Andrew Lane

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

I had neither kith nor kin in England, and was therefore as free as air — or as free as an income of eleven shillings and sixpence a day will permit a man to be. Under such circumstances, I naturally gravitated to London, that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained. There I stayed for some time at a private hotel in the Strand, leading a comfortless, meaningless existence, and spending such money as I had, considerably more freely than I ought.

These are the words that Arthur Conan Doyle uses at the start of his novel A Study in Scarlet to introduce us to narrator Dr John Watson, and to set the scene for Watson’s later meeting with the eccentric consulting detective Sherlock Holmes. A Study in Scarlet was published in 1887, and is set somewhere between 1881 and 1885 (more on the author’s offhand approach to dates in a moment). Conan Doyle went on to write three more novels and fifty-six short stories using Sherlock Holmes as the central character. The last-written story (‘The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place’) was published in 1927 but set much earlier. The last chronological story (‘His Last Bow’) was published in 1917, but set in 1914.

In Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle created one of the best known and longest lasting characters in English fiction. The Sherlock Holmes stories have justifiably never been out of print, and rather than languishing on the shelves designated for ‘classic literature’ they sit proudly in the ‘Crime’ section of bookshops and libraries, alongside the latest (usually Scandinavian) authors. As well as having been adapted into too many films, TV programmes, comics and computer games in too many countries to count, they have also given rise to a whole industry of literary pastiches and parodies. Conan Doyle did this by accident – he never set out to make a lasting impact with Sherlock Holmes (in later life he thought that his historical novels would be his legacy to the literary world). His secrets were firstly a writing style that, paradoxically, had no style – it spoke directly to the reader, without artifice – and secondly an extraordinary central character who was superficially unlovable except through the filtering eyes of his friend and biographer, John Watson.

In Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle created one of the best known and longest lasting characters in English fiction. The Sherlock Holmes stories have justifiably never been out of print, and rather than languishing on the shelves designated for ‘classic literature’ they sit proudly in the ‘Crime’ section of bookshops and libraries, alongside the latest (usually Scandinavian) authors. As well as having been adapted into too many films, TV programmes, comics and computer games in too many countries to count, they have also given rise to a whole industry of literary pastiches and parodies. Conan Doyle did this by accident – he never set out to make a lasting impact with Sherlock Holmes (in later life he thought that his historical novels would be his legacy to the literary world). His secrets were firstly a writing style that, paradoxically, had no style – it spoke directly to the reader, without artifice – and secondly an extraordinary central character who was superficially unlovable except through the filtering eyes of his friend and biographer, John Watson.

To counterbalance his extraordinary literary achievements, Conan Doyle has come in for a great deal of criticism over the years for, amongst other things, his slapdash approach to continuity. Dr Watson’s wound, for instance, received during military service in Afghanistan, moves mysteriously from leg to shoulder and back, and his first name varies between John and James, while the faithful housekeeper and landlady Mrs Hudson becomes Mrs Turner on one occasion. He has also been criticised for his cavalier approach to time – The Sign of Four itself takes place in both July and September, according to the text, and the only way to rationalise the various appearances and mentions of Holmes’s nemesis Professor James Moriarty on the dates that the stories are supposedly set is to assume that the evil Professor has two brothers, and that all three siblings are named James.

What he has not been criticised to any great extent is his description of London, which is where the majority of the stories are at least partially set. Quite the opposite – it’s probably fair to say that Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories have heavily coloured people’s image of Victorian London, but is this fair? His initial characterisation of that city as a ‘great cesspool’ full of ‘idlers and scroungers’, for instance, indicates to the casual reader that Conan Doyle will be placing the stories against a richly detailed Dickensian background of slums, sordid taverns and grotesque inhabitants, but this promise is never satisfied. Anybody looking to Conan Doyle for a contemporaneous critique of social conditions in the great metropolis will have to look elsewhere.

A quick look at Conan Doyle’s biography will indicate why this is the case. He was born in Edinburgh and educated first in Lancashire and then, briefly, in Austria. He returned to Edinburgh to study medicine and, having qualified, was initially employed as a ship’s surgeon on a voyage to West Africa. On arrival back in England he set up in practice first in Plymouth and then in Portsmouth, which is where he wrote A Study in Scarlet. The location absent in all of that peripatetic existence is London. Admittedly he visited the city before finally moving there in 1891 (he had a notable dinner at the Langham Hotel in London in 1889) but these would have been fleeting visits, not enough to soak up the rich atmosphere and to explore the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) differences in social class that could (and still can) exist between streets only a few minutes’ walk from one another.

The irony is that Conan Doyle’s writings have produced a vivid picture in people’s minds of what Victorian London was like. The vision is of thick fog, clattering hansom cabs, gas-lit streets, taverns resounding with Cockney sing-songs, pavements cluttered with beggars and ragged urchins, and telegrams arriving at all hours of the day and night containing vital facts. This picture is, however, largely an invention. It is based firstly on an extrapolation of just a handful of comments in the stories and secondly on the imaginations of several generations of film and TV producers who have interpreted the stories and converged on a convenient shorthand representation. Consider the fact that Holmes’s recorded career covers some thirty-four years between the earliest and latest chronological stories. In that time gas lamps were replaced with electric lighting, hansom cabs were replaced with cars and telegrams were replaced with telephones. Mention the name “Sherlock Holmes”, however, and it can be guaranteed that people will not be thinking about electric lights, cars and telephones. Fog, hansoms and gaslights are, and forever will be, the first things that come to mind.

Of the four Sherlock Holmes novels written by Conan Doyle, both A Study in Scarlet and The Valley of Fear use Holmes as a “wrap-around” for a flashback story set in America, and The Hound of the Baskervilles takes place largely (and famously) on Dartmoor. Only his second Holmes novel The Sign of Four (or The Sign of the Four, as it was originally titled), takes place in numerous London locations – but the book was first published in 1890, the year before Conan Doyle relocated to London from Portsmouth, and it shows.

Of the four Sherlock Holmes novels written by Conan Doyle, both A Study in Scarlet and The Valley of Fear use Holmes as a “wrap-around” for a flashback story set in America, and The Hound of the Baskervilles takes place largely (and famously) on Dartmoor. Only his second Holmes novel The Sign of Four (or The Sign of the Four, as it was originally titled), takes place in numerous London locations – but the book was first published in 1890, the year before Conan Doyle relocated to London from Portsmouth, and it shows.

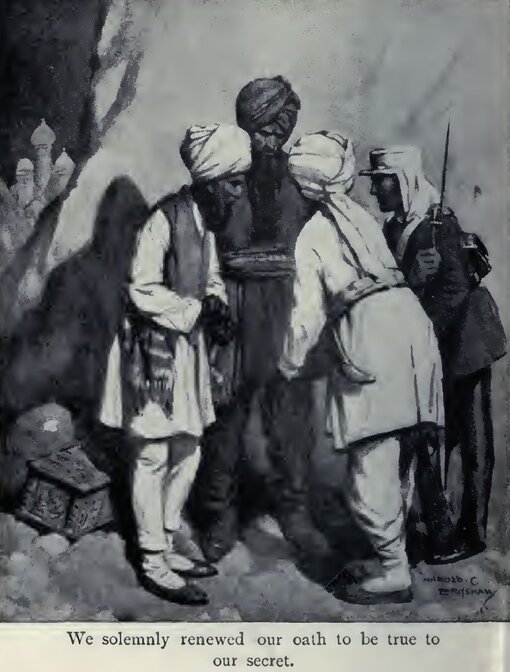

The plot of The Sign of Four is relatively direct for a book that is supposed to be a mystery. Holmes and Watson are whiling away the time at their residence in Baker Street when a visitor arrives. It is a Miss Mary Morstan, and she tells them a story about the disappearance of her father and the mysterious arrival once a year of a parcel addressed to her containing a pearl. Now a letter has arrived from the same source asking her for a meeting, and she wants Holmes and Watson to accompany her. The three of them travel to a house in Brixton, south London, where they meet Thaddeus Sholto. He tells them that his father, Major John Sholto, had been sending her the pearls. The reason was that John Sholto and Mary Morstan’s father were stationed together in India and came into possession of a treasure chest of jewels. The two men had argued, back in England, and Mary Morstan’s father had suffered a heart attack, which Sholto then covered up by hiding the body. Since that date he had been sending Mary the pearls as a kind of apology, but Sholto himself has now died. For months Thaddeus and his brother, Bartholomew, have been searching their father’s house for the treasure, and now Bartholomew has sent word that he has found it.

The four of them travel the short distance to Upper Norwood, where brother Bartholomew is still living in their father’s house. Bartholomew is dead, however – pricked by a poisoned thorn – and the jewels are missing. Holmes and Watson follow the killers, but eventually lose the trail at the edge of the Thames.

Holmes sets out by himself to investigate, and determines that the killers are using a steam launch to travel on the Thames. He alerts Watson and the police, and together they try to catch the steam launch with their own steam-powered police boat. A chase ensues down the Thames during which one of the killers (a midget Andaman islander) drowns and the other (a one-legged sailor named Jonathan Small) is rescued.

In a descriptive account that echoes those in A Study in Scarlet and The Valley of Fear, Small tells his questioners the story of how he and three confederates came into possession of the treasure, how Sholto and Morstan took it from them, and how he has spent years searching the world for it.

Setting aside the plot, the detective work, the characterisation and the historical backdrop, it’s instructive to examine how The Sign of Four treats the city in which most of its action takes place. Promisingly, the book starts off with an atmospheric and yet rather generic description of London as seen through the filter of the kind of unpleasant autumn day with which most people will be familiar:

Setting aside the plot, the detective work, the characterisation and the historical backdrop, it’s instructive to examine how The Sign of Four treats the city in which most of its action takes place. Promisingly, the book starts off with an atmospheric and yet rather generic description of London as seen through the filter of the kind of unpleasant autumn day with which most people will be familiar:

It was a September evening and not yet seven o’clock, but the day had been a dreary one, and a dense drizzly fog lay low upon the great city. Mud-coloured clouds drooped sadly over the muddy streets. Down the Strand the lamps were but misty splotches of diffused light which threw a feeble circular glimmer upon the slimy pavement. The yellow glare from the shop-windows streamed out into the steamy, vaporous air and threw a murky, shifting radiance across the crowded thoroughfare. There was, to my mind, something eerie and ghostlike in the endless procession of faces which flitted across these narrow bars of light—sad faces and glad, haggard and merry. Like all humankind, they flitted from the gloom into the light and so back into the gloom once more.

This is Watson describing London, but it might just as easily have been Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow or Edinburgh.

During the course of the book, Holmes and Watson seem to be perpetually rushing from one London location to another; sometimes together, sometimes apart, and occasionally accompanied by Miss Mary Morstan, Inspector Athelney Jones and a dog named Toby. They start in Baker Street, at number 221b. This has become a world-famous address since publication of A Study in Scarlet, but it doesn’t take the casual investigator long to discover that the address itself was and is completely fictitious. Baker Street at the time that The Sign of Four is set was considerably shorter than it is today, running only from Portman Square in the south to the junction with Crawford Street and Paddington Street. From there up to Marylebone Road it was called York Place. North of Marylebone Road it was Baker Street again, but this time Upper Baker Street (a distinction never mentioned by Conan Doyle). The numbering is as problematic as the street name: the Baker Street numbers only ran from 1 to 84 at the time, so there never was a 221 Baker Street, let alone a 221b. And while we are on the subject, what exactly did that b mean? The basement flat? A flat above a shop or an office? Neither possibility was ever mentioned by Watson in the entire Conan Doyle canon.

Watson does tell us, at various points in the stories, that 221b Baker Street had a bow window in their first floor sitting room, and that the house backed on to a mews. This hardly helps us track it down: no upstairs room in Baker Street ever had a bow window, and there were no mews at the back. Don’t look to Conan Doyle for accuracy.

From Baker Street our intrepid heroes travel by cab to the Lyceum Theatre. In the hands of another writer we might get a detailed description of the theatre and the theatre-going public, but Conan Doyle is more concerned with the actions of his characters and the dialogue between them. At the time the book was set the Savoy Theatre, not too far away, was lit by electricity, which in the hands of an author nowadays writing about the 1880s would form an interesting diversion, but no, not here.

From the Lyceum our characters are taken on a cab ride to parts unknown. It is foggy outside, and Holmes narrates the journey for us:

“Rochester Row,” said he. “Now Vincent Square. Now we come out on the Vauxhall Bridge Road. We are making for the Surrey side apparently. Yes, I thought so. Now we are on the bridge. You can catch glimpses of the river.”

We did indeed get a fleeting view of a stretch of the Thames, with the lamps shining upon the broad, silent water; but our cab dashed on and was soon involved in a labyrinth of streets upon the other side.

“Wordsworth Road,” said my companion. “Priory Road. Lark Hall Lane. Stockwell Place. Robert Street. Cold Harbour Lane. Our quest does not appear to take us to very fashionable regions.”

This is nothing more than a list of street names. One can imagine Conan Doyle sitting at his desk in Southsea, Portsmouth, consulting a gazetteer of London as he wrote.

The journey ends shortly afterwards in Brixton (assuming, of course, that Conan Doyle meant Coldharbour Lane rather than Cold Harbour Lane). Conan Doyle describes the area with economy and precision:

The journey ends shortly afterwards in Brixton (assuming, of course, that Conan Doyle meant Coldharbour Lane rather than Cold Harbour Lane). Conan Doyle describes the area with economy and precision:

We had indeed reached a questionable and forbidding neighbourhood. Long lines of dull brick houses were only relieved by the coarse glare and tawdry brilliancy of public-houses at the corner. Then came rows of two-storied villas, each with a fronting of miniature garden, and then again interminable lines of new, staring brick buildings—the monster tentacles which the giant city was throwing out into the country.

It is interesting to note that in those days Brixton counted as the edges of the countryside. One would have to travel many more miles these days before seeing a green field.

Following a brief interlude in a ‘third-rate suburban dwelling house’, our heroes head for nearby Upper Norwood. There they arrive at a very different place of habitation – the opulent Pondicherry Lodge, which stands by itself in an expanse of garden (which has itself been heavily dug up by the Sholto brothers in search of the treasure). The suggestion – and it is no more than that – is that Upper Norwood is, in this year, a very countrified area, and the houses are all isolated from one another. That is certainly not the case now.

Watson takes Miss Morstan back to her lodgings in Camberwell, also conveniently located that side of the river, and then heads to Lambeth to fetch a tracker dog for Holmes to use. With Toby the dog leading, the two men follow the scent trail of the killers of Major John Sholto:

We had during this time been following the guidance of Toby down the half-rural villa-lined roads which lead to the metropolis. Now, however, we were beginning to come among continuous streets, where labourers and dockmen were already astir, and slatternly women were taking down shutters and brushing door-steps. At the square-topped corner public-houses business was just beginning, and rough-looking men were emerging, rubbing their sleeves across their beards after their morning wet…

We had traversed Streatham, Brixton, Camberwell, and now found ourselves in Kennington Lane, having borne away through the side streets to the east of the Oval. The men whom we pursued seemed to have taken a curiously zigzag road, with the idea probably of escaping observation. They had never kept to the main road if a parallel side street would serve their turn. At the foot of Kennington Lane they had edged away to the left through Bond Street and Miles Street. Where the latter street turns into Knight’s Place, Toby ceased to advance …

Again, we find ourselves a victim of Conan Doyle’s London gazetteer and his wandering finger. A contemporary author writing of a foot-slog through South London would indulge in a great deal more description of the houses, the shops, the people and the various sights that were experienced on the way. Not here, alas.

Our course now ran down Nine Elms until we came to Broderick and Nelson’s large timber-yard just past the White Eagle tavern…

It tended down towards the riverside, running through Belmont Place and Prince’s Street. At the end of Broad Street it ran right down to the water’s edge, where there was a small wooden wharf.

Holmes and Watson end up on the South side of Thames, opposite Millbank. They then head back to the mythical 221b Baker Street, with mentions of Greenwich and Gravesend being made. Watson makes two trips to Camberwell (he is now courting Mary Morstan), and Holmes goes wandering off by himself in disguise. When he returns, he tells Watson that he has tracked their quarry to a boat yard near the Tower of London. The two of them join a Scotland Yard detective (not, alas, Inspector Lestrade) at Westminster Pier and pursue the killers of Bartholomew East along the Thames from the Tower all the way down to Plumstead, where the final confrontation is played out and the treasure is dumped into the murky waters.

That final section, with the police steam boat desperately trying to overtake the villains’ steam boat, and with the murderous Andaman islander shooting poison darts at our heroes, is amongst the most thrilling in the entire canon of English literature. It is, alas, far too short, and it still tells us nothing of the historical Thames, which has been the backbone of London since before there was a London. Like everything else geographical in the book, it is a convenient and thinly sketched out backdrop. If the book had been set in Liverpool and the final chase had occurred on the River Mersey, or the book had been set in Newcastle and the final chase had occurred on the River Tyne, then virtually no words would need to be changed. And 221b Baker Street would be equally as realistic as an address.

That final section, with the police steam boat desperately trying to overtake the villains’ steam boat, and with the murderous Andaman islander shooting poison darts at our heroes, is amongst the most thrilling in the entire canon of English literature. It is, alas, far too short, and it still tells us nothing of the historical Thames, which has been the backbone of London since before there was a London. Like everything else geographical in the book, it is a convenient and thinly sketched out backdrop. If the book had been set in Liverpool and the final chase had occurred on the River Mersey, or the book had been set in Newcastle and the final chase had occurred on the River Tyne, then virtually no words would need to be changed. And 221b Baker Street would be equally as realistic as an address.

It has been said that you can read all of Jane Austen books without realising that the Napoleonic wars were going on in the background. In the same way, you can read all fifty-six short stories and four novels that Arthur Conan Doyle wrote about Sherlock Holmes without finding out much about the London of the time. For instance, Conan Doyle does mention various types of transport used by Holmes and Watson – hansoms, four wheelers, jarveys, and even the horse-drawn buses that plied set routes – but he never describes the piles of manure that must have been left by those horses, or the sheer stench that must have been the result. And he almost never tells us about the Underground trains. The first underground line – the Metropolitan – opened in 1863, about twenty years before Holmes and Watson met, but there are very few mentions in the stories, and no descriptions at all. Similarly, the first telephone exchange opened in London in Lombard Street in 1879, and a contemporary account from 1882 mentioned an employee giving notice by telephone which means that they must have had quite a degree of “market penetration” as it is known, but there is no mention of a telephone in 221b Baker St until sixteen years later (although Conan Doyle does have Holmes crossing the road to use the telephone in the Post Office in 1888). Conan Doyle tells us that when Watson first arrived in London he was living on eleven shillings and six pence a day, but he never puts this in context. In those days a man could live in a hotel in Central London for less than two pounds a week – including breakfast and dinner. A bottle of Bass beer cost three pence; less for a bottle of Guinness. A First Class return to Paris cost £2 12s and 6d. And in a wider social context, Scotland Yard detectives such as Lestrade, Gregson, MacDonald and so on get regular mentions in the canon but there is no hint of police corruption, ignoring the fact that in 1878 fully three out of the four Chief Inspectors of London’s Detective Branch were found guilty of corruption. This led directly to the formation of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), which the humorous magazine Punch subsequently referred to as the Defective Department.

Much of the above could be taken to be a critique of Conan Doyle as a writer. It is not meant that way – his achievements far outweigh any shortcomings in his prodigious output. It is rather a reminder that while Conan Doyle was trying to accomplish many things with his Sherlock Holmes stories, writing about London was not one of them.

Andrew Lane is a novelist and also the author of several works of non-fiction looking at the world of films and TV programmes. He has written a series of novels about the early years of Sherlock Holmes.

Further Reading

Michael Harrison, The London of Sherlock Holmes, David & Charles, 1972

H.R.F.Keating, Sherlock Holmes – The Man and His World, Thames and Hudson, 1979

Pondicherry Lodge

Pondicherry Lodge is the most memorable of the many London locations in The Sign of Four – a suitable name for the retirement home of an old India hand such as Major Sholto. Conan Doyle locates the house in Upper Norwood – a building which ‘stood in its own grounds, and was girt round with a very high stone wall topped with broken glass. A single narrow iron-clamped door formed the only means of entrance’. Once through that door, ‘a gravel path wound through desolate grounds to a huge clump of a house, square and prosaic, all plunged in shadow save where a moonbeam struck one corner and glimmered in a garret window. The vast size of the building, with its gloom and its deathly silence, struck a chill to the heart.’

Conan Doyle knew Norwood well. He lived there for three years and was keenly involved in the local cricket club and in the Upper Norwood Literary and Scientific Society (as I discover from Alistair Duncan’s The Norwood Author: Arthur Conan Doyle and the Norwood years). But he moved there in the year after The Sign of Four was published, and there’s nothing to indicate that he was familiar with the locality at the time he devised the Sholtos’ forbidding family home.

That hasn’t prevented two very different schools of research prising into the meaning of Pondicherry Lodge. Students of colonial and post-colonial literature have explored the novel’s engagement with India and Indians – indeed one writer has commented on the Lodge’s ‘orientalist character both inside and out’ and mused about the meaning of its transnational name (Pondicherry was a French enclave in southern India) so choosing to overlook the possibility that Conan Doyle was attracted simply by the resonance and rhythm of the word.

The remarkably assiduous body of Sherlockians have taken on the more daunting task of locating an (please forgive the heresy) imagined Lodge. Not so much the building that Conan Doyle had in mind as the model for Pondicherry Lodge, but the one that he should have had in mind – the house that most approximates to the fictional version.

Holmes enthusiasts are now generally agreed that Kilravock House on Ross Road in Upper Norwood, built as the retirement home of one Major Thomas Ross, is the best fit. It stands close to the brow of quite a steep hill – a huge, squat (‘clump’ was Conan Doyle’s word) mid-nineteenth century mansion, now divided into thirteen flats, with a commanding southerly outlook over the Crystal Palace football stadium and far beyond.

The spot has a slightly out-of-the-way feel. Across the road is the cosy but somewhat neglected Grangewood Park – its bandstand, museum and café all long since swept away.

On a spring afternoon, squawking ring-necked parakeets flit around the park, flashing their bright green plumage – not as menacing as an Andaman islander with a blow dart but an enduring touch of the sub-continent none-the-less. - AW

All rights to the text remain with the author.