Peter Jones

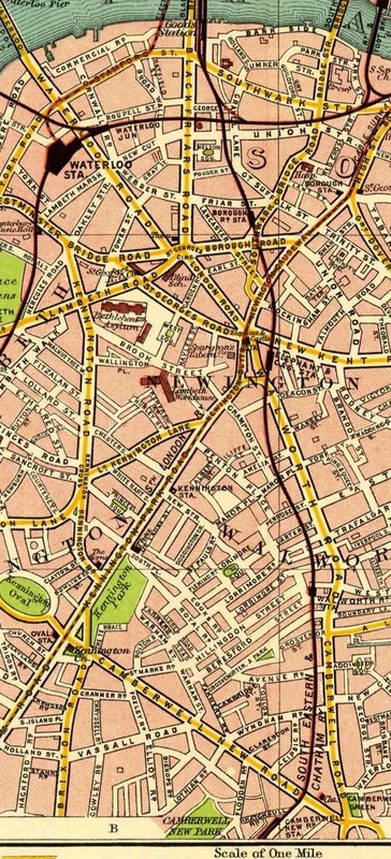

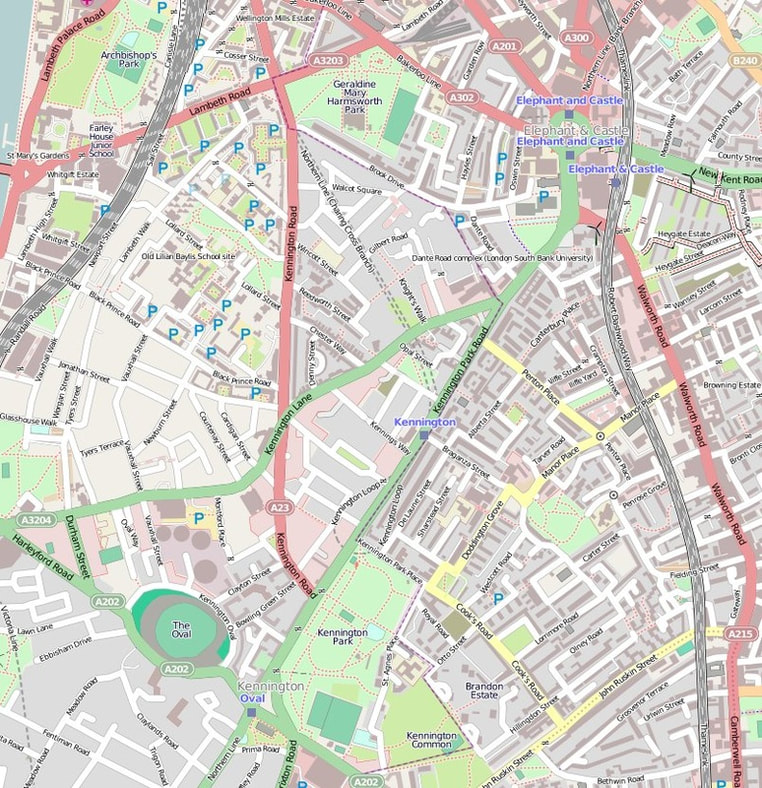

Somewhere beyond William’s, which supports the Obelisk, lies Kennington, famous for “Jim’s” and the “Original Pieman”; and beyond these again is Brixton; and between these two you shall find Arthur’s. This is an ambiguous direction; but then we night-seekers are jealous of our ill-fame, and the fear of the Oxford Movement is strong upon us. […] So I will leave the reader to identify Arthur’s for himself; and if he do not succeed, why, there are twenty other coffee-stalls between the Obelisk and Brixton, and the philosophers in charge of any one of them will answer to the name of Arthur. For time and the night-cars wait for the pleasure of no man, and “Arthur” (or “Guv’nor”) is a generic by-name for mine host of the kerbstone throughout London.

Albert Neil Lyons’ Arthur’s: The Romance of a Coffee Stall opens with this series of directions that are initially relatively coherent and easy to follow. The reader is encouraged to shadow the ‘night-seekers’ who travel south from the city in buses and trams. Passing the Obelisk that is still located at St. George’s Circus (having returned from a ninety year stay in Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park near the Imperial War Museum), we proceed down the London Road, through Elephant and Castle and then turn right onto Newington Butts. However, after this point our objective becomes much ‘ambiguous’ and difficult to trace. ‘Arthur’, we are informed, is merely a ‘by-name’ that refuses to point toward a specific person or location, but the most likely stopping point that lies ‘between the obelisk and Brixton’ is the Kennington/ Oval junction. Lyons is clearly a regular visitor to ‘Arthur’s’, and he has gained the confidence of the ‘ancient and admitted Freemen’ who gather at this coffee-stall including Arthur the owner, ‘Kitty the Rake’, ‘Robert Walpole’, and the ‘Dartigan Donkey.’ But before getting better acquainted with this compelling cast of characters, it would be useful to learn a little more about Lyons himself and then to give a brief introduction to the history of this culturally effervescent setting.

Lyons’ literary output is eclectic and resists easy classification. However, F.H. Pritchard in the introduction to Lyon’s Selected Tales (1929) summarizes it well when he alludes to the ‘keen wit of the gutter, the easy tolerance of the coffee-stall, and the rich comedy of the countryside’ that find expression in his novels. Much of what is known about Lyons’ life has been collected in a short article in which Alan Richardson advocates for a critical reappraisal of an unduly neglected ‘writer of considerable talent.’

Lyons (1880-1940) was born in the South African town of Kimberley and was educated at Bedford Grammar School in nearby Hanover. He received accountancy and legal training but his interests quite rapidly shifted to journalism. He began writing articles on military topics and when he was nineteen succeeded in gaining a low level post at The Critic. Soon after this he emigrated to London and the 1901 census lists him as living at the Hampden Club, Hampden Street (now Polygon Road) near Kings Cross Station, which provided lodgings for young writers and journalists. While in London, Lyons frequently contributed to the weekly newspaper The Clarion and in 1910 he would write a biography of the socialist campaigner Robert Blatchford, who edited this publication. The aspiring author married Dorothy Worrall when he was 29, and was living with her in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire by 1911. He would later move to Wivelsfield, and write books that touched on the life of the Sussex working classes such as Moby Lane and There Abouts (1916).

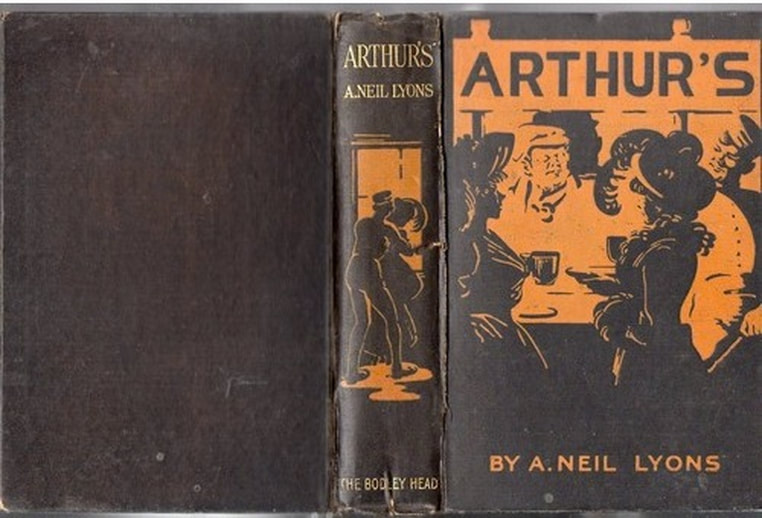

Lyons’ third book, Arthur’s (first published in 1908 by John Lane) was very well received by ‘the critics’ as well as the ‘reading public’, and it would ultimately pass through a total of four editions. This volume is made up of several short vignettes and it is split into two sections, the first portion of which was written in 1901 and the second in 1904. However, it is somewhat regrettable that this ebullient and cleverly plotted book has been allowed to slip into a state of almost total obsolescence. Lyons has received hardly any recent critical attention beyond a handful of peripheral references in literary histories. On the other hand, it is gratifying to see that Pickering and Chatto are due to publish a number of Lyons’ short stories in the third volume of British Socialist Fiction, 1884–1914, which is due out in September 2013.

Lyons’ third book, Arthur’s (first published in 1908 by John Lane) was very well received by ‘the critics’ as well as the ‘reading public’, and it would ultimately pass through a total of four editions. This volume is made up of several short vignettes and it is split into two sections, the first portion of which was written in 1901 and the second in 1904. However, it is somewhat regrettable that this ebullient and cleverly plotted book has been allowed to slip into a state of almost total obsolescence. Lyons has received hardly any recent critical attention beyond a handful of peripheral references in literary histories. On the other hand, it is gratifying to see that Pickering and Chatto are due to publish a number of Lyons’ short stories in the third volume of British Socialist Fiction, 1884–1914, which is due out in September 2013.

It is true that the eccentricity of Arthur’s can make it appear unapproachable or inaccessible to the modern reader, but this article makes the case that it is this work’s marginality that makes it so intriguing. This collection of interlinked short stories presents a counterpoint to accounts that fanned the flames of an emerging moral panic that focused upon the ‘Night Side’ of south London’s streets during the 1900s. The author taps into the rich vein of story-making that is characteristic of the cultural dynamics of the heterogeneous ‘coffee-stall company’, amongst which ‘you may sup your fill of ripe humanity.’ He is able to evince the distinctly accommodating qualities of this obscure nocturnal setting, which more conventional, sociologically orientated accounts, tended to disregard.

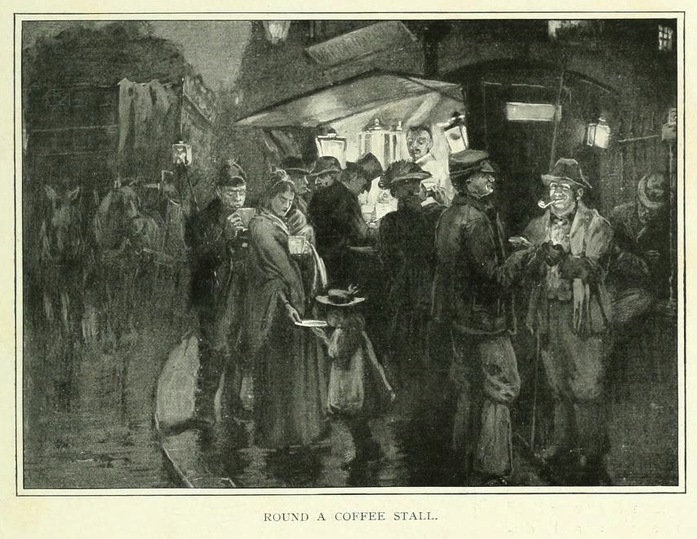

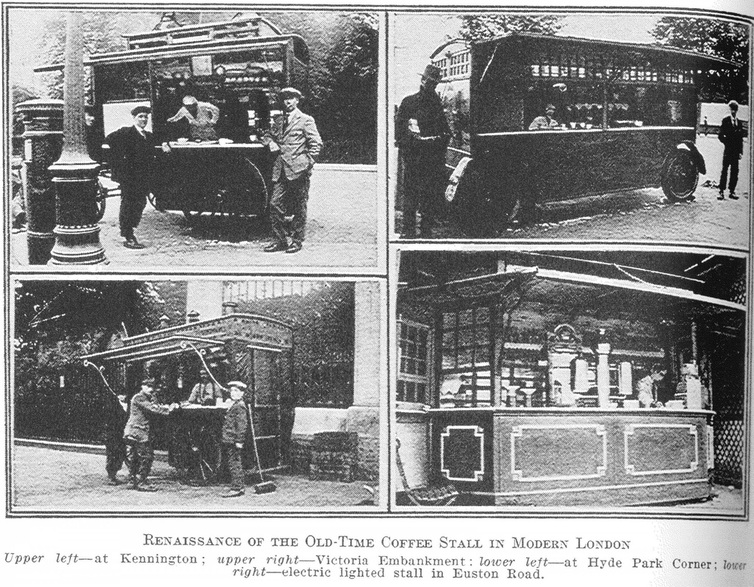

In the 1840s Henry Mayhew estimated that there were ‘upward of 300’ coffee stalls in the London area. However, twenty years earlier the ‘vending of tea and coffee, in the streets’ was virtually unheard of and ‘saloop’ was then ‘the beverage supplied from stalls to the late and early wayfarers.’ Stall-keepers occupied their pitches by the late evening in an effort to attract the ‘night-walkers’, ‘fast gentlemen’ and ‘loose girls’ who were out on the streets at night. They generally stayed open throughout the early hours to provide refreshments to labourers, navvies and market porters on their way to work in the morning. In The Cockney: a Survey of London Life and Language(1953) Julian Franklyn suggests that coffee stalls had their heyday during the fin de siècle and early twentieth-century—‘the great days of bohemianism and culture.’

On the corner of Shoreditch High Street and Calvert Avenue it is still possible to visit ‘Syd’s’, London’s one remaining ‘original’ coffee stall, which was founded in 1919 by Sydney Tothill.

In a video created in 2011 for the ‘Social Archive’ Project led by artist Shiraz Bayjoo, Syd’s granddaughter Jane Tothill (who now runs the stall) states that due to the rapid changes taking place in Shoreditch the future of her establishment looks somewhat ‘precarious.’

Syd’s is now a permanent installation, although such wheeled ‘vehicular cook-shops’ would originally have been drawn to their locations by horse or by manpower, and then secured with blocks. Indeed, mischievous revellers were said to have removed these stops from kiosks on Villiers Street, with the result that the stalls at the Strand end were set in ‘violent motion’ and hurtled down the hill towards the Thames. Having been secured, a hinged panel on the side of the kiosk would be lifted up and this would form a rudimentary roof or windbreak, which could accommodate customers ‘even in inclement weather.’ Coffee could be bought for a penny or a ha’penny from shining urns along with a range of edible items including cakes, muffins, sardines, pickled eggs and cabbage. Richard Rowe found that the presence of the stalls on the city’s streets to be a blessing because they resembled ‘little bit of Home come out of doors to comfort the cheerless and the cold.’ During the 1880s coffee was even promoted as a social panacea by the temperance movement, who released tracts including Practical Hints on Coffee Stall Management, and Other Temperance Work for the Laity (1886). In 1880 Emma Cons, the temperance campaigner and theatre manager transformed what is now the Old Vic Theatre in Waterloo into ‘Royal Victoria Coffee Palace & Music Hall’ in an effort to provide wholesome, alcohol-free entertainment for South London’s working classes.

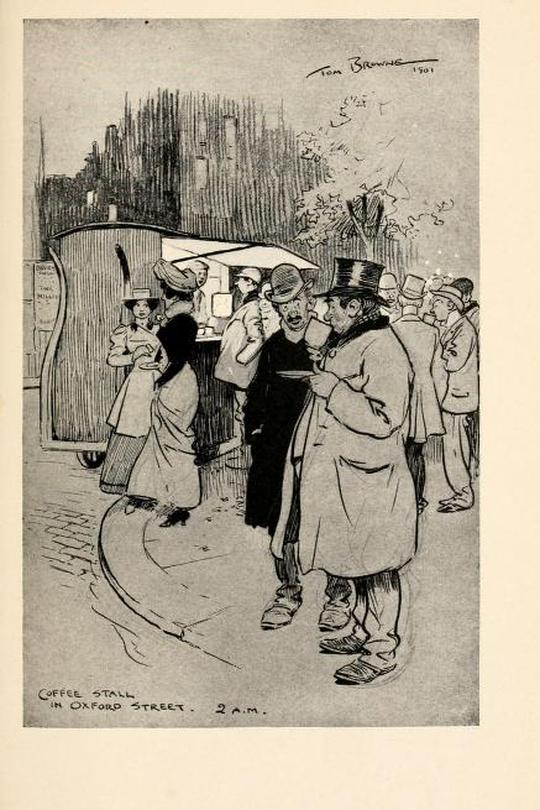

By the early twentieth century relatively favourable discourse surrounding this beverage seems to have shifted significantly, especially with regard to the street selling of coffee. Commentators now claimed to be able to identify an ‘intimate link’ between ‘coffee-stalls and crime’. In The Night Side of London (1902) Robert Machray argued that these sites constituted training grounds or mustering points for ‘graduates’ of criminality, who would then go on to enlist in gangs and terrorize the city. The fear of this swelling army of lawbreakers may have been aggravated by the knowledge that many of those who attended South London’s coffee stalls were decommissioned and unemployed soldiers who had returned home after the South African Wars. However, the calm and congenial mood depicted in Tom Browne’s sketch (included below) seems to counteract Machray’s agitated response to this setting, and introduces a degree of aesthetic uncertainty into this account. On the 13th July 1900, the Member of Parliament for Battersea, John Burns, even made a speech to the House of Commons calling for tougher measures that would compel these informal premises to obtain a licence to trade. Burns argued that more ‘legitimate’ stalls should be allowed to stay open, but that existing legislation such as the 1824 Vagrancy Act, should be used to close down ‘bad’ stalls ‘that are springing up, especially where prostitutes most do congregate, which give an excuse for disorderly people to gather, and which are a centre of rows, trouble, assaults, and so forth.’

At this time, coffee stalls were also being drawn into the moral panic over ‘Hooliganism’ that had been sparked by Clarence Rook’s semi-fictional account of a roguish south London gang member in The Hooligan Nights (1899). The unwary visitor, through a process of cultural assimilation and moral contamination, risked being absorbed into this fraternity of degenerates. In the following description, the cheap and ready condiments that are wolfed down at the coffee-stall counter, seem to act as a type of catalyst for this latent strain of brutality:

The “Hooligans” at the coffee-stall absorb into their systems a couple of hardboiled eggs, eat a piece of cake, and drink a cup of coffee each, cursing very audibly as they consume the food. The meal finished, they light cigarettes, look round as if they were speculating whether there was any opening for them in the crowd, and, seeing none, they slouch away into the darkness.

Lyons clearly wanted to encourage his readership to recognise the misperceptions and assumptions upon which these reformist accounts were grounded. When a man named ‘Mr. Fothergill, M.A.’ turns up at the newspaper office where Lyons works, his nagging requests for assistance are repeatedly ignored. Fothergill has written “several small works on sociological subjects”, is “in favour of the suppression of all forms of vice by Act of Parliament” and is looking to conduct social research for a “‘How London Lives’” type publication. He is therefore eventually ‘bequeathed’ to Lyons who reluctantly takes him to South London for a ‘fish supper—wishing it might choke him—and so to Arthur’s.’ On reaching the stall, Fothergill is captivated by his new surroundings and resolves to “devote a chapter of my forthcoming volume to a survey of the history, scope, and ethical utility of this species of refectory. ‘St Boniface of the Benighted’ would, I think form a descriptive and alluring title for that feature of the work […] “‘Midnight coffee-stalls’ would do as well,” I replied, for Mr. Fothergill was rasping me.’ The self-consciously ‘literary’ reporter has to be told that he is actually meant to drink his coffee, and eventually agrees to do so only after he has utterly divorced this activity from its everyday context—it is a “system of enquiry” which has the “merits of realism.” The social investigator then begins recording his observations in a notebook while making doleful pronouncements about the deplorable moral state of the visitors to this establishment:

“The extreme disharmony of it all. The misery! The want!! The sorrow!!! The pain!!!! The sordidness!!!!! It is a surprising, pathetic, and painful spectacle. It is a spectacle such as few could witness without distress, and none without emotion. This is England at her saddest. Such a sight is calculated to make humanitarians and reformers of the most worldly men. Ah me!”

Unsurprisingly, the gathered customers who are the target of this ‘outburst of feeling’ do not respond well to being repeatedly accused of constituting a depressing ‘spectacle’ of social dysfunction and ‘disharmony.’ Lyons is consequently delighted by the masterful retort of a drayman ‘who turned suddenly and addressed the sociologist as “Toe-face.”’ Despite his appeals to the proprietor, Fothergill is unable to succeed in “putting a stop” to the protests that he has initiated, and is ultimately forced to flee the scene. The cultural milieu of the coffee stall lends itself to the destruction of Fothergill’s sense of authorial priority and highlights the bankruptcy of his sweeping moral pronouncements. The social commentator is ultimately made to feel embarrassingly out of place within this context. We are later informed that this episode explains why ‘a whole chapter in Mr. Fothergill’s lately published work is devoted to a denunciation of coffee-stalls’, that according to the author are “plague-spots upon the fair face of our metropolis.”

Despite the fact that Lyons clearly creates a pseudonymous persona for this social reformer, it is certainly possible to argue that he might have been targeting specific writers with this attack. George R. Sims had written various books focusing on the ‘social and political problems’ of the city, such as Horrible London (1889) and he edited a three volume compendium of essays entitled Living London that was published between 1901 and 1903. The third volume of this series was published a year before the second section of Arthur’s was written. It contains a short article entitled ‘London at the Dead of Night’, which was authored by Sims and that recounts the narrator’s journey from Blackfriars bridge, where ‘the belated wayfarer may for the modest sum of a halfpenny be borne drowsily to the Elephant and Castle, and go far beyond.’ Sims follows the same route as Lyons, travelling southward toward the haunts of the ‘Lambeth Hooligan’ and discovers a coffee stall populated by ‘dangerous loafers around the steaming urns and the ever attractive light.’ He then rather dismissively and abruptly states that ‘it is not advisable to study character at a coffee-stall in the middle of the night.’

In Arthur’s the adverse moral impact of the coffee stall is questioned, and this setting is generally shown to be mitigating social ills rather than inflaming them. For example, while walking in London the narrator meets a stranger who refers to himself as ‘Beaky’ and who bears a ‘distorted likeness to Benjamin Disraeli.’ Beaky was previously a comedian who went under the moniker of ‘Fred Dilnutt’ and performed in a circus troupe. After being forced to protect his friend Primrose Hopper (“’long a’ the cockernuts”) from the unwanted attentions of male admirers such as “Professor Dinwaddy, of the Electric Shocks”, Beaky’s personal safety came under threat and he was forced to walk a “trillion million billion blighted miles” with his accomplice in an effort to find work. When Lyons finds that Beaky is so hungry that he has resorted to swallowing chewing tobacco (which is giving him painful stomach cramps) he sets out with the aim of finding nourishment for this starving traveller. Lyons heads south to Arthur’s rather than going to a nearby establishment on the north bank of the Thames that he knows ‘to be horribly police-ridden.’ Having reached their destination, Beaky eats ‘seven hard-boiled eggs and half a cottage loaf’ and then begins to sing ballads that are playfully likened to ‘reliques of ancient poetry.’ Touching on his life in the circus, Beaky’s anecdotes resemble ‘a masterpiece of romantic fiction’ that is well received by the ‘charmed circle’ who have gathered at the stall. Arthur is so taken by tales about an alcoholic Kangaroo and a piebald horse, which was actually a zebra, that he feels compelled to offer ‘Mr. Dilnutt’ the post of “curate-in-charge” at the coffee stall, which the newcomer gratefully accepts.

However, the ameliorative focus then shifts to ‘Beaky’s mate’ Primrose, who has been temporarily housed by the stall’s ‘regulars’, but has as yet been unable to find a job. Arthur reminds Lyons that he must help find the girl a situation, because he has made himself responsible for these two wayfarers—“You dug the beauties up.” A ‘conspiracy of kindness’ is therefore hatched amongst Arthur’s patrons that involves Lyons appealing to a printer named Mr. Honeybunn, who has been known to employ jobless women in the past. This group begin the “work” of constructing a narrative that will ensure that Primrose constitutes what Honeybunn considers to be a “deserving” but not “too deserving’” case. Being hungry, lonely and miserable is not sufficient, and it is suggested that Primrose pretends that she has contracted “consumption” while on tramp. However, when the printer arrives, Primrose claims to have been insulted by her potential benefactor, and does not prove to be the docile supplicant for philanthropy that he has been expecting. As a result of this setback, Primrose’s friends become involved in a frantic damage-limitation exercise and the position at the printer’s is eventually secured. In Richard Rowe’s Life in the London Streets(1881), there is further evidence of the ameliorative function of the coffee stall. While on walk from Greenwich to London, Rowe chances upon one stall that is ‘tented with tarpaulin’ and whose proprietor ‘a bronzed motherly-faced woman in a man’s great-coat’ has offered shelter to a homeless girl who is ‘curled up very much like a cat.’

Humour is undoubtedly a crucial ingredient in Lyon’s story-telling technique, although it is not accurate to say that he produced ‘light’ or ‘facetious’ material. Instead his sketches bear witness to those ostensibly trivial, quotidian or ‘vulgar’ phases of urban existence where the trials and vicissitudes of city life are often brought into the sharpest focus. His stories are suffused with cockney dialect that can appear relatively obscure or outdated to the modern reader. However, it is certainly worth keeping a slang dictionary to hand and accustomizing oneself to his lyrical ingenuity and depth. This perceived coarseness undoubtedly contributed to the Circulating Libraries decision to place a ban on Lyons’ Cottage Pie: A Country Spread in 1911. This ruling seemed particularly remarkable because Cottage Pie was one of the more innocuous novels that he had produced. Important figures in the publishing industry sprung to Lyons’ defence, including Austin Harrison the editor of The English Review.

Lyon’s first novel Hookey: Being a Relation of Some Circumstances Surrounding the Life of Miss Josephine Walker(1902) originally had the subtitle A Cockney Burlesque, which the publishers Fisher Unwin may well have expurgated because it was deemed to be too lowbrow. This term ‘burlesque’ is useful one for characterizing Lyons’ style because his literature seems to have absorbed some of the linguistic exuberance and performativity of the vaudeville theatre. According to Alan Richardson this ‘dramatic sense’ and ‘gift for dialogue’ explains how Lyons was able to achieve a significant degree of success by writing several one act plays and one longer ‘Cockney war play called London Pride.’ In Arthur’s, newcomers to the coffee stall adopt dramatic names and personas that often seem to have been specifically adapted for this setting. Those visitors whose social prominence swells beneath the petrol lamps of the coffee stall (the demobbed soldier, the street trader, the labourer, the cockney ingénue) also correspond to the proletarian characters that became popular on the music hall stage during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

After a highly successful tour in America, in 1921, Charlie Chaplin returned to England to a rapturous reception from the public. The comic actor was eager to revisit parts of south London where he grew up under conditions of grinding poverty:

I had stolen away from everybody that night, and as I crossed Blackfriars Bridge and made my way towards Kennington, I saw other lights that brought back memories of my early days.

They were the lights of the coffee-stall. I turned up my coat collar and ordered a cup of coffee and a hard-boiled egg, as I had in those days when I was fighting to get a living. There was the same kindly service from the man behind the steaming urn; the same kindly feeling of sympathy and understanding among the crowd that leaned over the counter.

Chaplin retraces Lyons’ steps, and like this novelist he welcomes the sense of anonymity and camaraderie that is afforded by the ‘other lights’ of the coffee stall. Unfortunately, this retreat from celebrity is only a temporary one and the performer is soon recognized. In the 1918 film A Dog’s Life Chaplin stars as a tramp who surreptitiously steals pastries and sausages from the owner of a coffee stall (played by his brother) with the aid of a mongrel called ‘Scraps.’ This duo beat a rapid retreat when they are caught red-handed by a policeman who is then promptly knocked out by the sausage-wielding proprietor. This Punch and Judy-esque episode hints at the relative tolerance that the poorest city-dwellers were granted at the coffee stalls, but it also underlines that this was a space with a distinctly theatrical logic that had its own distinctive props and postures. Perhaps the experience of this setting where daily struggles for survival were played out, informed the distinctive vision of modern city life that Chaplin would develop through his on screen persona.

The striking relief on the cover of Arthur’s illustrates that bold and billowing costumes were an essential component of the coffee stall spectacle. This image is almost certainly based upon a specific episode that is depicted in a segment of this book entitled ‘One of England’s Heroes.’ Trooper Alfred, Arthur’s son, is located on the far right of this scene:

Alfred stood immediately beneath the great lamp of his father’s stall, and his crouching bulk, enveloped in a romantic overcoat of military pattern, stood out boldly against the darkness which surrounded it. The whole proceeding had a pleasant favour[sic] of the drama.

Next along is Primrose Hopper, Alfred’s future wife who is wearing a ‘beautiful costume in purple velvet’, a ‘profusely feathered hat’ along with a ‘rose-coloured silk neckerchief and yellow canvas shoes.’ Primrose’s friend (on the far left) is also competing for Alfred’s affections and she is clothed in a yellow blouse, a peacock hat, Alaska jewellery and is ‘perfumed like a valentine’, but it is her ‘pale brown boots’ that most transfix the narrator. ‘This beautiful creature grew—or should one say “soared”? —out of her boots like Venus rising from the waves.’

Critics frequently highlight an egalitarian or socialist tone, along with a ‘touch of the Shavian spirit’ in Lyon’s writing and it is undeniably the case that radical political beliefs had a role in shaping his literary style. However, this democratic attitude was often most convincing, when he surrendered to the peculiar dynamics of urban spaces where motley assemblages of city-dwellers were thrust into unexpected alliances. In Sixpenny Pieces (1910) the author turned his attentions to a slum doctor’s surgery in the East End and the ‘gentle murmuring press of sufferers which lays siege to it.’ This practice is occupied by the eccentric Doctor Brink, a teenage girl lodger who is inexplicably called James, an artist called Mr. Baffin (who resembles Shaw’s Higgins in many respects) and a crush of patients with a never ending supply of strange ailments:

“And if I close my eyes and touch anythink cold with me ‘ands I kin see a lot of funny green things all in front— floatin’, if you understand me, Doctor. Me ‘usband, when ’e was sowjer abroad in Dublin, ’e got the same thing, along o’ eatin’ ’ysters in a onfit state.”

The narrator meets Brink after a night out drinking and then stays at his house over night. In the morning he realizes that he has woken up in James’ bedroom after she comes in to retrieve some clothes. James finds it hard to understand the interests that have driven Lyons to visit districts where there are ‘cinders and rags and pieces of paper and battered cans and smudgy babies and hungry cats.’ The reporter denies that he shares the agenda of the ‘Meliorist’ types who have previously visited Brink, and refuses to expand upon his own motives for being there.

“Reform!” I cried, “what do I reform? Why, I don’t reform a blue-bottle.”

“But surely you’re against something or other. You must be against something! […] I could stand much from you — more than usual I mean — because you are clean shaven, and that is such a change from most of the other powerful thinkers whom one finds here in the morning.”

There are several instances in Arthur’s where Lyons is either mistaken for a social reformer or a ‘tract merchant’ who is surreptitiously seeking to convert the poor to his enlightened values. But the encounter with Fothergill shows that this author was keen to separate himself from those who set out to identify the sources of a ‘social disease’ in the city’s poorer locales.

Lyons appears to have had a vexed relationship with his own professional status. When visiting an unfamiliar suburban coffee stall it is this inscrutability and unwillingness to own up to his vocation, that ironically makes the writer particularly ‘provocative of attention.’ In a strangely inverted situation, it is the author’s ‘history’ that now comes under scrutiny from the cabmen who are gathered at the stall. This exchange develops into an elaborate game in which a bizarre series of speculative identities are proposed for this taciturn newcomer. Lyons understandably finds this experience a rather uncomfortable one and the slightly drunk coffee stall keeper after ‘breaking his philosophic silence’ has one final attempt at deciphering this mysterious character:

“What is he, then? Shall I tell you what he is, then? Why certainly. He—he is a sort of muddy vision—that’s what he is. He is a curiosity. He—he is a pore little escaped curate. Or a poor ole ghost. Or a skeleton in a ulster. There’s two of ’im. ’E’s all pink.”

It is clear that the narrator’s eccentric identity is largely accepted amongst the customers of Arthur’s, although this ‘muddy’, lurking presence does occasionally unsettle his fellow coffee-drinkers. For instance, when Lyons witnesses Primrose and Alfred’s boisterous ‘spring-time courtship’ (depicted on the spine of the novel) he remains ‘safe from observation’ by following them on the opposite side of the road for some distance. Lyons resembles the filmmaker who is determined to document the romantic assignations and unforeseen alliances that unfold at the coffee stall, but who would feel uncomfortable about the prospect of experiencing such dangerous intimacy for himself. In spite of this, he is often forced to participate in events and therefore unwontedly to influence the plot of his novel as it unfolds.

An uneasy tension exists between the ‘night-seeker’, sometimes referred to as ‘Algy’, who merely embodies one of Arthur’s less conspicuous clients, and ‘A. Neil Lyons’ the ambitious author who is seeking to preserve his professional dignity while faithfully representing the lives of those around him. Indeed, ultimately Lyons finds that his cover is blown when Arthur questions the narrator about the occupation that he has evidently been attempting to conceal:

“And what is this I ’ear in regards to you putting me into print? Nice idea of friendship you ’ave got, to be sure! […] But what you’ve really come for is to find some ’istory or another for to shove into print. Well, well, there—I won’t bear no ill-will. We all got to live, even a powit.”

These comments dexterously draw attention to the mercantile interests that potentially lie behind a friendship that Lyons would rather understand as being uncontaminated by his role as jobbing writer. Arthur refuses to let his companion hold onto the illusion that the coffee stall embodies a submerged utopian refuge. This space is not hidden away from the ethical quandaries experienced by the grubbing reporter, for whom human companionship is merely a necessary part of obtaining material ‘to shove into print.’

Lyons was not the first to recognize the potential of the coffee stall to produce useful copy. In Unsentimental Journeys; or Byways of the Modern Babylon(1867) James Greenwood records returning home on a bus from the Strand and arriving in Angel ‘about thirty minutes before midnight’. There he witnesses the keeper of a coffee booth dragging this vehicle along the road with his wife and eventually stationing it on ‘piece of waste ground in front of a tavern.’ After the stall is set up, and his wife has left, Greenwood enters into to conversation with this proprietor.

“Ah, I have often thought what a remarkable book it would make if I was to write down all the queer customers I serve.”

I, myself, could not help reflecting on the exceedingly remarkable volume my friend was capable of producing under the circumstances. Still, the notion, in a limited sense, was not without its attractions, and before I bade the coffee-man adieu I had arranged a little plan with him.

Greenwood’s method for exposing the coffee stall’s ‘remarkable’ hidden narratives is pragmatic and straightforward. He hands the proprietor a pencil along with some leaves of a notebook and asks him to record the events that unfold throughout the night. Greenwood then collected these transactions in the morning, and transferred about a thousand words of this testimony into his final publication. However, we are not told whether this freelance correspondent was offered any remuneration in return for his services.

Coffee stalls could appear at night and then vanish without a trace during the daytime. However, Lyons did not seek to demonize this inherently transient space, which seemed to absorb London’s chaotic contingency, but where it was necessarily possible to ‘witness a real night change.’ He recognized that these sites accommodated ephemeral histories that instead of being overtaken by shadows and swallowed up by the ‘Night Side’ of the streets, were allowed (perhaps only for an instant) to stand out ‘boldly against the darkness.’ These stalls provided a refuge for those elusive characters that were the inhabitants of a shifting, rootless and undocumented city. Be that as it may, Lyons refuses to fix, locate or ‘place’ Arthur’s for his readership. This space is ‘found out’ only by those who have become hopelessly stranded on the streets of south London and for whom the ‘ever attractive light’ of the coffee stall is a blessed and indispensible relief.

Peter Jones is working towards a PhD at Queen Mary that explores literary responses to socially marginal, transient and ‘surplus’ populations in nineteenth-century London. His research analyses the cultural dynamics of informal street trades that dealt with the city’s waste and detritus. In April 2012 Peter helped to set up the Literary London Reading Group, which meets at Senate House – details here.

References and Further Reading

NOVELS AND SHORT STORY COLLECTIONS BY A. NEIL LYONS

Hookey: Being a Relation of Some Circumstances Surrounding the Early Life of Miss Josephine Walker, London: Fisher, Unwin, 1902,

Matilda’s Mabel, London: Grant Richards, 1903,

Arthur’s: The Romance of a Coffee Stall, London and New York: John Lane, 1908,

Cottage Pie: A Country Spread, London and New York: John Lane, 1911,

Clara: Some Scattered Chapters in the Life of a Hussy, London and New York: John Lane, 1912,

Simple Simon: His Adventures in the Thistle Patch, London and New York: John Lane, 1914,

Kitchener Chaps, London and New York: John Lane, 1915,

Moby Lane and Thereabouts, London and New York: John Lane, 1916,

A Kiss From France and Some Soldiers From Everywhere, London and New York: Hodder and Stoughton, 1916,

A London Lot (based on London Pride, the play by Gladys Unger and A. Neil Lyons), London and New York: John Lane, 1919,

A Market Bundle, London: Thornton Butterworth, 1921,

Fifty-Fifty: A Blend of Old and New (Tales), London: Thornton Butterworth, 1923,

Love us All: Some Exclamatory Notes, London: Thornton Butterworth, 1924,

A. Neil Lyons, (a selection of his stories) intro. by F.H. Pritchard, London: Harrap, 1929,

Tom, Dick and Harriet, London: Cresset Press, 1937.

OTHER SOURCES

Julian Franklyn, The Cockney, A Survey of London Life and Language, London: Andre Deutsch Ltd., 1953,

James Greenwood, Unsentimental Journeys: Or, Byways of the Modern Babylon, London: Lock and Tyler, 1867,

Robert Machray, The Night Side of London, illus. by Tom Browne, London: John Macqueen, 1902,

Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, 4 vols. London: Harper and Brothers, 1851-1861

Deborah Mutch (ed.), British Socialist Fiction, 1884-1914, 5 vols., London: Pickering and Chatto, forthcoming Sept. 2013, http://www.pickeringchatto.com/1107-9781848933576-british-socialist-fiction-1884-1914

Alan Richardson, ‘A Note on A. Neil Lyons (1880-1940)’, ELT, 23 (1980), 208-214,

David Robinson, Chaplin: His Life and Art, London: Penguin, 2001,

Clarence Rook, The Hooligan Nights, London: Grant Richards, 1899,

Richard Rowe, Life in the London Streets, Or Struggles For Daily Bread, London: J.C. Nimmo and Bain, 1881,

G.R. Sims, Horrible London, London: Chatto and Windus, 1889,

—-, Living London, 3 vols., London: Cassell and Company, 1901-1903,

William H. Ukers, All About Coffee, 2nd edn., New York: The Tea & Coffee Trade Journal Company, 1935

Martha S. Vogeler, Austin Harrison and the English Review, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008

Editor’s note: Syd’s coffee stall in Shoreditch closed for good in December 2019 https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/syds-coffee-stall

All rights to the text remain with the author.