Andrew Whitehead

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

George Gissing, a northerner, came to London as a social outcast. He was a stranger in an immense city which he explored ceaselessly, which absorbed his intellectual energy and fed his creativity, and about which he had little good to say.

The London of The Nether World is grim, sulphurous and suffocates the human spirit. Gissing’s great novel of working class Clerkenwell has little of the picaresque humour of Dickens’s jaunts into London slums. It is not a work of social reform, for while the author’s anger sears through his story, it is burdened by a despairing resignation rather than a prescription to achieve change.

All the most obvious remedies – political radicalism, philanthropy, self-help, slum clearance – are tried during the course of the novel and found wanting. Even in Gissing’s bleak underworld there are good people with noble motives, yet the finest of his characters still find their lives crimped and their aesthetic senses blunted in the brutal snare of poverty and exploitation.

The novel’s title has two meanings. It is the out of view, out of mind universe of the urban poor. Almost every character in The Nether World has his or her roots in the working class, and the rules and rhythms of their lives are tellingly different from those of the novel’s readers. ‘In the upper world a youth may “sow his wild oats” and have done with it;’ Gissing observes, ‘in the nether, “to have your fling” is almost necessarily to fall among criminals.’

It is also the hellish world of the dead. Gissing invests his London with a stygian gloom. An incidental character, Mad Jack, a crazed itinerant preacher, gives voice to this metaphor while reciting a message received in a vision: ‘”… There is no escape for you. From poor you shall become poorer; the older you grow the lower you shall sink in want and misery; at the end there is waiting for you, one and all, a death in abandonment and despair. This is Hell – Hell – Hell!”’ The location of his prophecy is the most infernal of Gissing’s slums, Shooter’s Gardens, a ‘winding alley’, a ‘black horror’, possessed by ‘filth, rottenness, evil odours’, where each room houses a separate family, and where wife beating, drunkenness and petty crime are the order of things. Yet most of the inhabitants prefer Shooter’s Gardens to the model lodgings nearby; ‘here was independence, that is to say, the liberty to be as vile as they pleased.’

The story of The Nether World concerns Michael Snowdon’s increasingly obsessive determination to use the wealth with which he returned from the colonies to help London’s poor. His kind-hearted granddaughter, Jane, is raised modestly, and with the intention that she will execute her grandfather’s philanthropic ambitions. Sidney Kirkwood, a working man of integrity, is enlisted in the venture. A series of contrivances which owe much to Victorian melodrama – the plot includes an unsigned will, disguised identities, chance encounters, veiled faces, a scheming lawyer and even the lure of the stage – deprive Jane of her inheritance. She cannot achieve her purpose, though she succeeds in touching people’s lives simply by the quality of her character. Sidney Kirkwood and Jane Snowdon come across as honourable but insipid characters. In true Gissing style (there is something of the author in this) they are confined by a sense of duty and responsibility. They are soul mates, but cannot live their lives together.

The great rivals Clem Peckover and Pennyloaf Candy are more memorable characters; two women who would not be out of place in ‘Eastenders’. There is a touch of Dickens about them, not least in their names. Pennyloaf, a seamstress, is a brutalised, feckless but good-natured inmate of Shooter’s Gardens. Clem, from a slightly less squalid slum in Clerkenwell Close, is earthy, coarse and cunning. They compete for the affections of the ne’er-do-well Bob Hewett. Surprisingly, he chooses Pennyloaf, and the couple spend their wedding day, a bank holiday, on an outing to Crystal Palace – where Clem and her friends are also enjoying a day out. The grounds are packed. There’s a band, coconut shies, high tea, fireworks, and (for Bob, and many others) plenty of drink. Gissing had taken trouble to spy out his landscape. ‘What a day I had yesterday at Crystal Palace!’, he commented to his sister. ‘I brought back a little book full of scribbled notes. You will read it all some day.’ And there it is in The Nether World, a ‘great review of the People’:

See how worn-out the poor girls are becoming, how they gape, what listless eyes most of them have! The stoop in the shoulders so universal among them merely means over-toil in the workroom. Not one in a thousand shows the elements of taste in dress; vulgarity and worse glares in all but every costume. … Mark the men in their turn: four in every six have visages so deformed by ill-health that they excite disgust; their hair is cut down to within half an inch of the scalp; their legs are twisted out of shape by evil conditions of life from birth upwards. Whenever a youth and a girl come along arm-in-arm, how flagrantly shows the man’s coarseness!

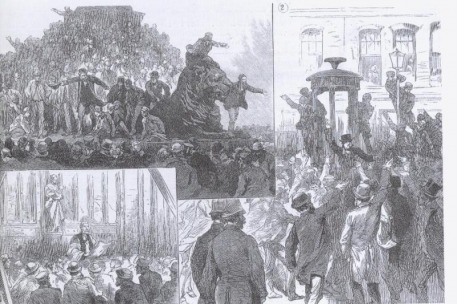

For Clem and Pennyloaf, the bank holiday outing to Crystal Palace ends in the spectacle of a brawl on Clerkenwell Green. ‘Pennyloaf flew with erected nails at Clem Peckover. It was just what the latter desired. In an instant she had rent half Pennyloaf’s garments off her back, and was tearing her face till the blood streamed. Inconsolable was the grief of the crowd when a couple of stalwart policemen came hustling forward, thrusting to left and right, irresistibly clearing the corner.’ For Gissing, as for his imaginary onlookers, the brutalism of the urban poor was a spectacle, though one that he found profoundly sad rather than exciting.

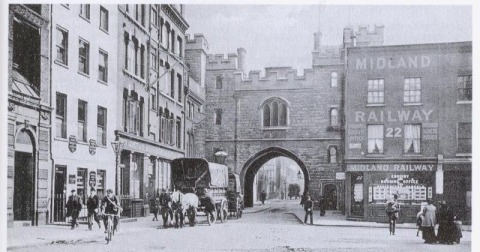

An early review of The Nether World described George Gissing as ‘a modern Dante’ – a particularly prescient comment. Gissing, a classicist at heart, had read Dante attentively as a means of learning Italian. ‘Ye Gods, what glorious matter!’, he declared. It’s probably where the novel’s title came from. The phrase ‘the nether world’ appears in Henry Cary’s hugely influential translation of Dante, with which Gissing was familiar. He was not the first to make the association between Dante’s realm of the tormented and the streets and courts of Clerkenwell. A local clergyman had, in the mid-1880s, likened the noises emanating from the deep trench built for the underground railway to ‘the shrieks and groans of the lost souls in the lowest circle of Dante’s Inferno’. Perhaps Gissing stumbled on a similar analogy; quite possibly, he borrowed loosely from the newly published parish history in this and other regards.

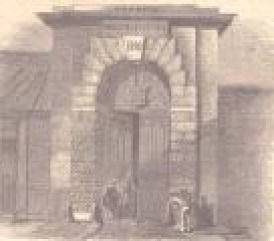

Hellish imagery and references to death set the tone from the opening pages. The story starts as the ageing Michael Snowdon, in search of his family, walks past the graveyard of St. James’s, Clerkenwell, to the walls of the Middlesex House of Detention. He stops to glance at a nightmarish effigy above the prison gateway. ‘It was the sculptured counterfeit of a human face, that of a man distraught with agony. The eyes stared wildly from the sockets, the hair struggled in maniac disorder, the forehead was rung with torture, the cheeks sunken, the throat fearsomely wasted, and from the wide lips there seemed to be issuing a horrible cry.’ (The jail was much as Gissing describes, though he can have had only indirect knowledge of the tormented face above the gateway which appears to have been removed in the 1840s). The Peckover household nearby, introduced in the first chapter, is ‘dark and cavernous’ and home to a corpse awaiting burial. Clem has been reared in the ‘putrid soil of that nether world’. The book ends in another cemetery, at Michael Snowdon’s grave at Abney Park in Stoke Newington. The recurring refrain is of a populace trapped, entombed, in a cycle of suffering.

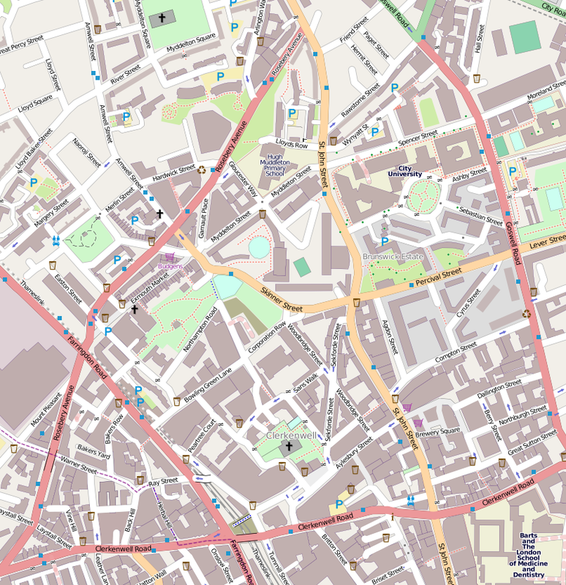

There’s an inescapable sense that Gissing alighted on his setting and theme and then populated the story, rather than the other way round. As a result, The Nether World’s depiction of the urban environment is more convincing than its account of those who dwell in it. The underworld Gissing describes is very circumscribed. Much of the action takes place within a quarter-of-a-mile of the opening scene on Clerkenwell Green, and almost all within a mile or two. He is precise in his topography, as if this exactness demonstrates the authenticity of his urban landscape. The routes taken by his ever perambulating characters are set down in detail. They are always on the move, though – until the closing sections of the story – they rarely move far. Dozens of street names are mentioned, and Shooter’s Gardens is the only important setting which can’t be found in a gazetteer. The word ‘Clerkenwell’ appears seventy-four times.

Most of Gissing’s fiction is imbued with a powerful sense of London. His novels stretch north and south of the river, from inner city tenements to the newer middle-class suburbs. London is not simply the setting, but a wellspring of his creativity, and while the urban panorama he offers is unsettling, he provides a more compelling sense of the late-Victorian city than any other contemporary novelist. That is in part because Gissing lived among the people he wrote about. He had married into the underworld, and knew the poorer parts of the city more intimately than most of its chroniclers.

George Gissing moved to London as a nineteen-year-old in the autumn of 1877. He was a Yorkshireman, born in Wakefield and northern educated, a product of the provincial middle class. By the time he came south, his life was in a groove from which he could not, or would not, escape. He had been expelled from Owen’s College in Manchester, where he had proved an exceptional student, for stealing money and had served five weeks in jail. He remained haunted by that disgrace. The theft was to help support a young Manchester prostitute, Nell Harrison, who became Gissing’s wife, and with whom he endured a miserable few years in London garrets – not themselves slums of the Shooter’s Gardens kind, but uncomfortably close vantage points. That tragic relationship tainted him, and provided much of the fire and fury in his early work. Gissing’s five novels of the London poor, of which The Nether World was the last, the bleakest and the most accomplished, were all the product of his first decade or so in the city – written while living with Nell, during their uneasy separation, or amid the catharsis of her drink-ridden decline.

‘I have a book in my head which no one else could write’, George Gissing confided to his sister in 1886, ‘a book which will contain the very spirit of London working-class life.’ Nell Harrison’s death two years later provided the impulse behind the novel that most lived up to his goal. She succumbed to what may well have been syphilis at the age of thirty. Gissing went to her room in a dingy lodging house in Lambeth to see the body, and recorded the scene in his diary:

Linen she had none; the very covering of the bed had gone save one sheet and one blanket. I found a number of pawn tickets, showing that she had pledged these things during last summer, – when it was warm, poor creature! All the money she received went in drink …

She lay on the bed covered with a sheet. I looked long, long at her face, but could not recognize it. It is more than three years, I think, since I saw her. And she had changed horribly. …

Came home to a bad, wretched night. In nothing am I to blame; I did my utmost; again and again I had her back to me. Fate was too strong. But as I stood beside that bed, I felt that my life henceforth had a firmer purpose. Henceforth I never cease to bear testimony against the accursed social order that brings about things of this kind. I feel that she will help me more in her death than she balked me during her life. Poor, poor thing!

Gissing had been toying with a novel set in Clerkenwell. ‘I have something in hand which I hope to turn to some vigorous purpose’, he wrote to Thomas Hardy in the summer of 1887, ‘a story that has grown up in recent ramblings about Clerkenwell, – dark, but with evening sunlight to close.’ Prior to Nell’s death, repeated attempts to embark on a fresh book had proved stillborn. Within three weeks, Gissing has begun to write The Nether World and it took just four months to complete.

‘It is far from finished yet, but I am satisfied on the whole with the completed parts’, Gissing told his sister-in-law in April 1888. ‘It deals exclusively with the lower classes’. This unrelenting focus on the impoverished sets The Nether World apart from his other novels. Many of his books, before and after, concern the chains of social convention, and feature men and women who straddle social classes or are caught awkwardly between them. But here, he makes a working man the central character – albeit one who bears some traits in common with his creator. As he set to work, Gissing returned again and again to the streets he had chosen for his story. ‘Evening spent in Clerkenwell, wandering’ he jotted in his diary. In the following weeks, there are similar entries: ‘Morning spent in Clerkenwell’; ‘Good Friday. Morning in Clerkenwell’; ‘In evening to Clerkenwell Green’.

Gissing never lived in Clerkenwell, but some of his London homes were strolling distance away. George and Nell took refuge in a succession of drab rented rooms in unfashionable districts of inner London. One of these was at 5 Hanover Street in Islington, just north of City Road and backing on to the Regent’s Canal. The house is now 60 Noel Road. They moved there in November 1879 – about the moment that the story told in The Nether World opens – and stayed for over a year. The street is described in the novel as ‘a quiet byway … Squalor is here kept at arm’s length’. Michael Snowdon and his granddaughter take lodgings there, and it becomes one of the novel’s principal venues – a level or two above the grim depths of Gissing’s underworld just to the south in Clerkenwell.

The area that he alighted upon as his setting, a densely populated locality squeezed between Islington, Holborn and the City, was by the 1880s home to hardly anyone but the lower classes. ‘For some years many of the well-to-do residents of the parish have been gradually leaving their houses, which become occupied by a poorer class of people, many of the houses which were formerly held by one family, being now let to several’, reported the local Medical Officer of Health in 1883.

Clerkenwell had for a century or more been associated with highly skilled artisan trades, watchmaking in particular, but also jewellery and precious metal work, and specialist printing, bookbinding and furniture trades. ‘Here every alley is thronged with small industries’, records the novelist, ‘all but every door and window exhibits the advertisement of a craft that is carried on within.’ By the 1880s, standardisation and mechanisation were making craft skills redundant, forcing many who had once enjoyed high wages and status to take on any work they could find.

Gissing reflects the pain and dislocation of the declining years of artisan inner London, and performs a task few of his contemporary novelists were sufficiently confident to attempt – taking the reader inside the workplace. Bob Hewett works in a die-sinking workshop making moulds. For Bob’s father, Gissing explains, ‘it was no slight gratification that he had been able to apprentice his son to a craft which permitted him always to wear a collar’ – though Gissing observes that die-sinking ‘is not the craft it once was; cheap methods, vulgarising here as everywhere, have diminished the opportunities of capable men.’ Hewett junior uses his skills to make counterfeit coins. Hewett senior, once a self-employed cabinet maker, is reduced to responding to a newspaper advert for an odd-job man paying a paltry fifteen shillings a week, and even then finds himself in a melee of 500 desperate jobseekers. His friend, Sidney Kirkwood, is employed as the novel opens as a jewellers in St John’s Square, ‘amid the squalid and toil-infested ways of Clerkenwell’, and later moves home to a room ‘at the top of a house in Red Lion Street, in the densest part of Clerkenwell, where his neighbours under the same roof were craftsmen, carrying on their business at home’.

Clem Peckover and Jane Snowdon are for a while workmates at ‘Whitehead’s’, an artificial flower factory hidden away in the back streets of Clerkenwell. ‘Here at busy seasons worked some threescore women and girls, who, owing to the nature of their occupation, were spoken of by the jocose youth of the locality as ‘Whitehead’s pastepots’.’ Gissing’s account of the work process and the rhythm of the day suggests that he took trouble to find out about some such factory. If so, he seems to have been impressed by the working women he encountered. ‘With few exceptions, they were clad neatly; on the whole, they plied their task with wonderful contentment.’

The transition from a proud, craft-based economy to attic workshops for those with skills still in demand, and casualised labour for the rest, is captured in one of the novel’s most celebrated and vivid passages.

It was the hour of the unyoking of men. In the highways and byways of Clerkenwell there was a thronging of released toilers, of young and old, of male and female. Forth they streamed from factories and workrooms, anxious to make the most of the few hours during which they might live for themselves. …

… In Clerkenwell the demand is not so much for rude strength as for the cunning fingers and the contriving brain. The inscriptions on the house-fronts would make you believe that you were in a region of gold and silver and precious stones. In the recesses of dim byways, where sunshine and free air are forgotten things, where families herd together in dear-rented garrets and cellars, craftsmen are for ever handling jewellery, shaping bright ornaments for the necks and arms of such as are born to the joy of life. Wealth inestimable is ever flowing through these workshops, and the hands that have been stained with gold-dust may, as likely as not, some day extend themselves in petition for a crust.

There is a compassion and social concern in Gissing’s account of his underworld which alleviates a pessimism that otherwise threatens to overwhelm the reader.

At times, Gissing veers towards polemic and exaggeration, as in his description of slum housing. Shooter’s Gardens stands in a long tradition of the classic literary slum. Yet he takes the trouble to look beyond the veneer of dilapidation and overcrowding to explain how money was to be made out of bad housing. ‘This winter was the last that Shooter’s Gardens were destined to know’, he writes. ‘The leases had all but run out; the middle-men were garnering their latest profits; in the spring there would come a wholesale demolition, and model-lodgings would thereafter occupy the site.’ The role of middle-men, house farmers as they were called, in pushing up rents while allowing the buildings’ fabric to decay, and in using local political influence to obstruct the enforcement of public health regulations, was one of the main findings of the landmark Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes of the mid-1880s. Clerkenwell was one of the districts to which the Commission paid particular attention, and local clergy, landlords and school board officials – though not the slum dwellers themselves – were called to give evidence.

The Royal Commission was part of a wave of social concern about outcast London which developed from the early 1880s, reflected in the writings of concerned clerics, sensationalist journalists and social investigators. Gissing’s novels of London poverty, all products of the 1880s, were not born from the same reflex, but they fed into the same process of developing public awareness and unease about what was sometimes called (though not by Gissing) ’darkest London’. The vogue for slum novels gathered pace in the following decade, complemented by Charles Booth’s monumental and revelatory Life and Labour of the People in London, which sought to map the city’s poverty and criminality. Gissing helped set the tone for the sensationalist slum fictions of the closing years of the century, though he privately dismissed Arthur Morrison’s A Child of the Jago as ‘poor stuff’.

The clearing of the worst slums and building of model dwellings, multi-storey blocks of workers’ flats, was one of the most conspicuous responses to concern about poor housing. Many vermin-ridden rookeries met the same fate as Gissing’s Shooter’s Gardens. In the novel, Sidney Kirkwood and the Hewett family move into newly-built industrial dwellings on one of Clerkenwell’s main roads – a building which Gissing finds repulsive:

What terrible barracks, those Farringdon Road Buildings! Vast, sheer walls, unbroken by even an attempt at ornament; row above row of windows in the mud-coloured surface, upwards, upwards, lifeless eyes, murky openings that tell of bareness, disorder, comfortlessness within. One is tempted to say that Shooter’s Gardens are a preferable abode. … Barracks, in truth; housing for the army of industrialism

The dousing down of the human spirit horrifies Gissing even more than the contagion of the old courts and alleys.

If The Nether World is testimony against the ‘accursed social order’, it is also contemptuous of those who seek to overthrow it. All five of Gissing’s novels of working class London are concerned in some degree with popular politics and unbelief. When writing his first published novel, Workers in the Dawn, he described himself as ‘a mouthpiece of the advanced Radical party.’ In the early 1880s, Gissing dallied with positivism, a bookish strand within progressive radicalism. It was a brief interlude. When in 1886 he wrote Demos, subtitled ‘a story of English socialism’, he was disdainful of organised radicalism and scathing of the shallowness of socialist leaders.

If Clerkenwell’s name was known in late nineteenth century London, it was as a hotbed of working class radicalism. The district’s craftsmen had fostered a culture of artisan radicalism which still found powerful expression in the 1880s. The Patriotic Club on Clerkenwell Green (the eighteenth century building is now, appropriately, the Marx Memorial Library) was one of the most active and advanced of London’s many working class radical clubs. As the decade progressed the most energetic of the new socialist groups, the Social Democratic Federation, found an audience among less skilled Clerkenwellians for its campaigns on unemployment, housing and trade unions for the unorganised. Clerkenwell Green itself was a forum for radical oratory, and a venue of notoriously turbulent popular protests. Gissing spent a Sunday evening there in 1887, and reported back to his family in Wakefield that it was ‘a great assembly-place for radical meetings, & the like. A more disheartening scene it is difficult to imagine, – the vulgar, blatant scoundrels!

In The Nether World, the most Gissing-like character, Sidney Kirkwood, briefly embraces working class politics. His friend John Hewett, is portrayed as a more determined radical, an embittered orator, soured by the hardships endured by himself and his family:

a lean, haggard, grey-headed man, shabbily dressed, no bad example of a sufferer from the hardships he was beginning to denounce. … What would happen to the landlords of Clerkenwell if they got their due? Ay, what shall happen, my boys, and that before so very long? For fifteen or twenty minutes John expended his fury, until, in fact, he was speechless.

Eventually, Hewett’s radical passion is spent, disillusioned in part by the collapse of the savings scheme run by his workmen’s club, for radicals – Gissing suggests – are no more honest than those they disparage.

For all the sense of hopelessness, Gissing was able to find the ‘evening sunlight to close’ that he had spoken of to Thomas Hardy. At the end of the novel, Sidney Kirkwood and Jane Snowdon meet at the grave of her grandfather.

In each life little for congratulation. … Yet to both their work was given. Unmarked, unencouraged save by their love of uprightness and mercy, they stood by the side of those more hapless, brought some comfort to hearts les courageous than their own. Where they abode it was not all dark. Sorrow certainly awaited them, perchance defeat in even the humble aims that they had set themselves; but at least their lives would remain a protest against those brute forces of society which fill with wreck the abysses of the nether world.

Simply surviving uncorrupted amid the brutalism and misery constituted a challenge to the social order that tolerated such injustice. And telling the story of the nether world helped Gissing gain some closure on years of personal misery. His biographer, Paul Delany, argues that in the process of writing the novel, ‘Gissing paid off his debt to Nell’s memory, and decided that he need no longer walk the streets of outcast London’. He went on to write many successful London novels, among them New Grub Street and The Odd Women, but never again chose to focus on the London poor.

The latter day ‘Nether World’

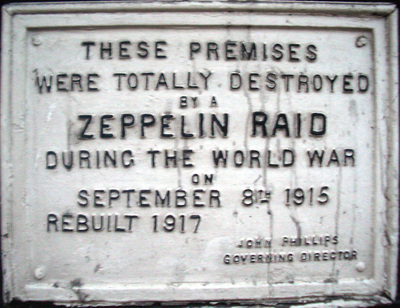

Clerkenwell was on the cusp of profound change as Gissing wrote about the area. The road buildings and slum clearances are captured in his pages, as are the new commuter services. Sidney Kirkwood ends the book travelling to work in Clerkenwell from an industrial cottage in Crouch End ‘on the northern limit’ of London, where the streets ‘have a smell of newness, of dampness’. Fronting the main thoroughfares, old and new, warehouses and light industrial buildings sprang up. The wars brought down more of the old buildings (a plaque on Farringdon Road marks premises ‘totally destroyed’ by a zeppelin raid in September 1915), and much of the housing that remained was swept away to make space for huge new municipal estates.

Clerkenwell was on the cusp of profound change as Gissing wrote about the area. The road buildings and slum clearances are captured in his pages, as are the new commuter services. Sidney Kirkwood ends the book travelling to work in Clerkenwell from an industrial cottage in Crouch End ‘on the northern limit’ of London, where the streets ‘have a smell of newness, of dampness’. Fronting the main thoroughfares, old and new, warehouses and light industrial buildings sprang up. The wars brought down more of the old buildings (a plaque on Farringdon Road marks premises ‘totally destroyed’ by a zeppelin raid in September 1915), and much of the housing that remained was swept away to make space for huge new municipal estates.

So much has gone, yet fragments of Gissing’s Clerkenwell remain. Hidden away on Albemarle Way, next to a gemstone merchants, Gleave & Co. ‘watch and clock materials’ is almost the last vestige of what was once the area’s defining trade. Nearby Clerkenwell Green remains something of a backwater, its character preserved by four defining buildings: the commanding Sessions House, once a court and now a conference centre, the refurbished Marx Memorial Library, the Crown Tavern, and looming over all, the bleached, rounded, elegant spire of St James’s. The Green’s old centrepiece, a pump, has gone, but it remains a public space – and now much more fashionable than in Gissing’s day.

So much has gone, yet fragments of Gissing’s Clerkenwell remain. Hidden away on Albemarle Way, next to a gemstone merchants, Gleave & Co. ‘watch and clock materials’ is almost the last vestige of what was once the area’s defining trade. Nearby Clerkenwell Green remains something of a backwater, its character preserved by four defining buildings: the commanding Sessions House, once a court and now a conference centre, the refurbished Marx Memorial Library, the Crown Tavern, and looming over all, the bleached, rounded, elegant spire of St James’s. The Green’s old centrepiece, a pump, has gone, but it remains a public space – and now much more fashionable than in Gissing’s day.

Off the Green, Clerkenwell Close follows its old serpentine path, graced by buildings with which Gissing would have been familiar. Pear Tree Court is the site of the Peabody Clerkenwell Estate, a step up perhaps from the ‘terrible barracks’ which so appalled Gissing, but of the same period and purpose. Pockets of stylish Victorian terraced housing survive in and around Sekforde Street. As recently as the 1980s, much of the area was down-at-heel, and the passer-by was occasionally assailed by fumes from metal plating workshops. South Clerkenwell is now fashionable, ‘a synonym for urban rejuvenation and energy’ in the rose-tinted judgement of the Survey of London, and reputed to have more architects and design studios to the acre than anywhere in Europe.

Search hard and, just occasionally, you can get still get a vicarious sense of labyrinthine early modern Clerkenwell: venturing through Jerusalem Passage, a narrow isthmus linking Clerkenwell Green to St John’s Square; navigating down Sutton Lane, a semi-concealed pathway which takes you not round but through a building; standing in the minuscule St. John’s churchyard alongside Mallory Buildings; in Hat and Mitre Court on the east side of St John’s Street; even more so, at Passing (‘Pissing’) Alley on the other side of the road, a forbidding passageway with sheer walls and sandstone flags.

Search hard and, just occasionally, you can get still get a vicarious sense of labyrinthine early modern Clerkenwell: venturing through Jerusalem Passage, a narrow isthmus linking Clerkenwell Green to St John’s Square; navigating down Sutton Lane, a semi-concealed pathway which takes you not round but through a building; standing in the minuscule St. John’s churchyard alongside Mallory Buildings; in Hat and Mitre Court on the east side of St John’s Street; even more so, at Passing (‘Pissing’) Alley on the other side of the road, a forbidding passageway with sheer walls and sandstone flags.

A little further towards Islington, the streets have more vitality, a more rooted community, than gentrified south Clerkenwell. On a sunny weekend afternoon, Spafields – once an even more insurrection-minded meeting place than Clerkenwell Green – has a touch of the cockney about it. Clarks on Exmouth Market – about as a traditional an eatery as you can find, ‘jellied eels £2.55, hot eels £2.75, eels and mash £4.10’- still sits its customers on pew-like benches, and serves its mash in scooped out spherical globules. ‘Hi Nan, you alright?!’, shouts a young man called Tel as he cycles past the open door – his gran is one of a triptych of elderly white women behind the serving counter.

Here too, the last vestiges of industrious Clerkenwell are increasingly at risk. Doors away is the much-in-demand Moro, ‘known for its award-winning Moorish cuisine’. Round the corner on Farringdon Road, the Quality Chop House ‘progressive working class caterer’ is the same style and vintage as Clarks, with similar high-backed wooden seats. Within my memory, you could read the communist Morning Star over a breakfast of bloaters. Then it went up market, with oysters topping the menu. Keeping on with the kippers might have been a better bet – the last time I walked past, the building was semi-derelict.

Further down towards the City, Farringdon Road gets a little louche. Not all that far from Gissing’s ‘terrible barracks’ – in a building he would have seen being constructed as he researched and wrote The Nether World – is the Chatterbox Topless Bar: ‘Drinks £10, No other charges, Hostesses wanted’. That would have given Gissing something to write about. – A.W.

Further down towards the City, Farringdon Road gets a little louche. Not all that far from Gissing’s ‘terrible barracks’ – in a building he would have seen being constructed as he researched and wrote The Nether World – is the Chatterbox Topless Bar: ‘Drinks £10, No other charges, Hostesses wanted’. That would have given Gissing something to write about. – A.W.

References

George Gissing – Workers in the Dawn (1880), The Unclassed (1884), Demos (1886), Thyrza (1887), The Nether World (1889)

Pierre Coustillas (ed), London and the Life of Literature in late-Victorian England: the diary of George Gissing, novelist, 1978

The Collected Letters of George Gissing, multi-volume, 1990 onwards

Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes, 1884-5

Rev William Dawson, A mid-London Parish: a short history of the parish of S. John’s, Clerkenwell, 1885

P.J. Keating, The working classes in Victorian fiction, 1971

John Goode’s introduction to the Harvester Press edition of The Nether World, 1974

John Halperin, Gissing: a life in books, 1987

Paul Delany, George Gissing: a life, 2008

Survey of London, vol. XLVI: South and East Clerkenwell, 2008

Alan Ainsworth, Clerkenwell: change and renewal, 2010

All rights to the text remain with the author.