Eliza Cubitt

I have been told by certain friendly advisers that this story is impossible. I have, therefore, stated the fact on the title-page, so that no one may complain of being taken in or deceived. But I have never been able to understand why it is impossible.

Besant’s preface to the first edition, 1882

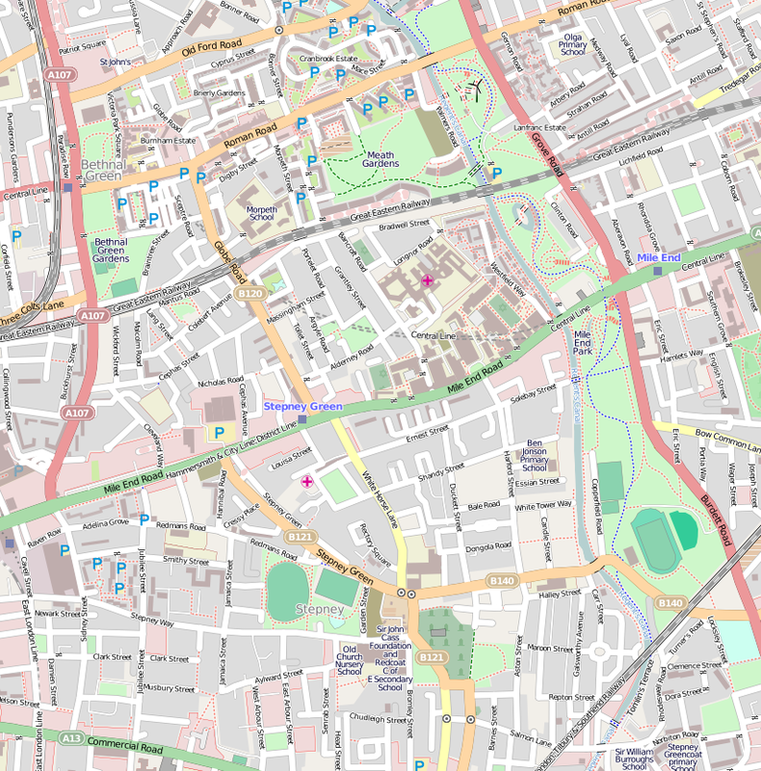

Few of the numerous late-nineteenth century novels concerned with the East End had such a tangible impact as Walter Besant’s All Sorts and Conditions of Men (1882). In this novel, two young philanthropists of private means exert themselves to deal with what they see as the great problem facing East Enders in the 1880s – the lack of both ambition and amusement. The young people devise an incredible – or, as Besant later called it, ‘impossible’ scheme for the improvement of the East End – a ‘Palace of Delight’, to be built at Stepney Green, which would provide evening classes, lectures, leisure and sporting facilities as well as music and art.

Such projects were not previously unheard of. Prince Albert’s Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition in 1851, inspired similar public buildings for education and entertainment. The novel aided in dispelling the cynicism of fin de siècle attitudes towards these institutions. In Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, for example, Lord Harry states that these projects don’t work because poverty ‘is the problem of slavery, and we try to solve it by amusing the slaves.’ All Sorts and Conditions of Men inspired the trustees of The Beaumont Trust, (with money left from philanthropist John Barber Beaumont) to aid in the development of just such an institution as the novel describes, and in 1886 the building of the People’s Palace was begun at Mile End. The standard of teaching at the evening classes developed to such an extent that by the late 1890s, the University of London awarded BSc degrees there, and in 1907 the Palace became part of UoL on a trial basis under the title of East London College. Besant’s story, then, proved more than possible – it inspired a college more successful than even he could have imagined.

The novel concerns Angela Messenger, heiress to thirteen acres of brewery and houses in the East End, and Harry Goslett, who discovers himself to be the nephew of Uncle Bunker, one of the chief clerks in the Messenger brewery, and not the nephew of his adoptive uncle, Lord Jocelyn. These upper-class changelings seek to transform their lives, and if possible, the East End itself, by undertaking ‘voluntary descent and eclipse’, inveigling themselves in its darkest reaches. In doing so they experience a sort of alternative finishing school, an exploration of another life. The East End was, to the upper classes of the West End, thought of and often presented as a foreign land, almost unreachable:

Two millions of people, or thereabouts, live in the East End of London. That seems a good-sized population for an utterly unknown town. They have no institutions of their own to speak of, no public buildings of any importance, no municipality, no gentry, no carriages, no soldiers, no picture-galleries, no theatres, no opera – they have nothing. It is the fashion to believe that they are all paupers, which is a foolish and mischievous belief, as we shall presently see. Probably there is no such spectacle in the whole world as that of this immense, neglected forgotten great city of East London. It is even neglected by its own citizens, who have never yet perceived their abandoned condition. They are Londoners, it is true, but they have no part or share of London. (…) If anything happens in the East, people at the other end have to stop and think before they can remember where the place may be.

Angela, educated at Newnham College, Cambridge, does not wish to pursue her studies as her friend Constance does. Indeed, studying has proven detrimental to Constance’s appearance – she ‘wore spectacles and looked older than she was, by reason of too much pondering over books and perhaps too little exercise.’ Rather, Angela, disillusioned with political economy, will apply practical solutions to the problem of poverty: ‘I know all the theories about people, and I don’t believe any of them will work. Therefore, my dear, I shall get to know the people before I apply them.’ Her inheritance, she feels, earned by her grandfather, a Whitechapel man, confers a duty upon her – she ought to be ‘part of this striving, eager, anxious humanity’. She tells Constance; ‘I belong to the People, with a great big P, my dear – I cannot bear to go on living by their toil and giving nothing in return.’ She therefore decides to lose herself in the unknown, unknowable East – ‘I efface myself. I vanish. I disappear.’ Harry has the rather different position of having grown up as his adoptive uncle Jocelyn’s experiment. Jocelyn undertook to adopt the orphaned Harry, to “educate him in all that a gentleman can learn, and then (…) send him back to his friends, whom he would make discontented, and so open the way for civilisation.” Harry and Angela succeed in crossing the ‘great gulf fixed’ between the East and West End.

Harry and Angela find themselves at a lodging house in Stepney Green, that ‘small strip of Eden’, wherein a variety of eccentric characters lodge with Mrs Bormalack. The two immediately arouse suspicion, Angela for her innately ladylike behaviour, Harry for his indolence and ‘peculiarities’ of manner and speech. Undertaking the disguises of dressmaker and cabinet maker, the two discuss the richest heiress in England – Angela – and Harry suggests that the greatest way for Miss Messenger to help the East End, without pauperising its people, would be to set up a number of schools after the great private school model, and a Palace of Delight, which would be a centre for arts and culture for adults. As they develop this scheme, under the guise of writing to the heiress with their ideas for the area, Angela begins her co-operative dressmakers’ ostensibly supplied by Miss Messenger from a distance, and run by Angela as Miss Kennedy.

While Harry and Angela ‘keep company’, they discover the romance of the area. In the East End, Angela is inspired by her surroundings; as she tells Harry: ‘I am always getting a new sensation’. There is romance in the unique Stepney sunsets – and eventually a romance blossoms between the two interlopers too:

If one comes to think of it, this was rather a remarkable result of a descent into the Lower Regions. One expects to meet in the Home of Dull Ugliness things repellent, coarse, enjoying the freedom of Nature, unrestrained, unconventional. Harry found, on the contrary, the sweetness of Eden, a fair garden of delights, in which sat a peerless lady, the Queen of Beauty, a very Venus.

So thinks Harry, whilst lamenting the fact that his love is a dressmaker, and wondering whether he ought to ‘go back to Piccadilly, and there forget her. Yet he remained, every day he sought her again…’

Angela and Harry do not perceive the East End with unqualified hopefulness. Indeed Angela remains for some time convinced that were her true wealth and position known; ‘most of them would try to borrow or steal from me.’ Later in the novel, Harry identifies a future problem of such institutions as he and Angela are planning, which bears similarities to Arthur Morrison’s criticisms of institutions in A Child of the Jago and ‘A Street’ in Tales of Mean Streets. Whilst walking in Victoria Park, the couple realise that they are surrounded by ‘the better sort’ because, as Harry says, ‘of course, when you open a garden of this sort for the people, the well-dressed come, and the ragged stay away and hide. There is plenty of ragged stuff round and about us, but it hides.’ Similarly in A Child of the Jago, Morrison portrays the irony that when Dicky Perrott the ragged child finds his way into an institute, he is invisible to the philanthropists, trustees, and ‘better sort’ of young clerks and engineers who go there to be ‘elevated’.

The East End proves a place of opportunity for Angela, as it was for many other young upper class ladies of this time. She relishes the chance to work there as she may act unfettered by the demands of high society. Indeed, as the author notes, the women’s movement is flourishing in the East End at this time, but the author has more sympathy for Angela’s lady-like, Christian behaviour than for this emergent emancipation:

Does it ever occur to the ‘better class’ that the work of women’s emancipation is advancing in certain circles with rapid strides? That is so, nevertheless; and large, if not pleasant, results may be expected in a few years therefrom.

Angela’s feminine influence on her surroundings, through improvements such as the planting of trees on Whitechapel Road, and the management and respectable amusement of her girls at the co-operative is so great that Harry makes the rather absurd claim that, ‘six months ago, no one laughed in Stepney at all.’

Angela and Harry dedicate their lives to each other and to the East End, and devote themselves to the management of the Palace of Delight. They succeed in establishing a place that will transform not only the East End but also the way the East End is understood and treated by the West End. The Palace of Delight is:

…a superior Aquarium, a glorified Crystal Palace, in which all the shows are open, all the performers are drilled and trained amateurs, and all the work actually is done for nothing: in which the management is by the people themselves, who will have no interference from priest or parson, rector or curate, philanthropist or agitator; and no patronage from societies, well-intentioned young ladies, meddling benevolent persons and officious promoters, starters, and shovers-along, with half an eye fixed on heaven and a half on their own advancement.

The solution to inequality between East and West London, Besant and Harry controversially suggest, is not for East Enders to gain power in Westminster, but to become more cut off, more separate from the society which has no place for them:

…having found that neither Conservatives, nor Liberals, nor Radicals, have ever been, or are ever likely to be, prepared with any real measure which should in the least concern themselves and their own wants, (…) the working men of this country hereby form themselves into a General League or Union, which shall have no other object than the study of their own rights and interests.

Harry suggests that emancipation will come only if East Enders recreate East London as a simpler, happier mirror of the West. This seems startling given that in the establishment of the People’s Palace, Lord Rosebery, a Liberal who later became Prime Minister, insisted that the institution should prevent the separation of East from West, and should ‘prove the sympathy of the West-end for the East-end.’ (Lord Rosebery, quoted from a meeting at the Drapers’ Hall, convened by the Beaumont Trustees, 19 April 1887 )

Sir Walter Besant

Walter Besant was born in 1836 in Portsmouth, Hampshire. He was the fifth of ten children in a middle class family. In his Autobiography he described his parents as clever, studious people: there were plenty of books in the house, at a time when ‘very few middle class people … had any books to speak of’. He was educated at Stockwell Grammar School and then King’s College London, where he began ‘to form definite ambitions’ with regard to writing. He studied at Christ’s College Cambridge, graduating in 1859. He then taught mathematics for a number of years before resigning to write fiction.

Besant was instrumental in setting up the Society of Authors to protect writers from exploitation by publishers and booksellers. This society, as Peter Keating notes, was often known as ‘Besant’s Society’ due to his intent involvement in its objectives and management. He served as the society’s chairman from 1884-1893.

As well as fiction – of which his own favourite was the historical novel Dorothy Forster – Besant wrote prolifically on London and its history. Besant’s 1886 novel, Children of Gibeon, was also set in London, focusing on a Hoxton parish. He described this book as ‘the most truthful of anything I have ever written.’ As in All Sorts and Conditions of Men, Besant was inspired by a comprehensive personal knowledge of the locality. He later said ‘I knew every street in Hoxton.’ Children of Gibeon and All Sorts and Conditions of Men were filmed in 1920 and 1921 respectively. Like his ‘Palace Journal’ colleague Arthur Morrison, Besant was a freemason, having been initiated in 1862. In 1874, he married Mary Forster-Barham, whom he discovered to be distantly related to the Dorothy Forster he later fictionalised in his favourite novel. Besant was knighted in 1895, and died in 1901 in London after a brief illness.

Stepney Green, Whitechapel, and the ‘Palace of Delight’ Today

In his autobiography, he laments that; ‘Unfortunately a polytechnic was tacked on to [the Palace]; the original idea of a place of recreation was mixed up with a place of education.’ However, this became the only enduring aspect of the People’s Palace.

The college later became Queen Mary College, which in 1934 became a college of the University of London. Now known as Queen Mary and Westfield College, the college has been invited to join the prestigious Russell Group of universities from August 2012.

Besant’s philanthropic imperative is continued by the work of People’s Palace Projects, based at Queen Mary University, who aim to use the arts to inspire positive social change and social equality.

As Besant later wrote in his autobiography, ‘Sir Edmund Currie, trying to create such a place, used the book as a text-book. The Palace was built. It was opened in 1887.’ The building was designed by E.R. Robson, an architect of the London School Board, and it was built not at Stepney Green, but at the east end of Mile End Road.

Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone for the East London Technical College at the opening ceremony. Due to lack of funds, a City firm, the Draper’s Company, was introduced in 1890 and funded the building of the technical college. Besant disapproved of the changes to his vision wrought by the Drapers’ Company, which emphasised the importance of education above amusement.

Further Reading

Fiction:

Besant, Walter, All in a Garden Fair (1883), Children of Gibeon (1886), Dorothy Forster (1884), The Alabaster Box (1900)

(Many of these are now out of print, but can be accessed for free online at archive.org or Project Gutenberg)

Mrs Humphry Ward, Marcella edited by Beth Sutton-Ramspeck and Nicole B. Meller (Ontario: Broadview Press Ltd., 2002)

Meade, L. T., A Princess of the Gutter (Wells Gardner, Darton & Company, 1895)

Non-Fiction:

Besant, Walter, Autobiography of Sir Walter Besant with a prefatory note by S. Squire Sprigge (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1902), London (1892), East London (1901), London in the Nineteenth Century (1909)

Keating, Peter, The Haunted Study: A Social History of the English Novel 1875-1914 (London: Fontana Press, 1991)

Koven, Seth, Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London (Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2004)

Joyce, S., ‘Castles in the Air: The People’s Palace, Cultural Reformism, and the East End Working Class’, Victorian Studies, 39/4 (1996), 513-38

Porter, Roy, London: A Social History (London: Penguin, 2000)

Ross, Ellen, editor, Slum Travelers: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860-1920 (University of California Press, 2007)

Weiner, Deborah E.B. ‘The People’s Palace: An image for East London in the 1880s’ in David Feldman and Gareth Stedman Jones, editors, Metropolis. London: Hsitories and Representations Since 1800 (London: Routledge, 1989)

Weinreb, Ben, and Christopher Hibbert, editors, The London Encyclopedia (London: Macmillan, 1983)

Useful Websites:

Queen Mary Library website has a gallery of images of the People’s Palace: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/library/

For more on the Trinity Almshouses, see Spitalfields Life Blog: https://spitalfieldslife.com/2011/04/20/a-renovation-at-trinity-green/

The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.. 2011. Encyclopedia.com. (April 16, 2012). http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-Besant-S.html

Besant’s obituary: Robert Williams Buchanan www.robertbuchanan.co.uk (the two writers died on the same day). Accessed 16th April 2012

All rights to the text remain with the author. All recent photos by Eliza Cubitt.