ella) Rhys and Anna, Marya, Julia, Sasha and Selina, they are personae. As Rhys said: ‘a novel has to have shape and life doesn’t have any.’ Although she was scrupulous about getting it right, it was the truth of experience rather than documentary fact that interested her. Rhys’s mother died in Dominica but in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie the mother dies in suburban Acton, in exile from Buenos Aires and ‘sickening for the sun’: it is the perfect location for the miserable end of a woman labelled ‘middle class, no money’; and probably the ending that Julia fears the most. In After Leaving Mr Mackenzie Julia looks back on her first affair, with Mr James, which ended when she was 19, and wonders if she hates him: ‘Because he has money he’s a kind of god. Because I have none I’m a kind of worm.’ But in Smile Please she remembers her first lover in Berkeley Square and thinks ‘What a very kind man he must have been’.

In Rhys’s fiction there is nowhere for a single woman to go in London after dark except the cinema and a Lyons’ tea-shop. In fact women crowded into pubs, clubs and cafes as Rhys knew: in her autobiography she recalls that she ‘went to the Crabtree nearly every night and stayed till breakfast time’. The Crabtree was a club on Greek Street in Soho, founded by Augustus John among others, and frequented by Jacob Epstein. It was packed with people dancing and singing. Looking back at London on the eve of WW1 she remembered: ‘There were nightclubs all over London, all sorts, all prices, and all full of an excitement that I had never known before and people dancing the Destiny waltz.’ But that isn’t the city she shows in her fiction.

In Voyage in the Dark Anna discovers a poem in a drawer which was left by a previous tenant, who was chucked out because he couldn’t pay the rent: ‘Loathsome London, vile and stinking hole’. Then, as now, it is a city of repression, racism, and misogyny, which isn’t kind to people without money. But, between the cracks, there was/is still space to have fun.

Jean Rhys’s London

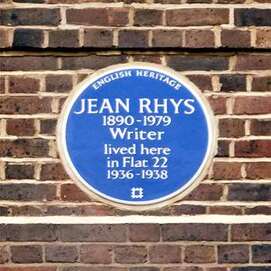

In 2012 a blue plaque to Rhys was unveiled outside Flat 22 in Paultons House, Paultons Square, Chelsea, where she lived for two years (1936-38) with her second husband, and wrote Good Morning, Midnight in bed.

Most readers associate Rhys with Bloomsbury: her heroines are lodged in rooms off the Gray’s Inn Road, Arkwright Gardens and Judd Street; in Smile Please Rhys fondly recalled the boarding house in Torrington Square, where she lived in 1917, and where she was ‘the only English, or pseudo-English, person’.

Although Chelsea is not the most obvious place to commemorate Rhys as a London writer it is probably the only stable address she had. ST

Further Reading

Carole Angier, Jean Rhys: Life and Work, Faber and Faber, 2011 (first published 1990).

Diana Athill, Stet: An Editor’s life, Granta, 2000. This has an excellent chapter on Jean Rhys.

V.S. Naipaul, “Without a Dog’s Chance”, review of the reissue of After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, The New York Review of Books, May 18, 1972.

Jean Rhys’s writing:

- The Left Bank: sketches and studies of present-day Bohemian Paris, Cape, 1927. The stories Rhys wished to preserve are included in Tigers are Better Looking

- Quartet, Penguin Classics, 2000 (first published as Postures 1928)

- After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, Penguin, 1971 (first published 1930)

- Voyage in the Dark, Penguin, 1969 (first published 1934)

- Good Morning, Midnight, Penguin, 1969 (first published 1939)

- Wide Sargasso Sea, Penguin Classics, 2000 (first published 1966)

- Tigers are Better Looking, Penguin, 1991 (first published 1968). Contains “Let Them Call it Jazz”

- Sleep it Off Lady, stories, Penguin, 1987 (first published 1976)

- Smile Please: an unfinished autobiography, with a foreword by Diana Athill, Penguin, 1984 (first published 1979)

And if you want to hear Jean Rhys’s voice, this site includes audio recorded towards the end of her life.

All rights to the text remain with the author.