Ged Pope

‘Chaos and barbarism once more reigned supreme even in Regent Street’.

Aldous Huxley’s second novel Antic Hay (1923) is a brilliant portrait of twenties London.

The novel is part of a tradition of post-war writing that presents the traumatised capital as being somehow both dead and empty and full of frenzied, pointless activity. In T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), Michael Arlen’s The Green Hat (1924),D. H. Lawrence’s novella ‘St Mawr’ (1925), Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925), Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies (1930) and Jean Rhys’s After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie (1931), we see a numbed, fragmented London, full of ghosts and echoes of the recent dead.

Antic Hay focusses on the jarring disconnections created by a civilisation now without moorings, its long-cherished beliefs, morals, and culture destroyed in the war. Religion is reduced to shabby spiritualism. Idealism is laughable. Above all, High Culture, that mark of superior civilisations, has lost its aura. The novel is packed with numerous untranslated fragments of Greek, Latin, Italian and German quotes, with references to Virgil, Catullus, and Horace, to Dante, to Michelangelo and Domenichino, to Alberti and Borromini, to Mozart. Yet this is all insignificant: post-Great War London is filled instead with the clamour and intensity of modern things, all the ‘the mauve electric moons’ of a hectic consumer culture. We have accounts of jazz and popular hits, of frenetic dancing, drinking and drug-use, casual sex, and West-End shopping and garish advertising (the bright neon of Piccadilly frequently reappear). The novel’s advertising guru, Mr Boldero, sums it all up: “They swallow what’s given them…. Cinemas, newspapers, magazines, gramophones, football matches, wireless, telephones — take them or leave them, if you want to amuse yourself”.

Antic Hay focusses on the jarring disconnections created by a civilisation now without moorings, its long-cherished beliefs, morals, and culture destroyed in the war. Religion is reduced to shabby spiritualism. Idealism is laughable. Above all, High Culture, that mark of superior civilisations, has lost its aura. The novel is packed with numerous untranslated fragments of Greek, Latin, Italian and German quotes, with references to Virgil, Catullus, and Horace, to Dante, to Michelangelo and Domenichino, to Alberti and Borromini, to Mozart. Yet this is all insignificant: post-Great War London is filled instead with the clamour and intensity of modern things, all the ‘the mauve electric moons’ of a hectic consumer culture. We have accounts of jazz and popular hits, of frenetic dancing, drinking and drug-use, casual sex, and West-End shopping and garish advertising (the bright neon of Piccadilly frequently reappear). The novel’s advertising guru, Mr Boldero, sums it all up: “They swallow what’s given them…. Cinemas, newspapers, magazines, gramophones, football matches, wireless, telephones — take them or leave them, if you want to amuse yourself”.

The novel’s central core of affluent London bohemian aesthetes, critics, painters, poets and socialites are frenzied and fragile, depressed and lost, bored and infantilised, above all are acutely aware of being inauthentic fakes. A generation gap (possibly the first) appears, and new urban types emerge: Flappers, leisured women free to roam the city, independent female upper-class socialites, advertisers, quacks, faddists and scammers, entrepreneurs exploiting urban trends.

Permanence and tradition are replaced by restless frenetic movement. The novel’s title is taken from Christopher Marlowe: ‘My men like satyrs grazing on the lawns/Shall with their goat-feet dance the antic hay’. Dance here, in that Jazz Age decade of frenzied dance-crazes (and there is a great scene in a jazz club based on the infamous dive Cave of the Golden Calf, at 9 Heddon Street) is desperate, repetitive movement, constant dynamism, a desire to keep moving, to never stop.

It is this nonstop movement makes Antic Hay one of the great London novels as we are treated to numerous detailed descriptions of West End locations, streets, bars, restaurants, and nightclubs, as its ghastly crew of dissatisfied and grotesque artists, litterateurs, rakes, toffs, and socialites pointlessly bound around town. They are all skating over an abyss here, and only reckless movement, and desperate partying and sex, fend off the dreaded sense of meaninglessness, boredom or accidie. There is no flânerie here, no profound engagement with the city. They take the city at speed, distracted, self-obsessed, in fact really preferring to drive.

Let us follow, then, this disparate cast of characters on just some of their adventures as they ping around the West End in the early summer of 1922.

The novel opens with the novel’s kind-of central character Theodore Gumbril Junior (this being satire, all characters have oddly self-describing names, or aptronyms). While sitting on a hard wooden bench in the school chapel where he unhappily teaches, spiritual thoughts are overtaken by a profounder epiphany, an insight that will profoundly change humanity for ever: inflatable rubber inserts for trouser-seats. Gumbril immediately resolves to quit his dreary job, move to the metropolis, and develop, advertise, and sell his revolutionary pneumatic ‘Gumbril’s Patent Small-Clothes’.

Gumbril’s first port of call in London is his dad’s house: ‘Gumbril Senior occupied a tall, narrow-shouldered rachitic house in a little obscure square not far from Paddington’. The past here is decrepit, crumbling, moth-eaten. Yet Gumbril Senior, an architect, presents one of the few centres of calm and order in the novel. He has a collection of architectural models, all exemplars of Classical tradition of order, proportion and rationality; ‘When I think of Alberti…of Brunelleschi… and when of Michael Angelo’. He also has a huge model of a beautiful city that Gumbril Junior fails at first to recognise: “What is this? The capital of Utopia, or what?” It turns out to a model of Wren’s elegant great plan for a post-Great Fire London, never built of course.

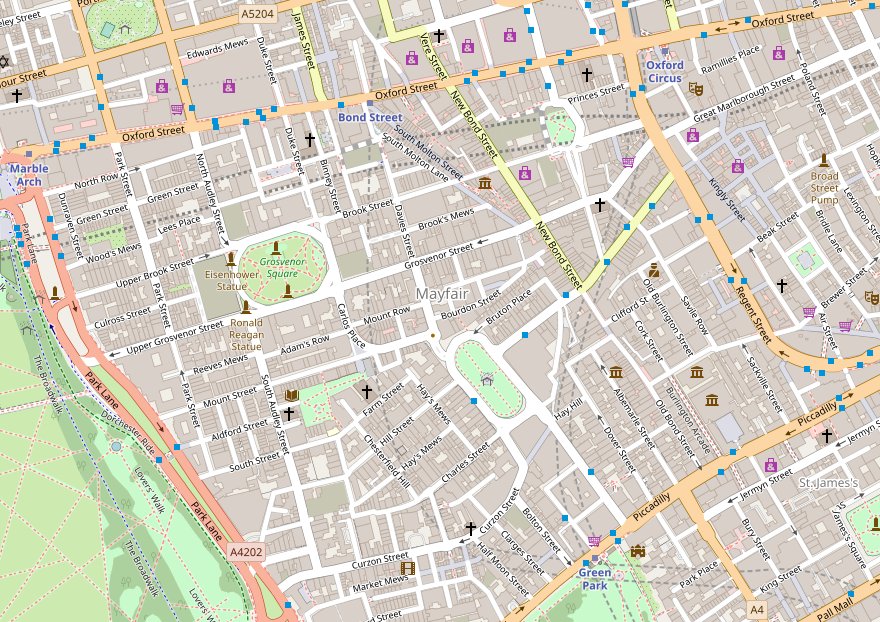

Gumbril next heads over to Saville Row, to see spiffy tailor Mr Bojanus, who is enthused by the ridiculous inflatable trouser inserts and want to mass produce them. Then, ‘From the world of tailors Gumbril passed into that of the artificial pearl merchants, …he began a leisured march along the perfumed pavements of Bond Street’. He visits the Grosvenor Gallery, Sotheby’s, then the Albemarle Gallery, where he confronts ‘a dismal collections of etchings’ by his friend Casimir Lypiatt. ‘Such a bad painter’, Gumbril muses, ‘going on like this year after year, pegging away at the same old things’.

Next up we meet Gumbril’s circle, all enjoying a boisterous meal at a restaurant based on the famed Eiffel Tower Café, a well-known Avant-Garde and Vorticist hangout, located at No 1 Percy Street, just off the Tottenham Court Road. These are an unpleasant, egotistical bunchof poseurs, hacks and bullies, including: Casimir Lypiatt, the terrible painter, a would-be Renaissance man, moralising aesthete, a blowhard ‘man of genius’ and dismal poet; Mr Mercaptan, a cynical critic and journalist, a ‘sleek, comfortable man young man’ with ‘ a rather gross, snouty look’; Coleman, the predatory, bearded, Cossack-like debauched ‘diabolist’, with ‘bright blue eyes and smiling equivocally and disquietingly as though his mind were full of some nameless and fantastic malice’; Shearwater, the icy, menacing, lugubrious ‘Physiologue’, or research biologist.

They are next drunkenly propelled out of the restaurant’s revolving door, into the ‘coolness and darkness of the street, a ‘real light opera summer night’, and without any ‘particular destination’, obviously. Again, an emptiness: ‘we are walking through the midst of seven million distinct and separate individuals all completely indifferent to our existence’, Coleman opines. Then, suddenly, ‘in the warm yellow light of the coffee-stall at Hyde Park Corner’, in a ‘cloak of flame and in bright, coppery hair’, appears one Myra Viveash.

Mrs Viveash is another shocking twenties’ character, the aristocratic socialite, the vamp or the flapper, a woman who is amoral, sexually voracious, inscrutable, callous, and, like London, haunted by ghosts of the war. She has a way of speaking, as if ‘from her deathbed’, as if ‘every word was her last’. Mrs Viveash is based on socialite Nancy Cunard, with whom Huxley had a very brief affair before being casually dumped, and this cruel portrait is clearly his revenge (Cunard actually went on to become a writer, publisher, and political activist, not at all the bored, vacuous and sexually voracious socialite presented here). ‘The Viveash’ is out and about with her new beau, cartoonishly loathsome toff, Bruin Opps, actually monocled and top-hatted: “I hate everyone poor, or ill, or old”, he remarks on seeing some destitute people at the Hyde Park cab rank, “Rot the people, blast the people, damn the Lower Classes”. The group all drunkenly go their separate ways home, to Tottenham Court Road, Mayfair, Pimlico, Maida Vale, Bloomsbury….

A later Mrs Viveash scene fascinatingly contrasts with Virginia Woolf’s treatment, two years later, of her iconic urban woman in town, the flaneuse, Mrs Dalloway. Mrs Dalloway, recall, relishes and engages with London, as she walks from Westminster to Bond Street: ‘Heaven only knows why one loves it so, how one sees it so…. creating it every moment afresh’; this is what ‘she loved; life; London; this moment of June’. Not so the predatory Myra Viveash.

These women engage with London very differently. Mrs Dalloway joyously emerges onto College Street, with ‘What a lark! What a plunge!’ Mrs Viveash, on the other hand, ‘descended the steps into King Street, and standing there on the pavement, looked dubiously to the right and left.’ A similarly sunny summer day, yet, for Myra Viveash ‘life seemed a little dim this morning’. Mrs Viveash isolated, bored and aimless, with endless free time, has a terrifying vision of emptiness; ‘steppes after steppes of ennui, horizon beyond horizon for ever the same’. Luckily for her, she bumps into Gumbril outside the London Library, and, having nothing better to do, corrals him, with ease, into spending the rest of the day (‘We must lunch at Verrey’s’), evening and night roaming the West End.

A little later, another remarkable sequence set in London’s streets foregrounds the novel’s obsession with the fake and the exploitative. Gumbril is out again roaming the streets, but this time, he sports a ludicrous fake beard, a manly so-called ‘beaver’, copied from Alpha-Male Coleman, which dramatically transforms him from arty wimp into the ‘The Complete Man’, a domineering, hearty, Rabelaisian, sexual predator. On Queensway, Bayswater, ‘sauntering past Whiteley’s with the air of someone who knows he has the right to a good place’, he spies his prey. This is Rosie Shearwater, bored, lonely, distractedly window-shopping, looking at ‘New Season Models’; at travelling trunks, fitted picnic baskets, corsets, hats, cigars and wine, at sports accessories, school uniforms, gentlemen’s hosiery. To the ‘Complete Man, she ‘seemed desirable and accessible prey’, ‘flexible and tubular, like a section of boa constrictor’. He ‘makes an inventory of her features’ and makes a move. Amazingly, he is successful. They go into Hyde Park, then back to hers at Bloxham Gardens, Maida Vale.

A decentred, delirious London is brilliantly captured in the novel’s final chapters. Gumbril has finally decided to leave for Paris (as did many of the pre-war Avant Garde, such as Pound, Lewis, H.D.) and he and Mrs Viveash motor round London late at night to bid one last farewell to the gang. They are driven pointlessly, in a taxi, for hours ‘back and forth, like a shuttle, from one end of London to the other’. Mrs Viveash insists that they must pass through Piccadilly Circus as often as possible, as she adores the illuminated lights; ‘Those wheels that whizz round til the sparks fly out, that lovely bottle of port filling the glass…too lovely’. For Mrs Viveash, this vortex is her London: ‘They’re me. Those things are me’. For Gumbril they are a revolting symbol of all that is most ‘bestial and idiotic in contemporary life… their flickers, their gibbers and twitches -what? Restlessness, distraction, refusal to think, anything for a quiet life’. Gumbril prefers the Circus’s Regency County Fire Office –its ‘dignity, beauty, repose.’

Unfortunately, everyone is either out, or ignoring them. Finally, desperately, on this ‘Last Ride’, they order the taxi south, an ‘immensely long way away’, over the river to ‘Golgotha Hospital, Southwark’ (Guy’s), to see Shearwater, the biologist. In a startling final image of twenties London, all this movement without progress, all this pointless energy and bluster, Shearwater, in a scientific experiment (and surely predicting the rise of Peloton©) is furiously pedalling on a fixed cycling machine, ‘pedalling unceasingly like a man in a nightmare’. Sweating furiously, pedalling all day, for days, but not moving, now delirious and hallucinating, ‘he was far away, he was escaping’. He would be ‘getting on for Swindon…nearly at Portsmouth…at Dover now, crossing the Channel’.

Viveash and Gumbril, are left looking out at the lights of London Bridge and Blackfriars Bridge. ‘Tomorrow will be as awful as today’, Mrs Viveash concludes.

Ged Pope reads and writes a lot about London. His latest book was All the Tiny Moments Blazing: A Reader’s Guide to Suburban London (2020). He is currently researching a book on Working-Class London fiction.

He teaches at ‘IES Study Abroad, London’, introducing the city and its culture to US students.

All rights to the text remain with the author.