Reviewed by

Christopher Cook

Since his death in 1890 each generation has reinvented Vincent van Gogh in their own image, from the bold colourist who prefigured Modernism to the existential outsider of the second half of the twentieth century. So far not so bad at Tate Britain where curator Carol Jacobi follows this particular thread through a large, though perhaps over-inflated, exhibition: ‘Van Gogh and Britain’.

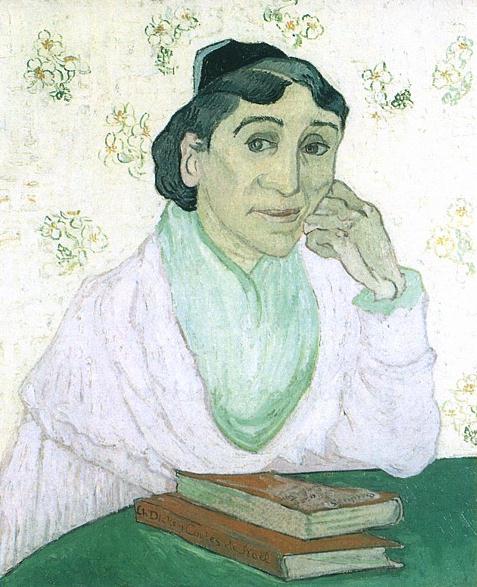

Jacobi’s narrative begins with the arresting portrait of L’Arlésienne from 1890 with two of Van Gogh’s favourite English books on Marie Ginoux’s table, Dickens’s Christmas Stories and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), followed by work by the English painters Van Gogh came to admire during his two years in London from 1873. We end – of course – with Francis Bacon’s reworking of The Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888), destroyed during the Second World War.

However, we really begin with a story about how and where Van Gogh found his style and subject matter and end with a clutch of British artists who very loosely may be said to have admired and to have learnt from him. Effectively this is two exhibitions in one and however hard the catalogue and the captions on the walls of each room attempt to paper over the crack, that judgement persists. It is not even banished by seeding so many crowd pleasers through show – L’Arlésienne and Sunflowers (1888) and Starry Night (1889), not to be looked at but snapped on mobile phones by a jostling throng hungry for their own ‘Vincent’.

This is perhaps where this exhibition’s journey could have begun: what makes Van Gogh so popular and why are his paintings so reproducible? Look at a reproduction of a Constable or a Turner, a Vermeer or even Hobbema’s The Avenue at Middelharnis (1689) – much admired by Van Gogh when he saw it at the National Gallery and borrowed for this show – and you know that however fine the colour printing may be it’s a copy. But pace Walter Benjamin and his celebrated 1935 essay Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Van Gogh’s Empty Chair or Sun Flowers framed and hung on a wall are somehow closer to the original. Art historian Griselda Pollock once baited a seminar at the National Gallery in London with the thought that Van Gogh’s popularity could be attributed to the perfecting of offset lithography printing at the time he was painting at this best. The bold black outlines, the brilliant and bold yellows of the sunflowers, the glaze on the pot were perfectly in tune with what this new printing technology could deliver.

Van Gogh was fascinated by the idea of mass reproduction, hence his collecting of prints by artists such as Luke Fildes and Frank Holl who made images for the new illustrated magazines of the late nineteenth century, the Graphic and the London Illustrated News. If artists such as Fildes, Herkomer, and Holl pictured London’s poor and dispossessed working class, then Gustave Doré, equally admired by Van Gogh, published a hell on earth in London: A Pilgrimage (1872). What all of them offered Van Gogh was a vision of what art could be: an art with a social conscience that could reach the widest audience.

As, early in this exhibition, you look at Holl’s print Flower Girl with its two men-about-town standing between the working girl with her blooming baskets and a pair of middle-class bonneted misses, or at Charles Reinhardt’s illustration for Dickens’s Hard Times (1854) with a seated Thomas Gradgrind, head in hands, you question whether their stylistic – as opposed to their thematic – influence on Van Gogh’s mature work was as strong and direct as this exhibition suggests. Yes, Van Gogh’s Worn Out (1881) borrows from the head-in-hands trope and the celebrated empty chair that stands for Gauguin follows a line that begins with Fildes’s celebrated print of Dickens’s empty chair, published after the writer’s death. But is the luminous Starry Night that rightly dominates one wall really the Thames transposed to Avignon, and is the influence here Whistler?

It is perhaps social ends more than artistic means that Van Gogh learnt from these English artists. His mature style is as much influenced by Japanese wood-block prints as British ‘black and whites’. After all it is Hokusai’s great wave that seems to have suggested the other starry night painted from his asylum room at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Yet the Japanese influence is a footnote at this Tate show.

For all the Japonaiserie there’s surely another thread to be teased out of Van Gogh’s English years. The catalogue that accompanies the exhibition reminds us that Van Gogh came to work in a London that was ‘the world capital of the graphic arts, fed by a thriving literary scene, industrial production methods and mass, international markets’. The gallery that Van Gogh worked for, Goupil & Co, specialised in art reproduction, and if that fed a young man’s imagination he also must have learnt here and later in Paris how the gallery system was transforming the production and consumption of art. In his letters to his brother Theo it is clear that Vincent understands how the art world worked. How does this impact upon his work?

What then of Van Gogh’s influence on English painting, the second exhibition, so to speak? Here the Tate excels itself, hanging works by Matthew Smith and the incomparable Samuel John Peploe from the early years of the twentieth century and then Christopher Wood and even David Bomberg in the same spaces as Van Gogh’s canvasses, particularly Sunflowers. Look at Peploe’s Tulips in a Pottery Vase (c. 1912) with the thick yellow impasto of the wall behind, the bold sun-like radiating brushstrokes, the burnished fruit on the tazza and the geometric zigzags of the table covering like a landscape. This is a Northern European yearning for ‘das Land, wo die Zitronen blühn’. There is something richly satisfying about seeing the work of artists who took their cue from Van Gogh, who understood that he changed the way in which we look at the natural world and at ordinary people. To put it bluntly, this is the better of the two-shows-in-one, but would it have brought the smartphone photographers in? Perish such a cynical thought.

Vincent van Gogh, L’Arlesienne (1890). Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Note on Contributor

Christopher Cook began his career in television, producing for BBC 2 and Channel 4. He has broadcast about the arts regularly on BBC Radios 3, 4, 5 and the BBC World Service. Christopher teaches ‘Cultural Studies’ for the Universities of Syracuse and Oregon on their London Programmes. He was Visiting Professor at the University of the Arts, London until 2013. He has been a visiting Gresham College Professor, a Visiting Research Fellow in the Theatre Department at Birkbeck College in the University of London at Queen Mary University. Christopher was the Director of the Cheltenham Festival of Literature in 2004 and was Chair of the Cheltenham International Music Festival until 2013.