Eliza Cubitt

To London Town is the final instalment in Arthur Morrison’s ‘East End Trilogy’. Together with Tales of Mean Streets (1894) and A Child of the Jago (1896), it was intended to provide a picture of working-class life in the East End of London at the end of the nineteenth century. Morrison’s note that precedes the novel states:

I designed this story, and, indeed, began to write it, between the publication of Tales of Mean Streets and that of A Child of the Jago, to be read together with those books: not that I pretend to figure in all three – much less in any one of them – a complete picture of life in the eastern parts of London, but because they are complementary, each to the two others.

To London Town in fact leaves a very different impression to the two other works. In this novel, unlike the unremitting violence and struggle for survival portrayed in A Child of the Jago, or the desolation, monotony and ‘utter remoteness from delight’ portrayed in Tales of Mean Streets, Morrison portrays London as a place of infinite possibility, hopefulness, and even romance. In the comical depiction of a close-knit society, it has some similarities of tone to Henry Woodd Nevinson’s Neighbours of Ours (1895), but it takes a more romantic line in assigning the love story to the central character, and depicting London as a Dick Whittington–esque place of opportunity. Contemporary reviews appreciated the position of To London Town alongside Morrison’s previous works, as this review from the Bookman (Nov. 1899) shows.

To London Town in fact leaves a very different impression to the two other works. In this novel, unlike the unremitting violence and struggle for survival portrayed in A Child of the Jago, or the desolation, monotony and ‘utter remoteness from delight’ portrayed in Tales of Mean Streets, Morrison portrays London as a place of infinite possibility, hopefulness, and even romance. In the comical depiction of a close-knit society, it has some similarities of tone to Henry Woodd Nevinson’s Neighbours of Ours (1895), but it takes a more romantic line in assigning the love story to the central character, and depicting London as a Dick Whittington–esque place of opportunity. Contemporary reviews appreciated the position of To London Town alongside Morrison’s previous works, as this review from the Bookman (Nov. 1899) shows.

The reproaches sometimes cast at Mr Morrison that his ‘Tales of Mean Streets’ and his ‘A Child of the Jago’ gave a one-sided and a very miserable account of East London life, must now cease. It was not a wanton delight in gloom that made him write so harshly of existence in the wildernesses of bricks and mortar. He writes his report of life in chapters, and not in one alone can he tell the ultimate truth.

The novel begins in the centre of Epping Forest, a place of exquisite natural beauty, which is threatened by the rapid eastward expansion of London. Grandfather May’s collection of butterflies, from which he makes his living and supports his widowed daughter-in-law and her two children, is threatened by this change:

London grew and grew, and washed nearer and still nearer its scummy edge of barren brickbats and clinkers. It had passed Stratford long since, and had nearly reached Leyton. And though Leyton was eight miles off, still the advancing town sent something before it – an odour, a subtle principle – that drove off the butterflies.

After May’s mysterious death from ‘a bad wipe over the head’, the family leave Epping Forest and move back to London, where Mrs May sets up a small chandler’s shop in their old neighbourhood of Blackwall. Although we still know relatively little about the life of Arthur Morrison, we can see many similarities between Morrison’s youth and that of Johnny May, depicted in the novel. Morrison’s father was an engine fitter who died when Morrison was young. His mother then supported Morrison and his younger siblings by running a haberdashery shop in Grundy Street, Poplar, which neighbours Blackwall. In the novel, Johnny May, aged fourteen and the hero of the piece, is apprenticed to the engineers’ firm Maidment and Hurst’s, in whose service his father died in an industrial accident. Through perseverance, assiduity and enterprise, the small family are able to make their way in life. London, which seemed threatening at first, becomes a place of infinite possibility for Johnny, his mother and his little sister Bessy.

As in all Morrison novels and stories, To London Town has a very precisely delineated location. Johnny May explores in intimate detail the streets surrounding Harbour Lane and Shipwright’s Row, discovering a London somewhat decayed since his parents moved away from the city when he was a young child. Nevertheless, there is wonder there, hopefulness, and a true sense of community, which, in Harbour Lane, is expressed through the comical and ritualistic trade of paint:

As thus, to make a simple case: “’Ullo, Bill, what about that pot o’ paint?” “Well, I was goin’ to bring it round to-night.” “All right. But don’t bring it to me – take it to George. Ye see, I owe Jim a bit o’ paint, an’ ‘e owes Joe a bit, an’ Joe owes George a bit. So that’ll make it right all round. Don’t forget!” With many such arrangements synchronising, crossing and mixing with each other, and made intricate by different degrees and manners of debit and credit between Bill and George and Jim and Joe, the unlikely subject of paint became involved in a mathematical web of interest.

Like Morrison’s Jago, this place operates on its own terms, but here the terms are friendly, carefully defined and universally understood. As Ken Worpole has suggested in Dockers and Detectives, ‘London’s dockers and lightermen inhabited rituals and customs’ which were local and entirely unique. When a neighbour pops his head over the back wall and says to Mrs May, ‘’Bit o’ red paint any use to ye?’ the family know they are accepted. Kindness manifests itself in the secret aid of a neighbour, Long Hicks, with the painting of Mrs May’s shop front – he comes secretly in the night to paint the bits of cornice that Johnny isn’t tall enough to reach.

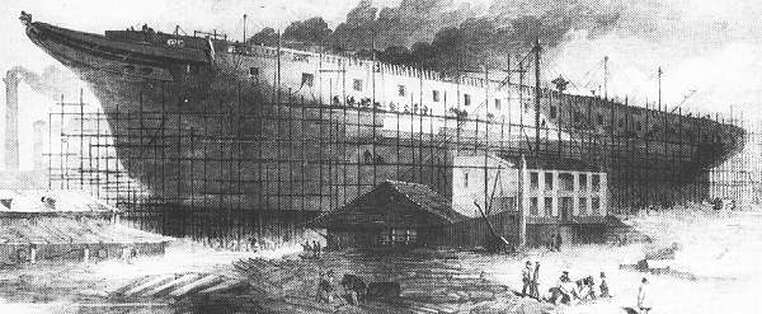

As Johnny May explores his surroundings, we see that this is a London utterly unlike that depicted in Morrison’s A Child of the Jago. The Blackwall of the late-nineteenth century was a bustling place of manufacture and trade, as the Reverend Harry Jones wrote in 1875:

The neighbourhood of the River and the Docks displays the paraphernalia of the sea and shore. Slops and sextants, deck-boots and telescopes, are offered in what, to an outsider, appears a superfluous abundance along the bank of the Thames east of the Tower. There, too, may be found rope-walks and sail-lofts. Many of the manufactures and trades associated with seafaring life are carried on in our part of the city. They are indeed common to all seaports; but of these London is the largest, and thus they abound among us. (From East and West London., 1875, accessed at http://www.mernick.org.uk/thhol/eastwest2.html#blackwall)

Shipbuilding in the area began to decline in the 1870s, but the area remained populated by skilled workers and many engineers who worked on the new graving dock, which opened in 1878. Charles Booth’s Poverty Maps of 1898-99 show the area around Blackwall to be pink and purple which in Booth’s classification meant that the area ranged from ‘Fairly comfortable’ to ‘Mixed – some comfortable, others poor.’ Much of the Nichol in Bethnal Green (which Morrison fictionalised as the ‘Jago’ slum), was colour-coded by Booth and his researchers in black and dark blue, indicating ‘chronic want’ and a ‘Vicious, semi-criminal’ population.

For Morrison, the area around Blackwall is, in spite of some decline, a place that remains drenched in honourable and romantic history. It is a place in which kings and heroes have lived and died, and in which they are remembered, as Johnny’s explorations show:

He came upon basins filled with none but sailing-ships, and here the masts were as tall and fine as ever, stayed with much cordage, and had their yards slung at a gallant slope, like the sword on Sir Walter Raleigh’s hip. And at Blackwall Stairs, looking across the river, stood an old, old house that Johnny stared at for minutes together: a month or two later he heard the tradition that Sir Walter Raleigh himself had lived there. It was first of a row of old waterside buildings, the newest of which had looked across, and almost fallen into, the river, when King George’s ships had anchored off Blackwall – and King Charles’s for that matter.

Morrison’s treatment of the ‘Institute’ in To London Town also shows that this novel is about opportunity and self-improvement. The characters in To London Town are far more sensitively portrayed than in A Child of the Jago, where people are so affected by their surroundings and desperate poverty that they consider only how to get food, drink and money. In To London Town they seek advancement, fulfilment, love. Institutions so mocked by Morrison in A Child of the Jago and the sketch ‘A Street’ are here promoted as tools for self-advancement, though Morrison still critiques them: ‘there were sometimes superior visitors from other parts, oozing with inexpensive patronage, who spoke of Johnny and his companions as the Degraded Classes, who were to be Raised from the Depths.’

Unlike Dicky Perrott in A Child of the Jago, Johnny seeks out learning – whereas Dicky himself never attends Father Sturt’s boxing ring or church. In To London Town, the interfering and condescending West-Londoners who go ‘slumming’ by visiting the Institute unwittingly aid Johnny and his beloved Nora in instigating a dance at which they first become acquainted. Morrison’s ire against these places is, in this novel, absorbed in comedy. Johnny, in love, is:

Altogether becoming a sad young fool, such as none of use ever was in the like circumstances. (…) But an angel – two angels, to be exact, both of them rather stout – came one night to Johnny’s aid. They came all unwitting, in a cab, being man and wife, and their simple design was to see for themselves the Upraising of the Hopeless Residuum. They had been told, though they scarce believed, that at the Institute, far East – much farther East than Whitechapel, and therefore, without doubt, deeper sunk in dirt and iniquity – the young men and women danced together under regular ball-room conventions, neither bawling choruses, nor pounding one another with quart pots. It was even said that partners were introduced in proper form before dancing – a thing so ludicrous in its incongruity as to give no choice but laughter. So the doubters from the West End (it was only Bayswater, really) took a cab, to see these things for themselves.

In his depiction of the romance between Nora and Johnny, Morrison neither sensationalises nor mocks Nora’s appearance – ‘Her hair was neither golden nor black, but simple brown like other people’s, and her eyes were mere grey; yet Johnny dreamed.’ There is a beauty in ordinariness in this novel, quite unlike the ‘fairyland of horror’ which the critic H.D. Traill saw in A Child of the Jago, the ‘sordid uniformity’ of Tales of Mean Streets, or the ‘attraction of repulsion’ which Henry Woodd Nevinson described in accounting for the lure of the East End, and the women of the East End, for him.

When they are prevented from going to the dance together by Nora’s mother pawning her dress, they instead take a walk around the docklands. Unlike Dickens, they don’t rely on coincidence, but Nora modestly suggests that ‘If she took a walk, she might go in such and such a direction, passing this or that place at seven o’clock, or half-past. That was all.’ This is, therefore, a uniquely realist romance, in which neither chance nor wealth, but hard work and self-help, raise the hero so that he can fight his foes, and go bravely ‘into the world of new adventure.’

Eliza Cubitt is a PhD student at University College, London, writing on Arthur Morrison and late nineteenth century realism. She writes a blog: thisstrangecity.blogspot.com

Blackwall today

The area round Blackwall is today towered-over by the enormous office blocks of Canary Wharf. There are still some streets that maintain the community feel, such as Coldharbour with the historical Gun Pub facing over the water, and St Lawrence Cottages (pictured above), which share the bright colours of ‘Harbour Lane’. Weekly commuters, however, populate many of the nearby flats, so that at weekends the area has a desolate feel.

The area round Blackwall is today towered-over by the enormous office blocks of Canary Wharf. There are still some streets that maintain the community feel, such as Coldharbour with the historical Gun Pub facing over the water, and St Lawrence Cottages (pictured above), which share the bright colours of ‘Harbour Lane’. Weekly commuters, however, populate many of the nearby flats, so that at weekends the area has a desolate feel.

Near Blackwall DLR station are tower blocks which represent some of the less appealing designs of twentieth-century social housing in London. Like the houses Morrison rails against in To London Town, these flats are unrelieved by variety.

Their likeness each to the next gives them the aspect of impenetrable barracks, whereas those described in Harbour Lane are each reached from a different level – some by the area stairs, some by steps to the front door, some at street level – and the gardens are alternately to the front and back of the houses, so that Harbour Lane is unique and varied.

…and Morrison’s birthplace

Grundy Street in Poplar, which Stan Newens’ diligent research has identified as Morrison’s birthplace, was mostly destroyed in the Blitz. Elizabeth Row (above) sits where Morrison’s house would have been (number 4).

Grundy Street in Poplar, which Stan Newens’ diligent research has identified as Morrison’s birthplace, was mostly destroyed in the Blitz. Elizabeth Row (above) sits where Morrison’s house would have been (number 4).

The former pub in the right-hand corner of the picture below is possibly the only building on the street that has survived since Morrison’s time. From this view facing south from Elizabeth Close we can see that Morrison, like Johnny, would have been able to see the masts of ships from his street.

Further Reading

Keating, Peter J. (ed.), Working-class Stories of the 1890s (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971)

Koven, Seth, Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London (Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2004)

Nevinson, Henry W., Neighbours of Ours (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Kent and Co. Limited, 1895)

Newens, Stan, Arthur Morrison: The Novelist of Realism in East London and Essex (Loughton: The Alderton Press, 2008)

Morrison, Arthur, A Child of the Jago edited by Peter Miles (Oxford World’s Classics, 2012)

– Tales of Mean Streets (London: Faber, 2008)

– The Hole in the Wall (London: Faber, 2008)

– To London Town (London: Methuen and Co., 1899)

Worpole, Ken, Dockers and Detectives (London: Five Leaves Press, 2008)

All rights to the text remain with the author. All recent photos by Eliza Cubitt.