Anne Witchard

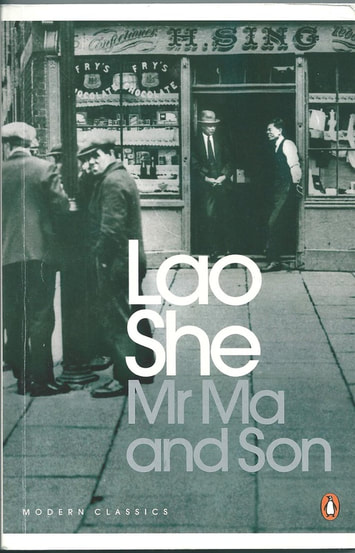

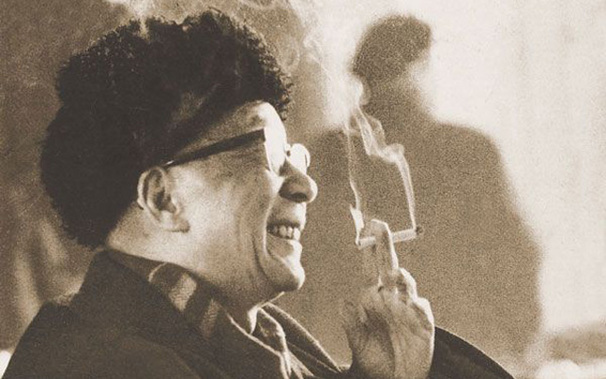

Lao She is one of the most important Chinese writers of the last century, perhaps best known to English readers for his great proletarian classic Rickshaw Boy (1937). Now an earlier and little known novel, Mr Ma and Son: Two Chinese in London (Er Ma 1929) has been published by Penguin Classics in an excellent translation by William Dolby that at last does justice to Lao She’s unsung comic masterpiece. Mr Ma and Son gives us a unique account of what life was like for Chinese people in 1920s London. The novel draws largely on the writer’s own experiences, since his arrival in 1924 to take up a post teaching Mandarin classes at the School of Oriental Studies, then at Finsbury Circus.

The novel’s two main protagonists are the father and son of its title; widower Mr Ma and his son, Ma Wei. Mr Ma senior is a relic of the old Imperial China, fixated by notions of the refined life of a Mandarin: ‘nothing good would come of trade and earning one’s money by one’s own sweat and blood’ he believes. Ma Wei, by contrast, is a typical young man of post-revolutionary China who aspires to achieve a better society. They have come to London because Mr Ma’s brother has bequeathed them a curio shop near St Paul’s. The adventures of father and son as they gradually adjust to a confusing new world provide us with a Chinese perspective on an encounter which has otherwise been one-sided and generally skewed by the Yellow Perilist bias of the era.

English novels, plays and films of the 1920s are notable for their offensive stereotypes of the Chinese. Inevitably this had pernicious effects on the lives of Chinese people living in London. ‘Some of us’, wrote Chiang Yee in The Silent Traveller in London (1938), ‘keep apart in a dull way; some refuse to mix in circles where they would be asked many difficult questions arising from popular books and films on Chinese life.’

English novels, plays and films of the 1920s are notable for their offensive stereotypes of the Chinese. Inevitably this had pernicious effects on the lives of Chinese people living in London. ‘Some of us’, wrote Chiang Yee in The Silent Traveller in London (1938), ‘keep apart in a dull way; some refuse to mix in circles where they would be asked many difficult questions arising from popular books and films on Chinese life.’

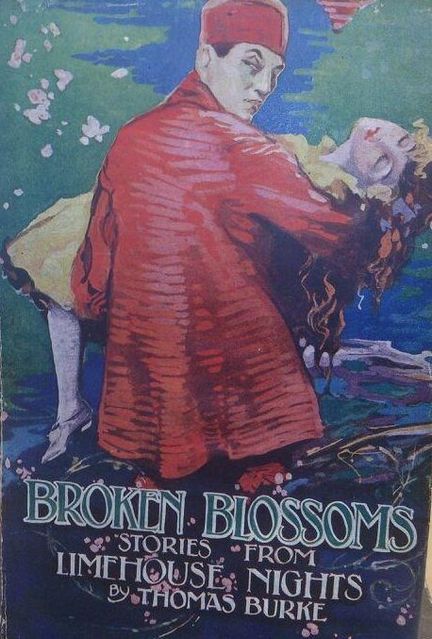

The writer Xiao Qian noted that in England ‘it was difficult to find a barber willing to cut the hair of an Oriental, and renting a room was virtually impossible’. Despite these testimonies, of all the Chinese who came to England during the inter-war years, Lao She was the only one to directly confront the popular Sinophobia endemic in British society. Written principally for a Chinese readership Mr Ma and Son portrays the pernicious effects of the media on the lives of overseas Chinese. A wake-up call for China of the period, today the novel gives us a rare if not unique picture of the social and commercial affairs of the shopkeepers, café proprietors, and seafarers that made up the major part of London’s small Chinese community, then based in Limehouse in the East End.

Lao She’s mordant wit is at work from the moment his Chinese protagonists disembark at English Customs, the officers’ ‘imperial superiority fully on parade’. He sets the tone of the novel with a wry comment on the bedeviled history of Sino-British intercourse. The Mas’ suitcases reveal just some canisters of tea and Mr Ma’s silk gowns: ‘Fortunately as it happened’ old Mr Ma and his son Ma Wei ‘brought neither opium nor weapons with them’. Cleverly positioned in socio-geographical terms, the Mas’ shop near St Paul’s bridges the gulf between Bloomsbury and Limehouse and the two different classes of Chinese in London. The Mas, like the many Chinese students in London, take rooms in one of the small lodging houses near the British Museum’ which ‘are prepared to let rooms to Chinese, not because people in this area have uncommonly kind hearts but because they thrive on living off Orientals so make the best of being obliged to deal with a bunch of yellow-faced monsters’. Young Ma Wei ventures into London’s Chinatown – as Lao She did himself – to eat pork noodles and egg fried rice at the Chinese cafés in Limehouse Causeway. The description of the Top Graduate Bower in Mr Ma and Son gives us a picture of the ‘types’ who frequented London’s Chinese restaurants while making a sardonic comment on international relations and English attitudes to China:

It’s roomy, the food’s cheap, and at all hours it gives the impression that all the great minds and worthy nobility of the world are gathered there. Not only do Siamese, Japanese and Indians frequent it for their

meals, but even English people, impecunious artists, members of the socialist party—sporting red ties—and fat old ladies—in quest of the quaint—often go there for a cup of Lung-ching tea, or a bowl of chop-suey.

As they navigate the districts of London and the social conventions of English society, the Mas find that their presence arouses mixed responses –academics are curious, shopkeepers are suspicious, the Reverend Ely and other ‘old China hands’ are patronising. The Mas’ relationship with their landlady Mrs Wedderburn and her hostile daughter Mary forms the crux of the novel. The small-minded London landlady, a fixture of British fiction of the period, is as gently deconstructed as are the foibles and pretensions of the elder Mr Ma. Landlady types in British interwar fiction typically include spinsters struggling to keep up appearances on limited incomes or widows trying to make ends meet in a manner to which they were formerly accustomed. The real-life Misses Parrot, with whom Lao She first boarded in their semi-detached house at 18 Carnarvon Road, in north London’s outer suburb of Barnet, fit the former description, and the Mas’ Bloomsbury landlady, Mrs Wedderburn, the latter. Lao She’s experience was that ‘Landladies’ daughters often become the wives of Chinese students studying abroad.’ Most significantly he recognized that ‘this is the stuff of which novels are made’.

Ma Wei’s treatment by his landlady’s daughter, a focus of frustrated romantic attention in literature from William Hazlitt’s Liber Amoris (1823) to Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955), is informed by her exposure to popular media images of the Chinese.

If there were no more than twenty Chinese people dwelling in Chinatown, the accounts of the sensation-seekers would without fail magnify their number to five thousand. And every one of those five thousand yellow-faced demons will smoke opium, smuggle arms, commit murder – hiding the corpses under the bed – rape women – regardless of age – and commit an endless amount of crimes.

Ma Wei is fixated by Mary Wedderburn’s legs and the shortness of her skirts while he is bemused in general by the devil-may-care lives of people in England, young and old alike:

Ice skating rinks, circuses, dog shows, chrysanthemum shows, cat shows, leg shows, car-races, grand contests and special competitions … The English could never have a revolution with so much to look at and talk about, who’s ever got the time for a revolution.

His father’s confusion over the whimsicalities of foreign devils, especially female ones, is a chief source of humour in the novel. Lacking Ma Wei’s acute sensitivity, he manages to integrate more easily with his English hosts. That summer all the girls are wearing broad brimmed straw hats adorned with ‘all kinds of wonderful falbalas—embroidered purses from Old China, china dolls from Japan, ostrich feathers and huge daisies’. Mr Ma paints the Chinese character for ‘beautiful’ which Mrs Wedderburn copies in embroidery onto Mary’s hatband. ‘Mary’s hat band embroidered with a Chinese character is sure to cause a hat revolution’ Mr Ma thinks proudly, only to be doubled up in silent hilarity when he sees that Mrs Wedderburn has sewn it on upside down and the character now reads ‘big bastard’.

Flapper fashions, cafés and pubs, sports and dating, the preoccupations of everyday Londoners, quickly become part of life for the two Mas. Lao She’s feelings about the English were nothing if not ambivalent. His novel critiques their arrogance, unsociability, racial and class discrimination and narrow-minded patriotism. Reverend Ely’s son Paul ‘come rain or shine will go and watch football or hockey, or anti-Chinese films and was fully capable of standing for three hours in the rain, waiting for a glimpse of the Prince of Wales’.

The prevailing climate of racial prejudice in 1920s London was described by the Black American poet, Claude McKay, as being ‘as suffocating as the fog which not only wrapped you round but entered your throat like a strangling nightmare’. The welcome given to those who had come from all corners of the Empire to assist the war effort had dried up as the job market diminished and economic depression loomed. Race riots in Limehouse and other parts of Britain had been followed by further restrictions to the Aliens Act in 1920 and 1925, designed to repatriate and restrict entry of ‘coloured’ subjects, events which are addressed in the novel.

The denouement comes from an event contemporaneous with Lao She’s last year in London, the making of the film Piccadilly (1929) scripted by Arnold Bennett and recently restored to some acclaim as a vehicle for Anna May Wong. The complicity of Chinese as paid extras in stage productions and films such as Piccadilly was an issue that concerned Chinese students who fruitlessly petitioned the Lord Chamberlain against demeaning representations of Chinese people. In March 1928, W. C. Ch’en (Chen Weicheng), the Chargé d’Affaires at the Chinese Legation, made an official complaint to the Foreign Office that no less than five plays currently showing in the West End represented Chinese people in a ‘vicious and objectionable form’. Lao She’s exploration of the damaging consequences of their effects on the psyche of his young protagonist, Ma Wei, expressed chiefly through his ill-starred passion for Mary Wedderburn, bears comparison with other London novels of the period.

The introspective alienation of Ma Wei and the mapping of the social topography of the city is as nuanced as that of those seminal works of metropolitan modernism, Aldous Huxley’s Antic Hay (1923) and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925). Rather than show London in the sepia-toned gloom commensurate with the lovelorn mood of Ma Wei, his misery is heightened by the cheeriness of his surroundings. The flower beds of Hyde Park and Regents Park are packed with blooms at all seasons: ‘deep red fuchsias’ jostle with ‘pale blue hydrangeas laughing in the sun’. Even the moving lines of traffic are rainbow tinted, the cars in town are ‘gay and colourful, nipping around so neat and nimble-oh in the sunshine with a distinctly blue hue to the smoke that they were puffing from their tails’. Lao She’s London is a city of gay flowers, scarlet uniforms, polished brass door knockers, striped awnings and rosy-cheeked girls, a city where determined commerce and hedonism contest with post-war neuroses and despair.

Anne Witchard is a senior lecturer in English Literature at the University of Westminster. She is the author of Lao She in London, published by Hong Kong University Press in 2012, and of Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights and the Queer Spell of Chinatown (Ashgate, 2009). She wrote about Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights in London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White and published by Five Leaves in 2013.

Further Reading

Lao She’s Mr Ma and Son, translated by William Dolby and with an introduction by Julia Lovell, was published by Penguin Modern Classics in 2013

Anne Witchard’s Lao She in London is published by Hong Kong University Press

All rights to the text remain with the author.