Anne Witchard

A version of this article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers here.

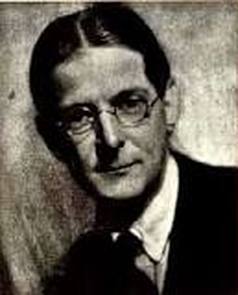

London was my city. It was in my bones and my blood, and part of my work, I knew, would be an attempt to re-present its life.’ – Thomas Burke, Son of London (1946)

In 1914, as war broke out, the London publishing firm, George Allen and Unwin, was offered a manuscript which it very much wanted to take on but which represented ‘too startling a departure’ from the character of its list. Looking back on his career in The Truth About a Publisher (1960), Stanley Unwin considers with regret ‘how frequently the most attractive proposals come one’s way at the moment when it is impracticable to accept them.’

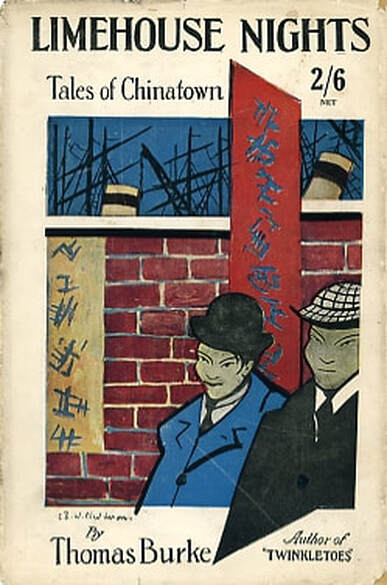

The manuscript in question was a collection of short stories by a relatively unknown writer, Thomas Burke, entitled Limehouse Nights: Tales of Chinatown. ‘It must be remembered,’ writes Unwin, ‘that the attitude towards books was much more squeamish and puritanical in 1914 than it has been since 1918. But we were so impressed by the book that we at once commissioned him to write Nights in Town, which we published with success.’

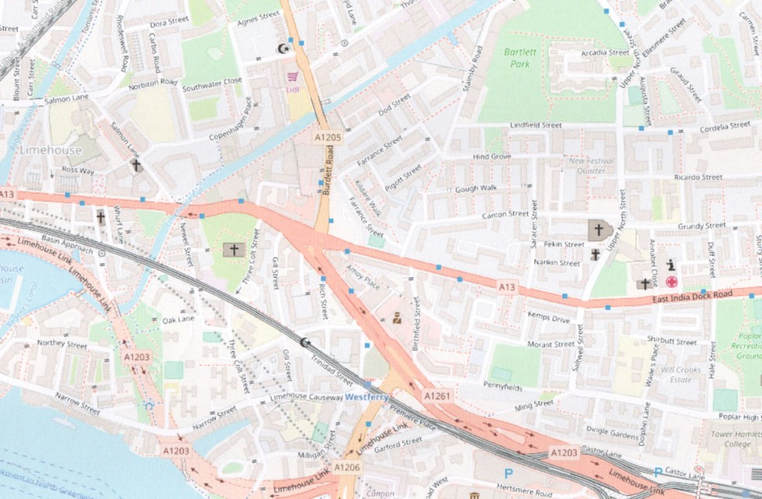

Nights in Town: A London Autobiography (1915) was conceived in the tradition of urban guide for the armchair tourist, a collection of personal vignettes of the capital’s districts by night. Burke is the seasoned habitué of dark side-streets that lead ‘to far countries or to secret encampments of alien and outlaw.’ In the chapter ‘A Chinese Night: Limehouse’ he conjures up the remote dockside byways of the East End as a place of adventure, contrasting the ‘corpse electrified’ of Piccadilly Circus where dreary bands play bilious waltzes in beer cellars, with the thrilling possibilities to be afforded by boarding an East-bound omnibus for Limehouse Causeway.

Nights In Town earned its author critical acclaim for its originality and lyrical prose style, meanwhile Burke continued to try and place his collection of ‘Chinese’ tales. When eventually Limehouse Nights was accepted by Grant Richards it had been refused by twelve publishing houses. All thought it too shocking. William Heinemann blamed the ‘constrained condition of mind’ indicated by the recent suppression of D. H. Lawrence’s novel, The Rainbow (1915), which had been prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act because of its likelihood to undermine the nation’s moral health in a time of war. ‘I think that was much to be regretted,’ Heinemann wrote to Burke, ‘but it is a good illustration of the tendencies just now, and an indication that the interest in the psychology of the pervert is not likely to appeal as long as the war lasts.’ Andrew Melrose pronounced unequivocally that he wanted ‘nothing to do with books about white girls and chinks.’ However, Grant Richards (whose authors included George Bernard Shaw, G. K. Chesterton and Arnold Bennett) made up his mind that ‘Thomas Burke and Limehouse Nights were just too good to let go,’ even though he did anticipate ‘trouble’ from the book. Richards took the precaution of soliciting letters of support and encouragement from eminent literary figures, among them Ford Madox Ford who dutifully read the book in France to the sound of ‘Bosche shells.’ As for ‘the immorality’ Ford commented, ‘I never thought about it, so that it cannot be so very immoral,’ unless, he joked, ‘the shell shock which has since sent me home was accentuated’ by the stories.

On publication, The Times reviewer took a more serious view of Limehouse Nights. Burke was condemned as a ‘blatant agitator’ for his evocative portrayal of a hybrid East End: ‘In place of the steady, equalised light which he should have thrown on that pestiferous spot off the West India Dock Road, he has been content … with flashes of limelight and fireworks.’ The book achieved instant notoriety by being banned by the circulating libraries, Boots and W. H. Smith. Arnold Bennett (who had just been appointed to the Ministry of Propaganda by press baron, Lord Beaverbrook) warned Burke that the possibility of securing a conviction was being seriously discussed at ‘headquarters’, and that he himself feared the worst. All this of course was excellent for sales and the book quickly went into further editions.

But what was it, exactly, that ‘occasioned the pother’? Some thirty years and another war later, John Gawsworth, found it difficult to imagine, ‘when James Joyce’s Ulysses is issued, and reissued in London,’ that ‘the accouchement of Limehouse Nights – surely some occasion in modern literary history? – was attended by acute anxiety both for the author and the publisher.’ In his preface to a posthumous edition of Burke’s Best Stories (1950) Gawsworth wonders was it ‘the sadistic motif underlying so many of his themes? No I do not think so: but would suggest, rather, that it was the novel, and to most unsavoury, implication that Yellow Man cohabited with White Girl in that East End of an Empire’s capital surrounding Limehouse Causeway.’

In 1916, the fact of relations between Chinese men and white women had become an issue of critical national concern. The opening story of Limehouse Nights, ‘The Chink and the Child’, about the devout love of a Chinese man for a white girl was attacked on the grounds that it ‘threw a sentimental glamour’ over the relations between white women and yellow men and ‘might have the harmful effect of encouraging the growth of a tendency that was likely to have disastrous consequences.’ In the face of war the very existence of foreign quarters threatened the idea of a nation wishing to believe itself socially and ethnically homogeneous. Most worryingly, the fact of co-habitation in Chinatown undermined the hierarchical structure of race that upheld Britain’s imperial status quo. Burke’s tales of Limehouse love troubled concepts of ‘purity’ and ‘pollution’ that had become insistent undercurrents of early-twentieth century thinking. Eugenicists, social scientists and psychologists maintained that Britain was in a state of physical and moral decline. Now the country was engaged in a war that was welcomed in conservative quarters for its ‘purifying fire’, Royal Academy sculptor W. R. Colton published an essay in The Architect magazine in 1916 expressing the hope that England might finally rid itself of degenerate foreign influence disseminated by the likes of Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, the futurists, cubists, and ‘the whole school of decadent novelists’.

In 1916, the fact of relations between Chinese men and white women had become an issue of critical national concern. The opening story of Limehouse Nights, ‘The Chink and the Child’, about the devout love of a Chinese man for a white girl was attacked on the grounds that it ‘threw a sentimental glamour’ over the relations between white women and yellow men and ‘might have the harmful effect of encouraging the growth of a tendency that was likely to have disastrous consequences.’ In the face of war the very existence of foreign quarters threatened the idea of a nation wishing to believe itself socially and ethnically homogeneous. Most worryingly, the fact of co-habitation in Chinatown undermined the hierarchical structure of race that upheld Britain’s imperial status quo. Burke’s tales of Limehouse love troubled concepts of ‘purity’ and ‘pollution’ that had become insistent undercurrents of early-twentieth century thinking. Eugenicists, social scientists and psychologists maintained that Britain was in a state of physical and moral decline. Now the country was engaged in a war that was welcomed in conservative quarters for its ‘purifying fire’, Royal Academy sculptor W. R. Colton published an essay in The Architect magazine in 1916 expressing the hope that England might finally rid itself of degenerate foreign influence disseminated by the likes of Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, the futurists, cubists, and ‘the whole school of decadent novelists’.

The association of Chinese immigrant populations with vice, narcotics, prostitution and gambling (a fear imported from America) prompted increased restrictions of the Aliens Act under the Defence of the Realm Act of 1914 (DORA). Newspapers targeted foreigners living in Britain as ‘the enemy within’ and foreignness was linked to treason, espionage and subversion. The individual’s moral health was considered interdependent with racial fitness and national well-being, crucial both to Britain’s defence capabilities and her status as a world power. In 1916, stories about white women and Chinese men in Limehouse vividly symbolised the degeneration of British society.

The ‘problem’ of interracial alliances among the Chinese in Limehouse was accounted for, not as it conceivably might have been by the almost total absence of Chinese women, but by the giddy susceptibility of a certain ‘type’ of white woman to ‘Oriental’ vice. In 1915, a series of addresses by the Bishop of London was published in a collection entitled Cleansing London, a patriotic call that linked the home front with the front line. Concern with the moral battles that must be won if the war was to be a true victory was focused on the behaviour of women. It was the task of all ‘the women of London,’ commanded Bishop Ingram, to ‘purge the heart of the Empire before the boys come back.’ The usual newspaper reports of gambling raids, opium smoking, and hatchet fights in Chinatown, now combined with accounts of English girls being ‘inveigled in the meshes of Chinese sorceries’ for example, or ‘made to serve as votaries at the altars of their gambling hells’, stories which would escalate wildly with the onset of war.

It was at the end of the 1890s that the reading public first became aware of Limehouse as London’s Chinatown. Operations between England and the Far East had been established since the 1860s by British merchant steamship companies. These employed hundreds of men signed on in China’s treaty ports. Whilst soldiers and entrepreneurs set sail from Limehouse Reach to defend and extend Britain’s interests in China and the Far East, the capital’s East End became cosmopolitan with an influx of Indians, Malaysians, and Chinese. Along the dockside streets, Limehouse Causeway and Pennyfields there developed a tiny Chinatown. Settled Chinese opened grocery stores, association halls, restaurants, laundries and lodging rooms that catered for seamen, culturally isolated by language and the transience of their stay. At its peak, in 1921, the census returns for the Chinese population of Limehouse was only 337, and while this was an increase on 101, in 1911, and while the Limehouse Chinese accounted for half of London’s total ‘alien-Chinese’ presence, the figures were negligible. The Chinese were a scapegoat for what were considered major social ills, yet the force of this negativity bore no relation at all to the size of their presence. The myth of Chinese Limehouse was always far greater than its actuality.

It was at the end of the 1890s that the reading public first became aware of Limehouse as London’s Chinatown. Operations between England and the Far East had been established since the 1860s by British merchant steamship companies. These employed hundreds of men signed on in China’s treaty ports. Whilst soldiers and entrepreneurs set sail from Limehouse Reach to defend and extend Britain’s interests in China and the Far East, the capital’s East End became cosmopolitan with an influx of Indians, Malaysians, and Chinese. Along the dockside streets, Limehouse Causeway and Pennyfields there developed a tiny Chinatown. Settled Chinese opened grocery stores, association halls, restaurants, laundries and lodging rooms that catered for seamen, culturally isolated by language and the transience of their stay. At its peak, in 1921, the census returns for the Chinese population of Limehouse was only 337, and while this was an increase on 101, in 1911, and while the Limehouse Chinese accounted for half of London’s total ‘alien-Chinese’ presence, the figures were negligible. The Chinese were a scapegoat for what were considered major social ills, yet the force of this negativity bore no relation at all to the size of their presence. The myth of Chinese Limehouse was always far greater than its actuality.

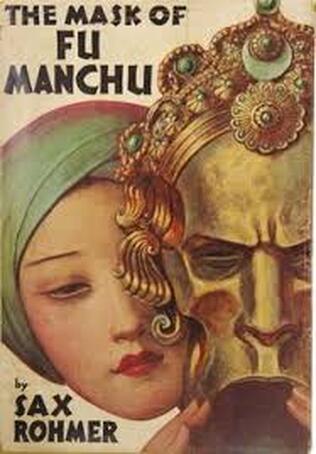

In Sax Rohmer’s best-selling stories of Dr Fu Manchu, Limehouse is a place of shuttered hovels, mysterious passages, ‘dark narrow streets and sinister-looking alleys,’ home to Rohmer’s arch-criminal mastermind, ‘the yellow peril incarnate in one man.’ The first three Fu Manchu books, published between 1914 and 1917, were a straightforward exploitation of current anxieties which makes the Chinatown fiction of his contemporary, Thomas Burke, appear all the more remarkable. While Rohmer’s tales of Fu Manchu reinforced contemporary fears with his evil ‘Chinamen’ whose interest in white women is part of their fiendish yellow plot to destroy the West, Burke’s collection of stories invests London’s Chinese Quarter with romance, however spurious. Burke’s Limehouse is as alluring as it is forbidding: ‘The glamorous January evening of Chinatown – yellow men, with much to spend – beribboned, white girls, gay, flaunting and fond of curious kisses – rainbow lanterns, now lit, and swaying lithely on their strings. In this depiction of Chinese New Year in Limehouse Causeway, readers are invited to suspend their moral judgement and forgive ‘the girls if they love on such a night and with such people.’ Limehouse Nights contrasts a played out West End with a robust East End bohemia, where the ‘people are sick perhaps with toil; but below that sickness there is a lust for enjoyment that lights up every little moment of their evening.’ West End theatres might be dazzling audiences with displays of orientalist exoticism but ‘saturnalias’ and ‘true Bacchanales’ were being performed in the East End streets.

In Sax Rohmer’s best-selling stories of Dr Fu Manchu, Limehouse is a place of shuttered hovels, mysterious passages, ‘dark narrow streets and sinister-looking alleys,’ home to Rohmer’s arch-criminal mastermind, ‘the yellow peril incarnate in one man.’ The first three Fu Manchu books, published between 1914 and 1917, were a straightforward exploitation of current anxieties which makes the Chinatown fiction of his contemporary, Thomas Burke, appear all the more remarkable. While Rohmer’s tales of Fu Manchu reinforced contemporary fears with his evil ‘Chinamen’ whose interest in white women is part of their fiendish yellow plot to destroy the West, Burke’s collection of stories invests London’s Chinese Quarter with romance, however spurious. Burke’s Limehouse is as alluring as it is forbidding: ‘The glamorous January evening of Chinatown – yellow men, with much to spend – beribboned, white girls, gay, flaunting and fond of curious kisses – rainbow lanterns, now lit, and swaying lithely on their strings. In this depiction of Chinese New Year in Limehouse Causeway, readers are invited to suspend their moral judgement and forgive ‘the girls if they love on such a night and with such people.’ Limehouse Nights contrasts a played out West End with a robust East End bohemia, where the ‘people are sick perhaps with toil; but below that sickness there is a lust for enjoyment that lights up every little moment of their evening.’ West End theatres might be dazzling audiences with displays of orientalist exoticism but ‘saturnalias’ and ‘true Bacchanales’ were being performed in the East End streets.

While Limehouse Nights capitalised on contemporary concern about miscegenation, Burke did not temper the romances he spun between white girls and their ‘yellow’ neighbours with the high moral tone and distaste that was taken by the establishment press with regard to such transgressions. Reviewers registered these lurid tales of Limehouse love on a sliding scale of shock value, ‘some too terrible for thought, some cheaply startling,’ yet what startles today is their erotic focus on the underage girl that went quite unremarked. As the ‘Chink’ rescues the ‘Child’ from the perils of the opium den whence she has fled her brutal father, the ‘midnight chimes of the clock above Millwall docks echo the number of little Lucy’s years’: ‘Twelve. … Twelve.’ Cheng Huan ‘had claimed her’ we are told, ‘but had not asked himself whether she was of an age for love … It may be that he forgot that he was in London and not Tuan-tsen.’ The moral standards of Chinese Limehouse are those of the genial rogue, restaurant-keeper, Tai Ling, first portrayed in ‘A Chinese Night’. He is not immoral, ‘for to be immoral you must first subscribe to some conventional morality.’

Burke’s Chinatown stories were constructed around an Orient of the mind, a twilight world of exotic ports and red-light districts. Sexual possibilities inhere in the very idea of a Chinese quarter, a Pekin Street or Amoy Place, insinuating that anything might be possible. Limehouse Nights partakes of the late-nineteenth century system of highly fantasised imagery that conflated the dark and barbaric East End with the mysterious Orient. The white girls of the stories are the lost or betrayed girl-children of late-Victorian cultural desire, reinvented as objects of Oriental lust. The feverish fascination of the late-Victorian aesthete with child whores and stage waifs reached its height of artistic devotion amongst Ernest Dowson and other Decadents in the 1890s. Limehouse Nights demonstrates the continuing cultural strength of the erotic child, but marks a shift from obsession with the child as icon of ‘purity’ to the new century’s fixation on the juvenile delinquent: ‘You might have seen her about the streets at all hours of day and night’.

Burke is always most insistent regarding age. Often it is twelve, occasionally fifteen, but mostly it is the ‘magic age of fourteen years’ that preoccupies. There is poor little Lucy Burrows and the tragic poet Cheng Huan; pretty prostitute Marigold Vassiloff and good-natured Tai Ling who live happily ever after; treacherous Gracie Goodnight who murders her nasty boss Kang Foo Ah and gets away with it; the sordid psychodrama of Daffodil Flanagan and her lover, Fung Tsin; Jewell Angel, the aerialiste (as trapeze artists were rather grandly known), fatally sabotaged for snubbing ‘half-caste’, Cheng Brander; and Beryl Hermione Chudder and her pimp, Wing Foo, in a story inspired by the siege of Sidney Street in 1911. There is the Cantonese-speaking copper’s nark, Poppy Sturdish and duped Sway Lim who gets his revenge. There is the evil Tai Fu and Pansy Greers who gets her revenge. Their social hub is the Blue Lantern pub. Here, ‘in an underground chamber near the furtive Causeway’ gather all ‘the golden boys and naughty girls of the district’ and here the little dancer, Gina of the Chinatown, sometime Casino Juvenile or Quayside Kid, is generally to be found standing on a table ‘slightly drunk, and with clothing disarranged, singing that most thrilling and provocative of rag-times: “You’re here and I’m here / So what do we care?”’

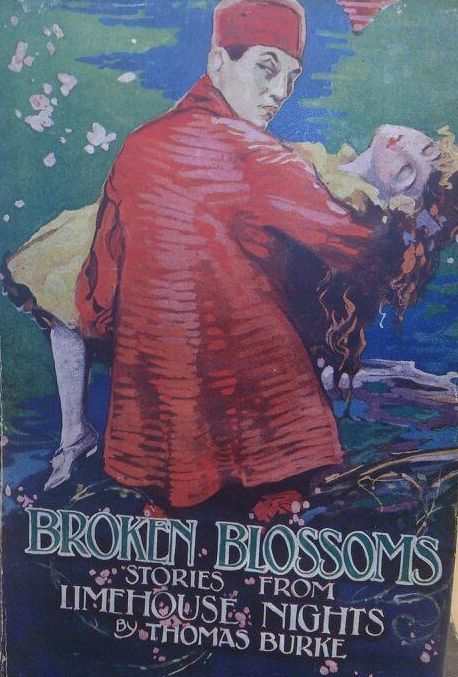

Grant Richards managed to secure New York publication ‘overnight’ with Robert M. McBride, whilst in the meantime, he recalls, Burke fretted about the possibility of prosecution at home: ‘Being of a more temperamental and more nervous nature he would not rest until I had agreed –for a consideration, I had better frankly confess – to cancel the clause in our contract which would have made him financially responsible for the costs of defending any action brought against me as the book’s publisher and for the payment of any losses or financial penalties incurred.’ The absence of moral censure regarding what H. G. Wells characteristically referred to as ‘rather horrible … “sexual circulation”’, contributed towards the book’s enormous impact in the States where ‘you were utterly behind the times if you were not intimately acquainted with Burke’s stories of Limehouse’. American interest was whipped up by racy reviews: ‘Amid erotomaniacs, satyrs and sadists – and if the full meaning of these terms escapes you, be thankful – he seizes scraps of splendid courage, beauty and pathos … do not miss Limehouse Nights’ urged the Boston Transcript. At the prompting of Mary Pickford, D. W. Griffith paid the massive sum of one thousand pounds for the film rights. The fog-bound dockside streets of Burke’s stories, the frowsy opium dens and illegal gambling parlours, haunts of his displaced Chinamen and ringletted Cockney waifs, are vividly realised in Griffith’s silent adaptation, Broken Blossoms (1919) which set a celluloid precedent for the imagery of Limehouse.

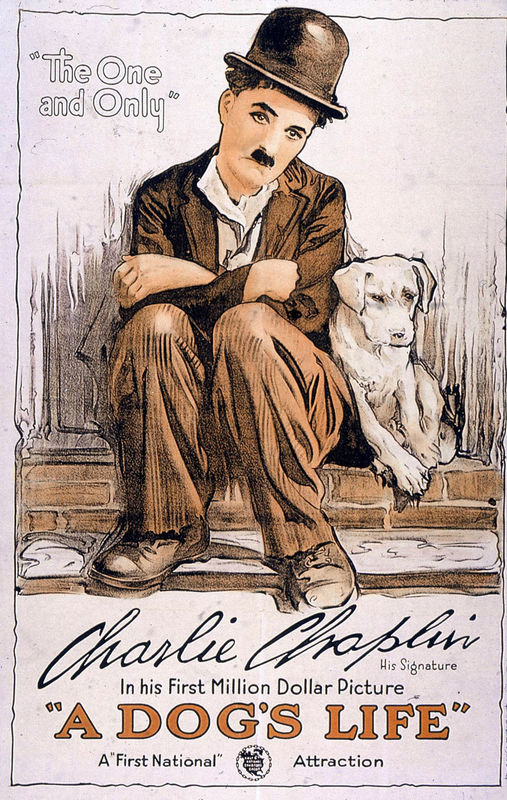

Other directors were keen to film Burke’s world. A homesick Charlie Chaplin credited Limehouse Nights as the inspiration for A Dog’s Life (1918) in which his character befriends a young dance-hall prostitute: ‘I got a feeling from reading Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights. … There is beauty in the slums! – for those who can see it despite the dirt and sordidness. There are people reacting toward one another there–there is LIFE, and that’s the whole thing!’ and Chaplin should have known as he was a London slum kid himself. In 1924, British director, Maurice Elvey (who had made London’s Yellow Peril, 1915) exploited Burke’s Limehouse scenario by combining a number of his plots in Curlytop (1924). Charles Brabin directed Twinkletoes in 1926, for which Colleen Moore, the ‘screen’s first flapper’ disguised her iconic bob under blonde ringlets to play the heroine: ‘Miss Moore shatters precedent and more than makes good as the little slum child of London’s Limehouse district,’ commented Variety.

While public reaction to Limehouse Nights was dramatic and divided, no prosecution was brought. By the 1920s it was no exaggeration to state that audiences knew every dark and dangerous alley of Limehouse as well as they knew the way to their corner grocery. To the annoyance of Limehouse residents, charabanc trips were put on by Thomas Cook for readers eager to search out the originals of Cheng Huan, Tai Ling and Marigold, and to stare at those real-life ‘children with sallow faces and un-English eyebrows’, whose existence, commented Rev. Birch, the rector of Limehouse, ‘one would regret were it not that they are often none the less delightful enough little creatures. At the same time Birch warned: ‘that those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.’

While public reaction to Limehouse Nights was dramatic and divided, no prosecution was brought. By the 1920s it was no exaggeration to state that audiences knew every dark and dangerous alley of Limehouse as well as they knew the way to their corner grocery. To the annoyance of Limehouse residents, charabanc trips were put on by Thomas Cook for readers eager to search out the originals of Cheng Huan, Tai Ling and Marigold, and to stare at those real-life ‘children with sallow faces and un-English eyebrows’, whose existence, commented Rev. Birch, the rector of Limehouse, ‘one would regret were it not that they are often none the less delightful enough little creatures. At the same time Birch warned: ‘that those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.’

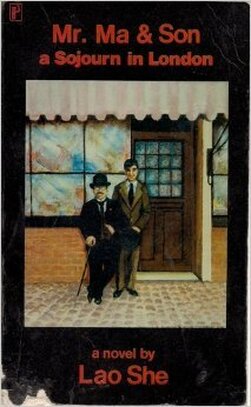

Throughout the 1920s novels, plays and films were notable for their offensive stereotypes of Chinese people. If we want a first hand account of what life was really like for the shopkeepers, transient seamen and restaurateurs that made up the major part of London’s Chinese community in London during these years, we only need turn to Chinese writer Lao She’s marvellous novel, Er Ma (Mr Ma and Son, 1929).

Lao She came to London in 1924 to take up a post teaching Chinese at the School of Oriental Studies (now the School of Oriental and African Studies) then at Finsbury Circus. The novel, drawing on his own experiences of life in London, takes issue with the popular cultural sinophobia of the Limehouse genre and its pernicious effect on the attitudes of Londoners to the Chinese amongst them.

Lao She came to London in 1924 to take up a post teaching Chinese at the School of Oriental Studies (now the School of Oriental and African Studies) then at Finsbury Circus. The novel, drawing on his own experiences of life in London, takes issue with the popular cultural sinophobia of the Limehouse genre and its pernicious effect on the attitudes of Londoners to the Chinese amongst them.

Thomas Burke’s star rose and fell along with the cultural resonance of Limehouse. Throughout his life and despite subsequent successes in diverse genres, his books would carry the hook ‘by the author of Limehouse Nights’. The ‘wretched book’ he would complain, has been ‘strung around my neck as a literary badge.’ During his later years, Burke expounded a belief in writing as an occult process, particularly in defence of the ‘ridicule to which I have been subjected for giving a falsely melodramatic picture of Limehouse life.’

It was certainly true that the notoriety of Chinatown exploded after the publication of Limehouse Nights. Burke needed to explain his part in this as magical rather than malign. Writing about ‘The Chink and the Child,’ Burke now owned that the location of the story and its Chinese element was quite arbitrary. It ‘had no origin as far as I know in China or Limehouse,’ it was only when casting about for a setting that the ‘West India Dock Road and the two Chinese streets … rose in my mind as exactly fitting.’ Here in the Chinese streets was ‘a whiff of something odd,’ here, he decided, ‘was a territory for a certain kind of story.’ Disingenuous perhaps, but for the complex and contradictory ways in which he upset social orthodoxies, Burke’s Limehouse Nights makes compelling reading.

London’s First Chinatown Today

When Burke wrote Limehouse Nights, Pennyfields was almost entirely inhabited by Chinese. Chong Ching, Chong Sam, Wong Ho, Yow Yip, Choi Sau, Ah Chong Koon, Pong Peng, and Cheng Pong Lai, are a few names taken at random from a collection of application forms for ration books during the First World War. By 1934, the Register of Electors shows that of twenty-seven houses listed in the street only one was inhabited by a Chinese family. The combined pressures of the Alien Restriction Acts of 1914 and 1919, together with police harassment were responsible for the decline.

Limehouse Causeway was widened in 1934 and a maze of alleys, courts and side streets, including several occupied by Chinese shops and lodging houses, were demolished to make way for blocks of flats. Slum clearance, together with the effects of the Depression and a slump in international trade, further diminished the Chinese population. Thomas Cook’s suggested route for an ‘East End Drive’ no longer made an ‘attraction’ of Limehouse.

The myth declined along with the reality and newspaper stories about the ‘dwindling population’ of Chinese Limehouse sympathised with ‘the sensational writer bereft of one of his more thrilling scenarios.’ Census figures from the 1930s indicate an acceleration of movement of Chinese to the West End and the outer suburbs. The Blitz helped finish the work begun by the LCC clearances.

In 1955, even more projected demolition prompted a letter to the editor of The Times from the avant-garde Situationist group:

We protest against such moral ideas in town-planning, ideas which must obviously make England more boring that it has in recent years already become. … The disappearance of pretty girls, of good family especially, will become rarer and rarer after the razing of Limehouse. Do you honestly believe that a gentleman can amuse himself in Soho? … Anyway, it is inconvenient that this Chinese quarter of London should be destroyed before we have the opportunity to visit and carry out certain psycho-geographical experiments we are at present undertaking.

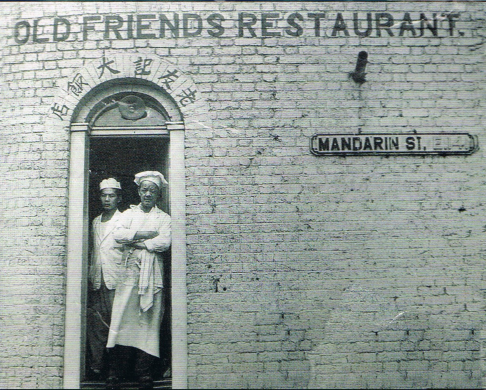

London’s Chinatown as we know it today began to take shape at this point. Encouraged by seedy Soho’s cheap rents and already established reputation for cosmopolitan dining, a few Chinese restaurants set up in the streets to the north of Leicester Square. Demand from West End theatre and clubbing crowds ensured their popularity, attracting more Chinese not just from the East End but from Hong Kong and the New Territories. Thanks to Docklands regeneration, London’s first Chinatown is now all but erased from the physical site of Limehouse Causeway and Pennyfields, The ‘Old Friends’ restaurant on Commercial Road offers a distant echo of the old Chinatown. It’s one of the oldest Chinese restaurants in London, though dating back only to the 1950s, so well after the dissolution of Limehouse’s Chinese community.

Only the evocative street names – Canton, Pekin, Amoy, Ming, Mandarin, Nankin – and a metal dragon sculpture coiled above the Limehouse exit of the Docklands Light Railway, remind us that once this district vibrated to a distinctly Chinese rhythm.

Anne Witchard is Reader in the department of English and Linguistics at the University of Westminster. Her publications include England’s Yellow Peril: Sinophobia and the Great War (Penguin, 2015), Lao She in London (Hong Kong University Press, 212) and Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie: Limehouse Nights and the queer speel of Chinatown (Ashgate, 2010). She has also contributed to the London Fictions website on Lao She’s Mr Ma and Son.

Further Reading

Thomas Burke, Nights in Town: a London Autobiography, London 1915

Limehouse Nights:Tales of Chinatown, London, 1916

Out and About London, London, 1919

Whispering Windows: Tales of the Waterside, London, 1921 (published in US as More Limehouse Nights, 1921)

The Wind and the Rain: a Book of Confessions, 1924

East of Mansion House, London, 1928

The Pleasantries of Old Quong, London, 1931 (also published as A Tea-shop in Limehouse, Boston, 1931)

City of Encounters: a London Divertissement, London, 1932.

Night-Pieces: Eighteen Tales, London, 1935.

Son of London, London, 1946.

Best Stories. London 1950.

Ng Kwee Choo, The Chinese in London, Oxford University Press, 1968

Marek Kohn, Dope Girls: the Birth of the British Drug Underground (2nd edition), Granta, 2003

John Seed, ‘Limehouse Blues: Looking for Chinatown in the London Docks, 1900-1940’, History Workshop Journal , 62, Autumn 2006

http://limehousechinatown.org/

All rights to the text remain with the author.