Robert B. Todd

London is at the heart of Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room (1922). The novel’s fourteen chapters depict the life and death of Jacob Flanders, born around 1887. He is seen first as a child with his widowed mother on holiday in Cornwall and living modestly in Scarborough (chapters 1-2), then as a student at Cambridge (chapter 3) and on an excursion with a university friend and his family again in Cornwall (chapter 4). But after 1909 he is in London, twenty-two years old and ready to make his way in the capital.

Chapters 5-10 and 13-14 show him as a trainee lawyer and an unencumbered bachelor engaged in an active social life, including two casual flirtations with young women (chapters 5-10). He then enjoys an extended tour to France, Italy and mostly Greece, and starts an affair with an older woman (chapters 11-12). Finally, after a summer’s day in London in 1914 (chapter 13), he emerges as an early victim of the First World War, his mother and a friend left to clear his room – the room of the title (chapter 14).

Jacob’s biography is not a straightforward chronology, but is presented in short episodes in often abrupt succession, with a narrator’s voice intervening, and some arresting imagery (the underground is ‘hollow drains lined with yellow light’).

Imagine a series of film clips and having to draw connections and seek meaning. Yet within this context the relevant eight chapters display, amongst so much else, a vivid picture of London and Jacob’s relation to it.

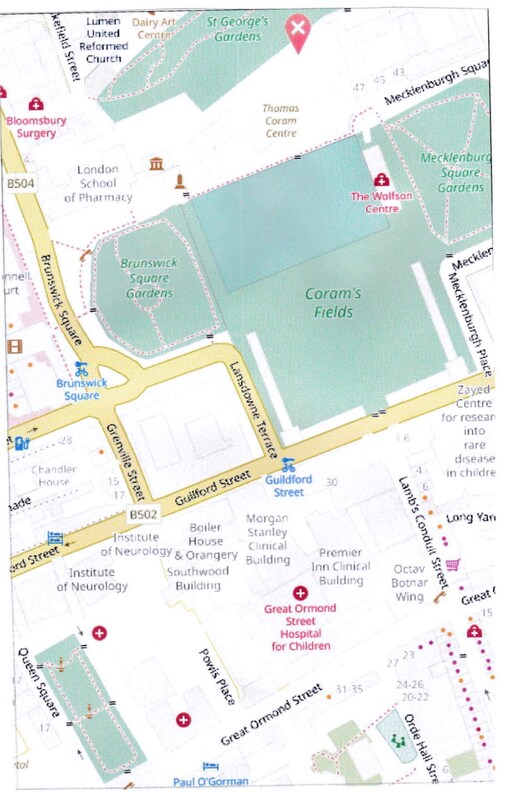

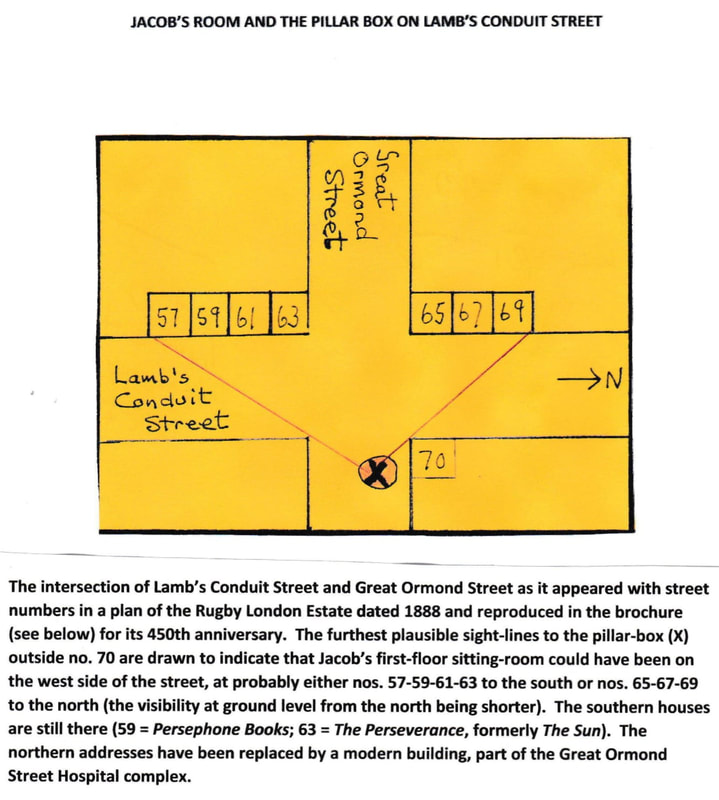

At its centre is Jacob’s lodging-house, at the eastern edge of Bloomsbury, in one of the four-storey houses at the northern end of Lamb’s Conduit Street, part of the Rugby Estate since the sixteenth century. He had two rooms on the first floor, the sitting-room overlooking the street.

Street directories from around 1910 identify most of the houses on this street as shops, located, as they still are, on ground floors in a street known for retail trade since the early nineteenth century. But in the years before the First World War there were no boutiques and eateries, only places catering to basic needs: bakers, grocers, a bicycle maker. The census for 1911 shows the upper floors of the houses occupied by proprietors and their families, or by lodgers of modest means, like Jacob, a poor boy, despite his elitist education.

From his sitting-room window Jacob could see a confectioner’s shop, and also a letter-box. Since the only post-office was no. 70 on the north-east corner of Lamb’s Conduit Street and Great Ormond Street, he has to be looking at the box that stands outside Ryman’s Stationery (it is a George V box, so there only after 1910). To have that view, Jacob has to be living on the west side of the street, not too far north or south of the intersection with Great Ormond Street. Persephone Books at no. 59, publisher of, among many other women, Virginia Woolf, would fit the bill.

Virginia Woolf had briefly lived nearby, when, scandalously in the eyes of some, she shared a house with four men, at no. 38 Brunswick Square, from late 1911 to mid-1912. The house is gone, marked by a plaque on the Institute of Pharmacy, on the north side of the square. She must often have headed out from it south to Guilford Street, and up Lamb’s Conduit Street, to shop or post one of her endless letters in that box at the corner of Great Ormond Street, and perhaps develop the fantasy found in the novel of the street’s glorious eighteenth-century past (‘Long ago great people lived here’).

Virginia Woolf had briefly lived nearby, when, scandalously in the eyes of some, she shared a house with four men, at no. 38 Brunswick Square, from late 1911 to mid-1912. The house is gone, marked by a plaque on the Institute of Pharmacy, on the north side of the square. She must often have headed out from it south to Guilford Street, and up Lamb’s Conduit Street, to shop or post one of her endless letters in that box at the corner of Great Ormond Street, and perhaps develop the fantasy found in the novel of the street’s glorious eighteenth-century past (‘Long ago great people lived here’).

She had a friend on Great Ormond Street, Saxon Sydney-Turner, an eccentric and erudite civil servant, who after 1904 lodged at nos. 37/39 (destroyed in the blitz in 1941 and rebuilt) in two furnished rooms. This was exactly Jacob’s living arrangement, which was perhaps modelled on Saxon’s. Great Ormond Street, like Lamb’s Conduit Street, was close to the grim poverty of Ormond Yard, the mews from which Jacob heard late at night the cries of a drunken woman (“Let me in! Let me in”).

Virginia’s time on Brunswick Square colours her account of one of Jacob’s girl-friends, Fanny Elmer. This artist’s model and aspiring painter walks through the ‘disused graveyard’ that Virginia could see from her second-floor window at the back of the Brunswick Square house. This is St George’s Gardens, a splendidly preserved former graveyard for two Bloomsbury churches, in Jacob’s time near the Foundling Hospital (freeholder of 38 Brunswick Square), the charity with a massive orphanage that once dominated what today is Coram’s Fields. The buildings are long gone, but their history is preserved in The Foundling Museum at the north-east corner of Brunswick Square.

Fanny at one point walks towards Guilford Street and is said to be ‘in the neighbourhood of the Foundling Hospital’ as she looks south down Lamb’s Conduit Street, hoping to catch sight of Jacob as he unlocks his front door, further proof that he lived at the northern end of the street. From where she stood she could hardly have spotted him much beyond Great Ormond Street,

Within his rooms Jacob’s life was sometimes cerebral (‘Plato’s argument is stowed away in Jacob’s mind’), sometimes carnal (‘They shut the bedroom door behind them’). Beyond them, he absorbed the city in all its complexity: its poverty when he visited St Paul’s Cathedral (‘an old blind woman … singing not for coppers, with her dog against her breast’); the squalor surrounding the wealthy audience when he went to Covent Garden on a gala night (‘the little thief … caught in the empty market-place’); the frantic teeming masses seen going back and forth across Waterloo Bridge (‘That old man has been crossing the Bridge these six hundred years’); the flower seller outside the mansion in Grosvenor Square when he dined with a titled lady (‘Moll Pratt … offering violets for sale’).

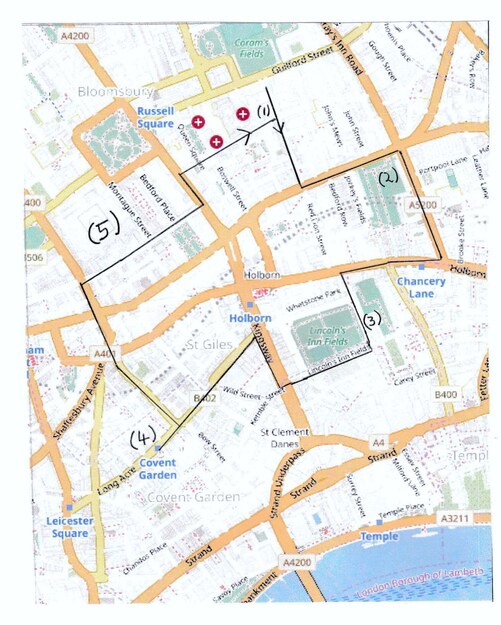

Our ‘Jacob’s Walk’ will show how he engaged with London.

First, we go south from his lodgings on Lamb’s Conduit Street to Theobald’s Road, as Jacob did every workday morning, then turn east towards Gray’s Inn, where he toiled in a legal office (‘Head bent down, a desk, a telephone’), probably articling to be a solicitor. Then we go down to Holborn, and on into Lincoln’s Inn Fields, entering the magnificent New Square of Lincoln’s Inn where Jacob’s wealthy friend from university Richard Bonamy lived. In his rooms these two Cambridge-trained minds clashed on abstruse subjects (‘“Objective something”, said Bonamy’) to the amusement of his ‘daily’ Mrs. Papworth of Endell Street, Covent Garden.

And that is where we go to next. He went to the opera house, invited by the mother of a Cambridge friend for a performance of Tristan und Isolde (‘This fellow Wagner’…), though he also frequented ‘the promenade at the Empire’ Leicester Square in the days when that theatre offered not films but dancers ‘whirling across the stage in white flounces’. Here he acquired Fanny as his new girl-friend after being abandoned by the duplicitous Florinda, the other half of the ‘they’ behind whom the bedroom door was shut.

Finally, we return to Bloomsbury and the British Museum (‘one solid immense mound, very pale, very sleek’), where Jacob, in between observing female scholars toiling, as Virginia Woolf herself often did, in that temple of learning, once studied Marlowe for an article on the law governing indecency in the theatre.

When we return to Lamb’s Conduit Street via Queen Square and Great Ormond Street we can seek refreshment. Today that is easily done, but in Jacob’s day there were only two ‘coffee rooms’ (at nos. 57 and 86) and two pubs (The Sun, now The Perseverance, at no. 63, and The Lamb, at no. 94). There are many more ‘coffee shops’, but the pubs are still there, as is the local undertaker, a survivor amidst death, A. France, at no. 45.

This walk is not, of course, in the novel, and perhaps cannot rival Clarissa Dalloway’s famous walk from Westminster to Bond Street with which Mrs. Dalloway opens. But it does capture much of Jacob’s experience of London. He walked a great deal, home on foot once from a Guy Fawkes Night party on Parliament Hill Fields, on another occasion from Hammersmith ‘in January between two and three in the morning’, and less strenuously from Soho on ‘a wet November night’ after dinner with Florinda.

His most important walk was his last one, taken in the summer of 1914. He had met Bonamy by the Serpentine in Hyde Park, and revealed his latest love, the married Sandra Wentworth Williams, whom he had encountered in Greece. As he returned to his lodgings via Piccadilly and came to Covent Garden, Clara, the sister of one of his Cambridge friends, recognized him as she was going to the opera, a wealthy and respectable young lady Jacob had neglected in order to play the field.

But he is not seen arriving back in Lamb’s Conduit Street, and never seen again in person in his room. He is only a memory when next we see his mother and Bonamy clearing the room of his effects after his death in the war. Invitations to social events for the last summer of peace lie strewn on the table as a poignant reminder of happier times. Like Rupert Brooke, Virginia Woolf’s childhood friend, whose background he shared (Rugby and Cambridge), Jacob must have volunteered right at the beginning of the war and died early in the conflict. The novel’s final words have his mother holding out ‘a pair of Jacob’s old shoes’, a relic of his endless walks around the city.

London, then, the site of Jacob’s somewhat misspent youth, could have been the site of his future – perhaps as a wealthy solicitor in a good marriage, with oats sown and Lamb’s Conduit Street a distant memory. His life may have been cut short in the fields of Flanders, a place of carnage that significantly bore Jacob’s surname. He had once visited Wellington’s tomb in St Paul’s to revere England’s leader in its last European war. He died a minor hero in the next one. That war was on the horizon that summer’s day in 1914, in the image of one of his Cambridge friends working in the Admiralty on Whitehall. Readers of the novel in 1922 would have recalled its First Lord Winston Churchill, architect of the Gallipoli expedition, on which Rupert Brooke died.

The London of Jacob’s Room was a young man’s world of hopes, dreams and pleasure, before responsibility is assumed. It was also a young woman’s world, Virginia Woolf’s, after she moved to Bloomsbury in 1904. Living in successive squares in the Bloomsbury area (Gordon, Fitzroy, and Brunswick Squares) and rubbing shoulders with Cambridge-educated talents (a John Maynard Keynes or a Clive Bell), and innovative artists (Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, her sister Vanessa), she slowly became a writer. A decade later in Jacob’s Room she offered her fictional version of that era, a homage to an earlier London of hope and pleasure, of culture and adventure, and to places she knew well in a city she loved, conveyed imaginatively through Jacob Flanders’s life – a life abruptly ended by war.

Jacob’s Room is not just a modernist experiment in the presentation of character and plot. It is a tribute to London, and an elegy for an era in its history that ended in 1914.

Robert B. Todd is a retired Professor of Classics (University of British Columbia, Vancouver). An undergraduate at University College, London, and a frequent visitor to, and occasional resident of, Bloomsbury, he is currently working on the district’s urban geography in relation to Virginia Woolf’s fiction and other writings. He has two articles in the current Virginia Woolf Bulletin 63 (2020).

Further Reading

Virginia Woolf: Jacob’s Room

Edited by Kate Flint. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 1992.

Edited by Sue Roe. Penguin Classics, 1992.

Edited by Vara Neverow. Orlando etc.: Harcourt, 2008.

Lisbeth Larsson. Walking Virginia Woolf’s London: An Investigation in Literary Geography. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. Ch. 4 (81-106): ‘A Brief Moment in Bloomsbury: Jacob’s Room’.

Woolf and London

Jean Moorcroft Wilson. Virginia Woolf, Life and London: A Biography of Place. London & New York: I.B. Tauris, 2000.

The District

David A. Hayes. East of Bloomsbury: Streets, Buildings and Former Residents in a Part of the London Borough of Camden. London: Camden History Society, 1998

The Rugby Estate

https://www.rugbyschool.co.uk/about/history/450th/450thanniversary-events

UCL Bloomsbury Project: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bloomsbury-project/streets/rugby.htm

The Foundling Museum and St. George’s Gardens

www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk

www.friendsofstgeorgesgardens.org.uk

All rights to the text, maps and photographs remain with the author.